The Venus of Orkney, a 4,500-year-old Neolithic sandstone figurine hailed as Scotland’s earliest depiction of a human face, has been a darling of British archaeology since it was excavated last year on the remote island of Westray. Now, the Venus, which earned a nomination at the recent British Archaeology Awards, will have to share the limelight archaeologists at the Links of Noltland site on Westray have uncovered a second remarkable Neolithic figurine, less than 100 feet from where the Venus was discovered. Like the Venus, the recently excavated figurine is a tiny, delicate pendant-like figurine. Standing less than two inches…

-

-

Czech archaeologists have excavated remains of a prehistoric settlement in Arbil, north Iraq, which could date back as far back 200,000 years, placing it among the earliest evidence of hominid activity in the region. The expedition, led by Dr. Karel Novacek from the University of West Bohemia in Plzen, unearthed clusters of stone artifacts at the bottom of a 9-meter-deep pit dug just outside the tell in Arbil. Novacek recently explained to Heritage Key that the excavated stone tools, comprised of flakes, scrapers and cores, can be traced back to the Late Middle Paleolithic Age (200,000-40,000 years before present). The discoveries align chronologically with…

-

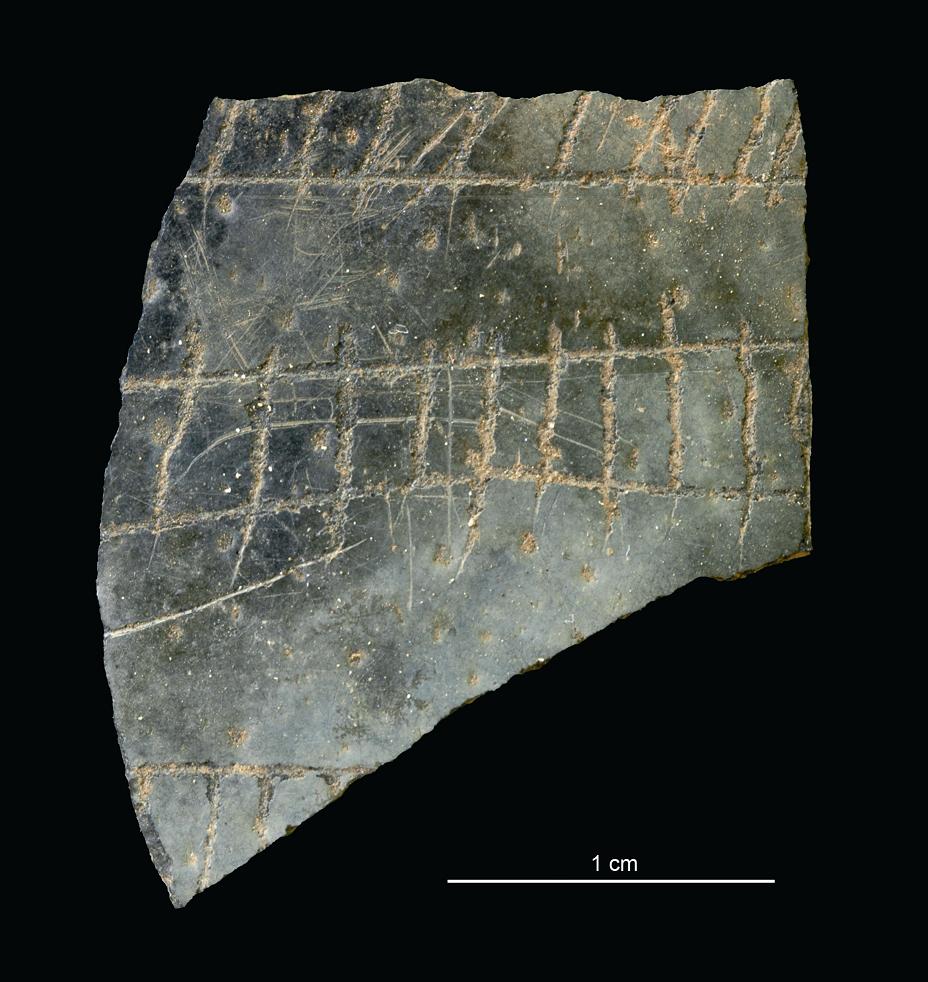

Archaeologists in South Africa have recently unearthed some of the earliest evidence of human behavior – a cache of ostrich eggs dating back 60,000 years, etched with intricate geometric designs. The abstract carvings are signs of what archaeologists call ‘symbolic thinking,’ a capacity particular to Homo sapiens. Unlike earlier hominids, our brains allow usto affix meaning to objects, to draw associations, to recognize and create symbols.Symbolic thinking is the roots ofwriting, language and art; it is,to risk grandiosity, what makes us human. So when the team at Diepkloof Rock Shelter, led by prehistorianPierre-Jean Texier, dug up the60,000-year-old decorated ostrich eggs,…

-

The remnants of a royal palace built by the family of ancient Romes legendary tyrant king, Tarquinius Superbus (Tarquin the Proud), have been unearthed at Gabii, an ancient site 12 miles south of Rome, according to reports from archaeologists on Thursday. Excavators believe that the palace, which dates back to the 6th century BC, was the home of Tarquinius Superbuss son, the notorious prince Sextus Tarquinius. Recovered fragments of the palaces terracotta roof display an image of the minotaur, a family emblem of the Tarquins, which has led archaeologists to suggest that it was home to many generations of Tarquins.…