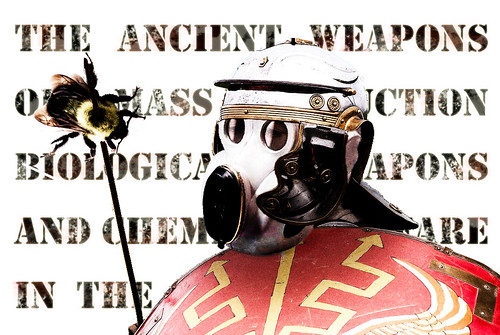

In 1972, the U.S. signed the Biological and Toxic Weapons Convention, which banned the “development, production and stockpiling of microbes or their poisonous products except in amounts necessary for protective and peaceful research.” By 1996, 137 countries had signed the treaty. But was this this the first attempt at establishing rules for ‘humane warfare’? No, antiquity beat us to it, although they – also – often did not adhere to their own rules. The Brahmanic Laws of Manu, a Hindu treatise on statecraft dating back to the 5th Century BC, forbids the use of arrows tipped with fire or poison, but advises poisoning food and water. Kautilya’s Arthashastra, one of the world’s earliest treatises on war, advocates surprise night raids and offers recipes for toxic smokes and plague-generating toxins, but it also urges princes to exercise restraint and win the hearts and minds of their foes. The Roman historian Florus denounced sabotaging an enemy’s water supply, saying the act “violated the laws of heaven and the practice of our forefathers.”

In 1972, the U.S. signed the Biological and Toxic Weapons Convention, which banned the “development, production and stockpiling of microbes or their poisonous products except in amounts necessary for protective and peaceful research.” By 1996, 137 countries had signed the treaty. But was this this the first attempt at establishing rules for ‘humane warfare’? No, antiquity beat us to it, although they – also – often did not adhere to their own rules. The Brahmanic Laws of Manu, a Hindu treatise on statecraft dating back to the 5th Century BC, forbids the use of arrows tipped with fire or poison, but advises poisoning food and water. Kautilya’s Arthashastra, one of the world’s earliest treatises on war, advocates surprise night raids and offers recipes for toxic smokes and plague-generating toxins, but it also urges princes to exercise restraint and win the hearts and minds of their foes. The Roman historian Florus denounced sabotaging an enemy’s water supply, saying the act “violated the laws of heaven and the practice of our forefathers.”

Even in antiquity, many feared the lurking consequences of unleashing what we now call chemical weapons – indeed, the ancient Greek tale of Pandora’s box offers a continuing metaphor for their use. This lack of ‘war ethics’ lead to quite a few interesting occurrences of biological as well as chemical warfare, and shows us that nearly every advanced biochemical weapon today has an ancient prototype.

Biological Warfare in Antiquity

The Hittite Plague (1320 BC) – The earliest documented case of biological warfare in the Near East was during the Anatolian War when the Hittites, even though militarily weaker than their enemies the Arzawans, won victory with a secret bioweapon. They drove rams and donkeys infected with deadly tularemia into Arzawan lands. The lethal plague was transmitted to humans via ticks and flies. Today, artificially manufactured plague germs are possible, a concept first described by ancient Romans as pestilentia manu facta, man-made pestilence.

Armis Bella Non Venenis Geri. (War is fought with weapons, not with poisons.) – A Roman Lawyer

Mad Cow (10th Century BD) – A witch named Chrysame was the worlds first military commander who was also adept in pharmacology. who used drugs to cause temporary insanity in the enemy, during the Greek colonization of Ionia in about 1000 BC. Polyaenus in his Stratagems tells us: “Possessing great skill in the occult qualities of herbs, she chose out of the herd a large and beautiful bull, gilded his horns, and decorated him with garlands, and purple ribbons embroidered with gold. She mixed in his fodder a medicinal herb that would excite madness, and ordered him to be kept in the stall and fed upon it. The efficacy of this medicine was such, that not only the beast, who ate it, was seized with madness; but also all, who ate the flesh of it, when it was in such a state, were seized with the same insanity. When the enemy encamped against her, she directed an altar to be raised in sight of them; and after every preparation for a sacrifice had been made, the bull was brought forth. Under the influence of the medicine, the bull broke loose; he ran wild into the plain, roaring, and tilting at everything he met. The Erythraeans saw the victim, intended for the enemy’s sacrifice, running towards their camp, and considered it as a happy omen. They seized the beast, and offered him up in sacrifice to their gods; everyone, in participation of the sacrifice, ate a piece of the flesh. The whole army was soon afterwards seized with madness, and exhibited the same marks of wildness and frenzy the bull had done.”

