The latest looks are in from the long and straight catwalks of Rome. Darlings, for too long we have contented ourselves with the same-old same-old. Celtic looks bereft of new ideas or new materials. All that is about to change: the Romans are on our shores and are here to stay. We are at the start of an exciting period, the conquest will revolutionise the look of Britain. Out with the old and in with the fabulous new!

The latest looks are in from the long and straight catwalks of Rome. Darlings, for too long we have contented ourselves with the same-old same-old. Celtic looks bereft of new ideas or new materials. All that is about to change: the Romans are on our shores and are here to stay. We are at the start of an exciting period, the conquest will revolutionise the look of Britain. Out with the old and in with the fabulous new!

Romanise, Modernise, Glamorise! Classic fashionadvice for Brittania

by Claudius Campus

Celtic fashions have been limited by the colours and fabrics available on the high street of your local village, and in fact, that’s part of the problem. The lack of urbanisation is like totally limiting the availability of exciting new ideas and sartorial innovation. But before we can innovate, we must cleanse. Let me tell you about what you should definitely be purging from your wardrobe. Those 50AD looks have got to go… .

In terms of fabric, Celtic mainstays such as wool and linen will retain their popularity, spinning wool will remain a favourite activity for you ladies at home, even if you become one of the Romanised. For the exclusive and luxurious classes, you will find that silk is just as desirable amongst the Romans as it is for you now, though of course most clothes are restricted to silk as an accessory to really set off a look, rather than as the main fabric of a garment. The revolution will be in colours.

The Celtic tradition of multicolour combination dyeing, which superstitions say must be done out of sight of all those men-folk, is heading out faster than Julius returned to Rome. Bright colours and vivid patterns stunned the Romans when they first arrived, and who can blame them, I mean, woad, urine and copper-based colouring? Are you serious? The busy swirls and checks of yesteryear do not appeal to the more subtle Mediterranean sensitivity, think less is more when going for that progressive first century AD look.

Take a long hard look at that Celt bling, and toss it out.Golden torcs simply do not feature in the Roman look, the thick bands made of gold, iron and silver might adorn the wealthy of Britain but Claudius wouldn’t be caught dead in those things, girlfriend!

Let me just address the vicious gossip about kilts. They are not part of the Celtic repertoire, despite what you may have heard (the Romanisation of British glamour will bring something closer to those garments to us, more on that later). The truth is the Celtic cuts of choice are the trouser and the sleeved tunic. Yes, they do say fashion is cyclical, but for now you won’t be needing those trousers for quite some time so get that man in your life to dispense with them.

Have you tossed them yet?I hope so,because now we can startthe fun bit: what you need to find to get that Romanised look which will be the height of desirability for the next few hundred seasons. These boys are here to stay (so embrace it!) and the Roman looks will cover soldiers, slavesand citizens alike.

The Toga, a Must-Have

The Roman trademark is the toga.It isgreat for parties, but won’t be worn by all. Not least because even when you have slaves they still struggle to tie it and doing it alone is just not going to happen. High fashion is not for the lowly, you know.

From the second century BC onwards this classic garment has been restricted to men only, girls get your own thing, it’s the boys time to shine! Not just any men mind you, only a citizen can wear one of these woollen garbs. Remember the Toga is not there for practicality, that’s what makes the toga special. If you have the time to flounce around in a toga made from up to five meters of finely woven wools from Apulia or Tarentum, then people will know you are just too fabulous to set foot in a field, and who wants muddy sandals anyway? The toga look is about letting it all hang out.

The toga is the must-have accessory for many social occasions, but remember to calibrate according to your status. The young men of Rome (I’m blushing just to think of them) look dashing in their toga virilis. Priests have longer togas which double as a hood, which just looks super, and comes in colours or with a go-faster stripe. A general on his triumph might pull out all of the stops and go for a toga picta, the coloured toga, to make him stand out in the crowd.And remember,because you are in mourning, it doesn’t mean you can’t look good. A toga pulla, in dark coloursallows you toshow respect for the dead whilst simultaneously cutting a dash.Is your husband – or lover – running for political office?Hehas to be whiter-than-white, sofind hima toga candida.You’ll see the toga candida – bright wool coated in white chalk – on those running for office. That’s why they are called ‘candidates’ in the first place. Do remember, the Toga worn over a naked torso is just not on nowadays. It’s all about the toga-over-tunic combination.

