Attribution: Photo by Maggie Bryson Garry Shaw Egyptologist and writer 7 April 1981 Dr. Shaw studied archaeology at the University of Liverpool from 1999 – 2002, and then stayed on in Liverpool to study for an MA (2002 – 2003) and PhD (2004 – 2008) in Egyptology, only taking a year off to go explore China. His main area of research has been elite life and architecture in Egypt’s New Kingdom, with the extent of the pharaoh’s personal authority in day-to-day political affairs being the subject of his first book, published in 2008. Subsequently he has written academic articles on…

-

-

A cat wanders by, leading to myself, the guard, my two friends, and the cat being the only occupants of the ruined city of Fustat on this particular day; it was originally home to roughly 200,000 people. This is an unexpected experience for Cairo solitude in the city. The Medieval Capital Fustat, the medieval capital of Egypt founded in 642 AD by General Amr Ibn el-As, was burnt to the ground (according to Arab tradition) roughly five hundred years later by order of the Vizier Shawar. Frankish crusaders were on their way, and he decided that it was better to…

-

If youve ever wanted to own a perfect hand-crafted piece of traditional Egyptian pottery made by a man with only one thumb and one eye I can tell you exactly where to go. His name is Salah and he lives in Fustat, in the area better known today as Coptic Cairo. Getting to Fustat Its an easy journey, you can take the metro from downtown Cairo there in no time at all, roughly only fifteen minutes. Then, after arriving, you get to confound the local tourist police by walking away from all the wonderful ancient churches, and straight down the…

-

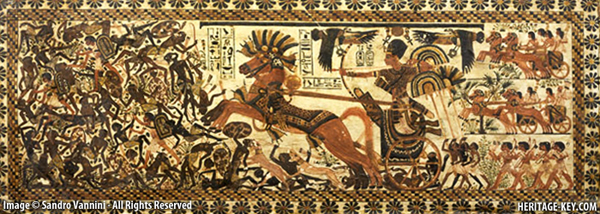

Although there is copious evidence for the Egyptian kings statues, huge depictions on temple walls, stelae the actual reality of the day-to-day work and personal authority of these individuals is often ignored in favour of discussions of divinity, art and ideology. There is good reason for this. Despite the extensive amount of evidence available to scholars, everything is shrouded in a thick layer of ideological presentation that masks the reality of the situation. This makes it difficult to separate fact from fiction: what are we to envision the king did every day? Initially, just for fun, it is interesting to…

-

Driving through the desert in search of whales sounds counterproductive, but I had been assured that if I hired a jeep and drove seventy kilometres from Egypts Faiyum Oasis out into the Sahara this is indeed what I would find. If this was a ruse it was a clever one, and UNESCO were in on it. The cream coloured 4×4 arrived at nine AM. Perfectly on time a good sign. The driver, Mohammed, was a youngish man, perhaps in his early thirties, sporting a thick goatee beard and wearing a red and white chequered headscarf. He smiled and shook my…