Scholars often refer to cultures who used monumental architecture for political purposes as a ‘theater-state’ and boy could the Aztecs put on a good show! When the Spanish conquistadors first glimpsed Tenochtitlan at its zenith in 1519, the Mexica capital and its suburbs surrounding Lake Texcoco was home to over a million inhabitants whose lives were punctuated by numerous festivities centered around amphitheaters and religious shrines scattered across the city. It is no wonder then, that the Spanish, many of whom were natives of Extremadura, a province of western Spain that was once a part of Roman Lusitania and birthplace…

-

-

The cast and crew of Percy Jackson and the Olympians: The Lightning Thief didn’t have to go all the way to Athens to film the hydra scene in the Parthenon. They just booked some time in a reconstruction of the Parthenon in Nashville, Tennesse. Perhaps in the future, as the role of CGI increases in movies, they will be able to use a virtual version. I visited the Nashville Parthenon, as well as Second Life’s virtual reconstruction, to find out what the Parthenon of Athens was really like in the time of the ancient Greeks. The Nashville Parthenon I know,…

-

“To get attention these days to penetrate the market, you’ve got to be pretty outrageous and prepared to go there!” exclaims Lucy Lawless, one of the stars of the new STARZ miniseries Spartacus: Blood and Sand. After watching ten episodes of the new series, I would have to agree that the word “outrageous” was one that certainly popped into my head! I had read that the network executives at STARZ had told series producers that they wanted a production with more sex and violence than any network had ever produced and from the looks of things, they pretty much got…

-

Virtual atalhyk is one of the most well-researched and painstakingly executed ancient world reconstructions in Second Life. But with the rent due, and funding tight, can the researchers keep the environment alive? I spoke to creator Colleen Morgan about the problems of creating reconstructions for high-rent platforms. Model Town Over 9,000 years ago, a group of Neolithic people began to build a mud-brick settlement on a hill overlooking the Konya Plain of Turkey. The structures were placed closely together and the people moved from place to place by accessing the roofs with interior or exterior ladders. Scholars believe communal activities…

-

Virtual Çatalhöyük is one of the most well-researched and painstakingly executed ancient world reconstructions in Second Life. But with the rent due, and funding tight, can the researchers keep the environment alive? I spoke to creator Colleen Morgan about the problems of creating reconstructions for high-rent platforms. Model Town Over 9,000 years ago, a group of Neolithic people began to build a mud-brick settlement on a hill overlooking the Konya Plain of Turkey. The structures were placed closely together and the people moved from place to place by accessing the roofs with interior or exterior ladders. Scholars believe communal activities…

-

Once more, the J. Paul Getty collection of antiquities may be depleted due to the repatriation of a 4th century BC bronze called ‘Statue of a Victorious Youth‘ thought to be the work of Lysippos, a Greek sculptor who flourished under the patronage of Alexander the Great. The work was originally salvaged from the depths of the Adriatic sea near the Italian town of Fano in 1964 by Italian fishermen trawling in international waters. The real irony in the Italian court’s ruling ordering the confiscation of the work from the Getty is that the bronze was probably on its way…

-

Westworld, starring Yul Brynner, has been one of my all-time favorite movies since it was released back in 1973. Envisioned by Michael Crichton, Westworld was a fictional theme park where tourists could go to experience life in another historical period. The park had a medieval world, a Roman world and, of course, Westworld, a recreation of the old American west. Each world was populated with carefully programmed androids who behaved as people from each time period would have during their normal daily activities. Guests of the park were given appropriate clothing and instructed to assume the role of a character…

-

In an effort to share their extensive collection of pottery from the American southwest with both museum and internet visitors, the Arizona State Museum is collaborating with the Center for Desert Archaeology on the Virtual Vault Project. Models of each vessel are being created using 3DSOM Pro, a tool for automatically generating 3D models from photos of an object. The software is produced by Creative Dimension Software Ltd. “The Vault will go far beyond static electronic exhibit modules that depict a vessel and list its type and ware designation, description, dating, and function – instead, it is being developed as…

-

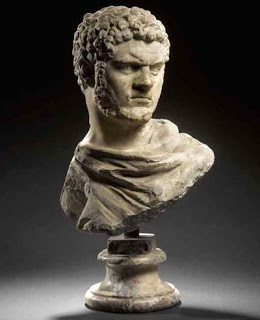

A bust of the Roman Emperor Caracalla will be auctioned off October 28 by Bonham’s. The auction house estimates the bust will bring 250,000. The lot description says the bust dates to the period after he murdered his brother and co-emperor Geta and their website lists the provenance as the current owner having a receipt from Mr. Dennis Leen, Beverly Hills, California dated 1976. But Dennis and Leen is not a individual but an exclusive interior design company in Beverly Hills who curently specialize in high quality antique reproductions. This information brought me up short. Is a receipt from a…