Can I let you into a secret, darling? If your Toga won’t hang properly,then have your slaves put weights or even wooden struts into it to make sure it looks just right, folds and all.

Work-Attire

For the working man the Roman collection features a number of functional, yet fashionable looks. I’ll be honest with you, most of them are tunic based. Tunic and belt, to be precise. The tunic hangs loosely across the shoulders and hasa swooping hem cut above the knee. Simple, stylish: super. Combine this with a leather shoe or sandal for a down-to-earth look.

Senators and equestrian class men in Rome prefer a tunic with two vertical stripes coming down across each side of the chest, thicker stripes for senators, thinner for the equestrian (horse owning) class. Purple stripes are hottest of all. Purple can only be attained through harvesting the secretions of certain marine molluscs,making the colour rare and expensive.This exclusivity is the secret of its enduring appeal.

The current look for the tunic ismid-lengthwith aloose fitting sleeve. Slaves and freedmen will prefer more affordable Spartacan tunics from lower quality wool, thus darker.

Ladies, Be Fashionable Without a Sweat

All my Roman ladies, for beauty tips I’ll refer you to the Egyptians, but the must have item for you is the stola, a longer version of the male tunic. The stola hangs low, almost tothe ground. You can set off your stola by wearing undergarments – like the tunica interior – beneath, ensuring that this is longer than the stola.It’s all about layers of clothing as this will show admirers your wealth. Dying hems will add that touch of class to the look. For a more textured style combine with a palla, a lighter weight and feminine version of the toga. The beauty of the palla is its versatility. Wearing it as a hood will even give you… a modest look!

Female clothing is not required to conform to societal rules in terms of colouring, so you can work a blue, yellow or red look with combinations, butremember to avoid busy patterns in the Celtic style.

Women of Rome protect themselves from the heat with parasols and fans, avian inspired designs feature feathers to add natural colours. Glass balls may be held to keep the palms cool, asa fashionable woman of leisure should never be seen to work up a sweat. However, Romanladiesin Britannia may be more concerned with avoiding the rain than moderating the heat.

Roman Coiffure

Talking of rain, showers could really ruin the most important feature of your Romanised style, the hair. Elaborate and time consuming styles are definitely in. Huge curled crests will attract not only nesting birds but also eligible young men. No style is too elaborate. Decorative hairpins of intricately carved precious metals or bone will hold these looks in place and add glamour.

Men’s hair will be much smarter than in Celtic times, the beards, moustaches and long liberated styles that have dominated male coiffures will be replaced by dashing clean shaves and neat trims, although the upcoming Senator Trajan looks set to change thatwith his neat bearded look.

Dress to Conquer in Military Chic

Military chic will be big in the new collections, think sword and sandals. Helmets are definitely in, with layered scale armour or chain mail which provides chic and effective protection from missiles and sharp weapon strikes. These are worn over coloured tunics in classic red or blue.

Rank and file soldiers will want to top their outfits by wearing the trademark helmets, with protective back neck guard and attached plates over the cheeks, providing protection without limiting visibility. Standard bearers may want to add a symbolic fur to make them stand out on the battlefield. Higher ranks will be able to personalise, attach horse-hair in horizontal or straight-on crests to draw the attention of the crowd. Let the enemy know they are bested in strength and style.

Sandals have great functionality, yet wearing with socks is a clichd fashion no-no, but I predictthis will be thrown on its head by Roman designers during cold winter seasons.Insert nails into your sandals -pointy side out! -for better grip when standing in the shield wall. Greaves worn on the shins protect from attacks around the shins, but don’t expect this to become popular until later imperial times. In downtime, go with the classic tunic and combine with a leather shoe.