No Chance at Recovery (4th Century BC) – Scythian archers tipped their arrow tips with snake venom, human blood, and animal feces to cause wounds to become infected. There are numerous other instances of the use of plant toxins, venoms, and other poisonous substances to create biological weapons in antiquity. (And of course, man used toxic arrows already way earlier to hunt for large game.)

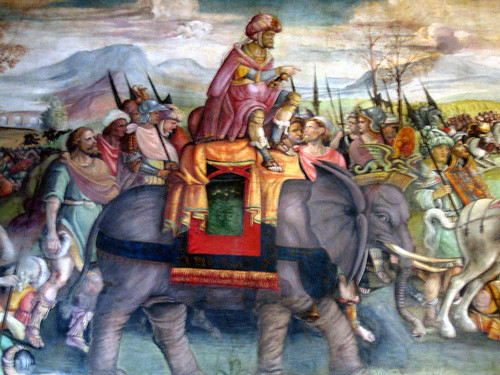

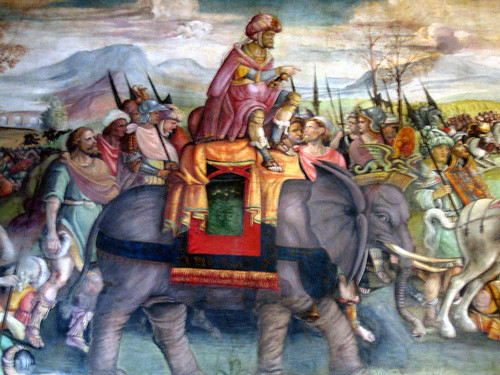

Bombs, Snakes and Scorpions Away (184 BC) – Hannibal of Carthage had clay pots filled with venomous snakes and instructed his soldiers to throw the pots onto the decks of Pergamene ships. And in about AD 198, the city of Hatra repulsed the Roman army led by Septimius Severus by hurling clay pots filled with live scorpions at them.

Bombs, Snakes and Scorpions Away (184 BC) – Hannibal of Carthage had clay pots filled with venomous snakes and instructed his soldiers to throw the pots onto the decks of Pergamene ships. And in about AD 198, the city of Hatra repulsed the Roman army led by Septimius Severus by hurling clay pots filled with live scorpions at them.

Send in the Bees! (1st Century BC) – At Themiscyra, a stubborn Greek outpost, Romans tunneling beneath the city contended with not only a charge of wild beasts but also a barrage of hives swarming with bees. A rather direct approach to biological warfare?

Send in the Bees II (67 BC) – Pompey was leading a campaign against Mithridates, the king of Pontus. As his troops passed along the roads in the Trebizond region (Turkey), the people of the region, the Heptakometes, put out honey as tribute. The honey was a local product, and it contained acetylandromedol, a grayanotoxin (as the bees visited the local rhododendron species). This toxin produced nausea and hallucinations, and perhaps some deaths, among the troops who consumed it, and three maniples of the Roman army were attacked and destroyed while intoxicated. The Roman commanders should have studied their classics more closely – Xenophon, in his Anabasis, tells of what happened when his troops consumed some of the local honeycomb in the same area in 401 BC – although he was luckier than Pompey, as the Persians who were pursuing him did not attack during the four days his army took to recover.

And last but not least, and not entirely ancient but definitely worth mentioning due to the catastrophic consequences for both friend and foe. Was the bubonic plague the first ‘weapon of mass destruction’?

Tartar army accountable for the Black Death? (1346 AD) – The Mongol army in 1346 launched a biological assault that may have gotten out of control – big time. While besieging the city of Kaffa (modern-day Crimea), soldiers hurled their own corpses of bubonic plague victims over city walls. Fleas from the corpses infested people and rats in the city. Plague spread as people and rats escaped and fled. Some experts believe the refugees from Kaffa travelling to Constantinople, Genoa, and Venice triggered the great epidemic of bubonic plague – the “Black Death” – that swept Europe three years later, killing 25 million people.

Chemical Warfare in the Ancient Times

Soul-Hunting Fog (10th Century BC) – The Chinese were the original masters of chemical warfar: Chinese writings contain literally hundreds of recipes for the production of poisonous or irritating smokes for use in war, and many accounts of their use. Thus we know of the arsenic-containing “soul-hunting fog” and the irritating “five-league fog” (formed from a slow-burning gunpowder to which a variety of ingredients, including the excrement of wolves, was added to produce an irritating smoke).

