Recent news reports suggest that Britain’s north-south divide is still alive and as pronounced as ever. Whether you’re talking about heart disease, house prices or teenage pregnancy, statistics show that the invisible line that divides the north of Britain from the south is all too real.

Running from the Bristol channel up to somewhere just north of Lincoln (placing Wales and most of the West Midlands in the ‘north’ half of the UK), it’s an insurmountable line that separates the traditionally affluent south and the poorer north (although there are exceptions to the rule on both sides).

So how did the Brits arrive at such a divided society? Far greater brains than mine have pondered this question – and have come up with some insights. Recent history could point to the closure of industry and in particular coal mines in the north of England and in South Wales, but the line existed way before the ’70s and ’80s. Alan Baker and Mark Billinge published Geographies of England: the North-South Divide after noticing the similarities in wealth distribution of early 14th century Britain and late 20th century society. They looked into the rise of London in the Middle Ages, the urbanisation of agricultural Britain and the Industrial Revolution as roots of the disparity in wealth between the north-west and the south-east. Interesting stuff, but were there signs of a north-south divide even further back in time?

Severus Divides Britain in Two – Forever?

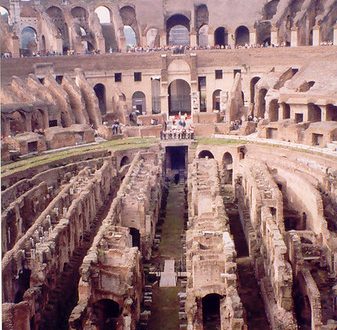

We know for sure that Britannia was first slashed in two by the Romans in 197 AD (or sometime after that). The emperor Septimius Severus appointed Londinium (London) as capital of the new province Britannia Superior, while Eboracum (York) was the capital of Britannia Inferior. The dividing line between the two provinces of Britannia hasn’t been clearly established, but it’s believed to have included Wales and East Anglia, with Britannia Inferior ending at Hadrian’s Wall, just south of the Scottish border.

Severus’s division of Britain into two provinces was a consequence of a power struggle between him and Clodius Albinus, governor of Britain. Severus had seized control of the empire in 193 AD after executing the emperor Didius Julianus in Rome, while Albinus had the support of three legions in Britannia (based at the Roman forts at York, Caerleon and Chester). Severus offered Albinus the title of Caesar, which he accepted, at least for the time being.

Three years later, in 196, Albinus and his armies invaded Gaul, officially challenging Severus’s rule of the empire. Crucially, it was Albinus’s power-base in Britannia that enabled him to mount this attack. He was an experienced and respected military commander, but Severus defeated him at the Battle of Lugdunum (near modern-day Lyon), before turning his attention to the source of the disturbance Britannia.

The Military North vs the Civilian South

The emperor realised that the governor of Britannia had too much power and could pose a potential threat to the stability of the empire. In a classic ‘divide-and-rule’ move, Severus installed two governors instead of one, each with his own half of the province.

Following this, tribes in northern Britannia continued to rebel against the Roman rulers and some reports by Cassius Dio say that much of the northern half of Britannia was overwhelmed with rebellions from local tribes. Severus spent time at Eboracum, the capital of the new northern province, on a campaign to put down the insurgent tribes. Meanwhile Londinium remained the centre for commerce and government of Britannia Superior.

Could it have been this split in 197 AD that had such a far-reaching effect on wealth distribution in Britain today? While Britannia Inferior was associated with military forts, the south-east of the province was considered the ‘civil’ zone and a far greater number of Roman villas have been found in the area of Britannia Superior. While the north fought to control local tribes, the south-east had an easier time and prospered. It could be that this set the blueprint for our North-South divide.