These bold looks are about to revolutionise world fashion. Romanise now to fit in and ingratiate yourself to the conquerors of Britain. Cultural conformity will bring prosperity, for so long as it pleases the governor. Remember, you can’t fight the trends and you sure as hell don’t want to fight the legions so, Romanise, Modernise, Glamorise!

This week a group of archaeologists and volunteers from

This week a group of archaeologists and volunteers from  The warrior Queen, the avenging mother, the woman scorned. Ask any English person who led ‘us’ in the fight against Rome and they will tell you about a woman whose fame outweighs her achievements. Called

The warrior Queen, the avenging mother, the woman scorned. Ask any English person who led ‘us’ in the fight against Rome and they will tell you about a woman whose fame outweighs her achievements. Called

!["[She had] a great mass of the tawniest hair fell to her hips; around her neck was a large golden necklace" "[She had] a great mass of the tawniest hair fell to her hips; around her neck was a large golden necklace"](http://heritage-key.com/medialink/files/queen-boudicca.jpg) Dio mentions worse still: impalement of noblewomen followed by the cutting off of their breasts, human sacrifice and debauched celebrations after the massacre.

Dio mentions worse still: impalement of noblewomen followed by the cutting off of their breasts, human sacrifice and debauched celebrations after the massacre. Suetonius Paulinus chose a location where his two sides were flanked by a gorge, and his rear protected by dense forest. Tacitus’ father-in-law was Agricola, future governor of Britannia, who fought in the battle under Paulinus, and this connection gave Tacitus special insight into what happened next. We are told Paulinus made a speech to his troops:

Suetonius Paulinus chose a location where his two sides were flanked by a gorge, and his rear protected by dense forest. Tacitus’ father-in-law was Agricola, future governor of Britannia, who fought in the battle under Paulinus, and this connection gave Tacitus special insight into what happened next. We are told Paulinus made a speech to his troops: This did not stop the reprisals. Paulinus led punitive actions against any remaining opposition, and in doing so only exacerbated relations with the populace. By this time

This did not stop the reprisals. Paulinus led punitive actions against any remaining opposition, and in doing so only exacerbated relations with the populace. By this time

Georgiana Aitken, Head of Sale, Antiquities at

Georgiana Aitken, Head of Sale, Antiquities at  We’ve come a long way from the time when Ugg would mutter inanities to Uggetta in the cave, present her with a wad of crushed up flowers and move in for the kiss- and if she resisted he would reach for his club, gives it the old ‘knock on the head and drag away’ routine. Nowadays, for example, we do all the inanities on dating websites or in noisy bars. The rules of romance and courting have been shifting rapidly in the last 50 years and now many people are so clueless as to what they are supposed to do that they’re paying

We’ve come a long way from the time when Ugg would mutter inanities to Uggetta in the cave, present her with a wad of crushed up flowers and move in for the kiss- and if she resisted he would reach for his club, gives it the old ‘knock on the head and drag away’ routine. Nowadays, for example, we do all the inanities on dating websites or in noisy bars. The rules of romance and courting have been shifting rapidly in the last 50 years and now many people are so clueless as to what they are supposed to do that they’re paying

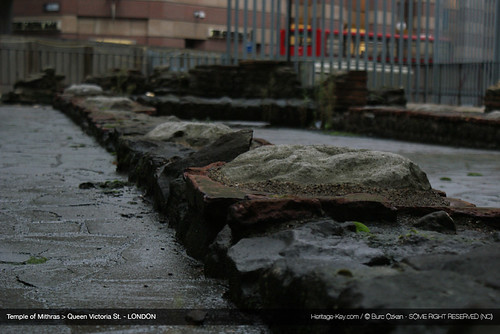

After ascending the stairs to leave the underground temple, with its impressive ground level faade, worshippers would find themselves within the Roman wall and surrounded by the hustle and bustle of

After ascending the stairs to leave the underground temple, with its impressive ground level faade, worshippers would find themselves within the Roman wall and surrounded by the hustle and bustle of