Is Your Army Potty-trained? (6th Century BC) – Lead by Solon of Athens, the ancient Greeks, besieging a city called Krissa, poisoned the water in an aqueduct leading from the Pleistrus River with the herb hellebore: it causes violent diarrhea.

Is Your Army Potty-trained? (6th Century BC) – Lead by Solon of Athens, the ancient Greeks, besieging a city called Krissa, poisoned the water in an aqueduct leading from the Pleistrus River with the herb hellebore: it causes violent diarrhea.

The Earliest Recorded Use of Gas Warfare in the West (5th Century BC) – During the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta, Spartan forces besieging an Athenian city placed a lighted mixture of wood, pitch, and sulfur under the walls hoping that the noxious smoke would incapacitate the Athenians, so that they would not be able to resist the assault that followed.

Burning Bombardment (332 BC) – The citizens of the doomed port of Tyre catapulted basins of burning sand at Alexander the Great‘s advancing army. Falling from the sky, the sand would have had the same ghastly effect as white phosphorus.

Smoke Them Romans Out (187 BC) – The inhabitants of the town of Ambracia in Epirus dealt a setback to Roman soldiers seeking to tunnel under their walls: “Filling a huge jar with feathers, they put fire in it and attached a bronze cover perforated with numerous holes. After carrying the jar into the mine and turning its mouth toward the enemy, they inserted a bellows in the bottom, and by pumping the bellows vigorously they caused a tremendous amount of disagreeable smoke, such as feathers would naturally create, to pour forth, so that none of the Romans could endure it. As a result the Romans, despairing of success, made a truce and raised the siege.” (Cassius Dio, Roman History, Book XIX)

Close Your Eyes and Pray (80 BC)– According to the historian Plutarch, the Roman general Sertorius had his troops pile mounds of gypsum powder by the hillside hideaways of Spanish rebels. When kicked up by a strong northerly wind, the dust became a severe irritant, smoking the insurgents out of their caves.

Early Riot Control (178 AD) – A Chinese ruler put down a peasant revolt by encircling the rebels with chariots heaped with limestone powder. The charioteers pumped the powder into a primitive tear gas even more corrosive and lethal than its modern equivalent. The peasants didn’t stand a chance.

Sulfur and Bitumen gas fatal for Roman Sapeurs (256 AD) – During the final siege of the city Dura-Europos (Syria), the attackers burrowed beneath the walls in order to breach the Roman defenses; the Romans heard this and started digging a countermine to fend off the assault. But the Persians prepared a nasty surprise, pumping lethal fumes from a brazier burning sulfur crystals and bitumen, a tarlike substance, with bellows into the Roman tunnels. It was concluded that 20 Roman soldiers unearthed beneath the town’s ramparts did not die of war wounds, as previous archaeologists had assumed, but from poison gas.

Antidotes and Solutions

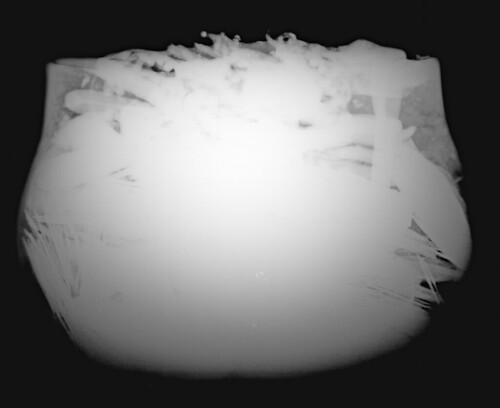

Mithridatium (2th Century BC) – Italian archaeologists excavating a Roman villa near Pompeii discovered a large vat containing the residue of whatever had been stored in the container since AD 79. Tests of the residue revealed a mixture of powerful medicinal plants, including opium poppy seeds, along with the flesh and bones of reptiles. According to the archaeologists, the vat may have been used to prepare a secret universal antidote believed to counteract all known poisons. This concoction, a combination of small doses of poisons and their antidotes, called Mithridatium, had been invented by King Mithridates VI of Pontus, a brilliant military strategist and master of toxicology, about one hundred years earlier. His recipe was perfected by the Emperor Neros personal physician and became the worlds most sought-after antidote, long prescribed for European royalty.

Mithridatium (2th Century BC) – Italian archaeologists excavating a Roman villa near Pompeii discovered a large vat containing the residue of whatever had been stored in the container since AD 79. Tests of the residue revealed a mixture of powerful medicinal plants, including opium poppy seeds, along with the flesh and bones of reptiles. According to the archaeologists, the vat may have been used to prepare a secret universal antidote believed to counteract all known poisons. This concoction, a combination of small doses of poisons and their antidotes, called Mithridatium, had been invented by King Mithridates VI of Pontus, a brilliant military strategist and master of toxicology, about one hundred years earlier. His recipe was perfected by the Emperor Neros personal physician and became the worlds most sought-after antidote, long prescribed for European royalty.

Pigs vs. Elephants – War pigs are pigs said to have been used – at most, rarely – in ancient warfare as a countermeasure to war elephants. Pliny the Elder reported that “elephants are scared by the smallest squeal of the hog”. The Romans would later use the squeals of pigs to frighten Pyrrhus’ elephants. Procopius, in book VIII of his History of the Wars, records the defenders of Edessa using a pig suspended from the walls to frighten away Khosrau’s siege elephants. (War Pigs – as encountered in Rome: Total War – are most likely a myth.)

Stopping the Plague (4th Century BC) – Hippocrates is said to have saved Athens from a big plague: “During the gold century of Perricles, a big plague invaded Athens when a lot of the citizens died. The greatest doctors of Greece came to Athens but they could not save the town. Then Pericles called on Hippocrates for help. He made people built and set light to big fires around the town in order to destroy the bacteria. In this way Athens was saved. He found this solution while he was walking in town; he saw that most of the people were infected by the plague, except for the blacksmiths who were next to the fire all day.”

Combining religion and science is impossible unless you’re willing to get err… creative? Not quite true: although they might quarrel about the details, archaeologists and the scriptures do quite agree on major historical facts such as the destruction of Jericho, the rule of Herod the Great as well as King David’s. Archaeology can help determine the lifestyle and practices of people living in biblical times and such shed light upon the Hebrew Scriptures and the New Testament. The biblical archaeology school focusses on doing exactly this, and Professor Don Benjamin in his book ‘

Combining religion and science is impossible unless you’re willing to get err… creative? Not quite true: although they might quarrel about the details, archaeologists and the scriptures do quite agree on major historical facts such as the destruction of Jericho, the rule of Herod the Great as well as King David’s. Archaeology can help determine the lifestyle and practices of people living in biblical times and such shed light upon the Hebrew Scriptures and the New Testament. The biblical archaeology school focusses on doing exactly this, and Professor Don Benjamin in his book ‘

This is just the beginning of ‘deciphering’ the Harappan symbols. The international team hopes to compose a grammar of Indus signs, as they’ve already found that certain placements of characters in the text to be more likely: a “fish” sign most frequently appeared in the middle of a sequence, a U-shaped “jar” sign toward the end.

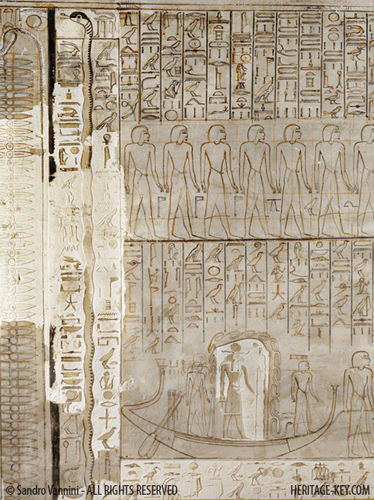

This is just the beginning of ‘deciphering’ the Harappan symbols. The international team hopes to compose a grammar of Indus signs, as they’ve already found that certain placements of characters in the text to be more likely: a “fish” sign most frequently appeared in the middle of a sequence, a U-shaped “jar” sign toward the end. Recently the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities has shared it’s worries about the future of the tombs in the Valley of the Kings with the world. Now they share more details on the planned solutions: ventilation systems, special lighting and… well, we expected a replica of KV62, but we’re getting an entire new Valley of the Kings on the cliff side of the real one.

Recently the Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities has shared it’s worries about the future of the tombs in the Valley of the Kings with the world. Now they share more details on the planned solutions: ventilation systems, special lighting and… well, we expected a replica of KV62, but we’re getting an entire new Valley of the Kings on the cliff side of the real one.

The Antikythera Mechanism Research Project detected in July 2008 the word “Olympia” on a bronze dial thought to display the 76 year Callippic cycle, as well as the names of other games in ancient Greece.

The Antikythera Mechanism Research Project detected in July 2008 the word “Olympia” on a bronze dial thought to display the 76 year Callippic cycle, as well as the names of other games in ancient Greece.