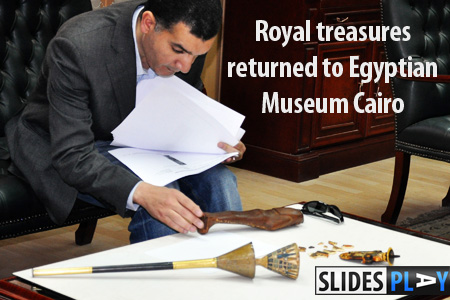

Four ancient Egyptian artefacts belonging to Tutankhamun, and missing from the Cairo Museum since the January Revolution have been returned, announced Dr. Zahi Hawass, Minister of State for Antiquities, in a statement to the press. The objects returned include the gilded wooden statue of Tutankhamun standing on a skiff throwing a harpoon (JE 60710.1), part of King Tut’s burial treasure. As can be seen in the photos below, the statue suffered damage; a small part of the crown is missing as well as pieces of the pharaoh’s legs. The boat itself never left the Cairo Museum, and the artefact will…

-

-

A month and a half after the Cairo Museum break-in, Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities has posted online a listing of sixty-three objects that were found to be missing following the looting. Amongst the missing Ancient Egyptian treasures are ritual statues and a fan belonging to King Tut, Yuya’s shabtis, amulets, as well as amulets and jewellery. Final List of Objects Missing from the Egyptian Museum, as released by the SCA, March 15th 2011: Gilded Wooden Figure of Tutankhamun on a Skiff, Throwing a Harpoon (the figure) – Carter no 275c? Gilded Wood Statue of Tutankhamun Wearing the Red Crown…

-

On March 8th, International Woman’s Day is celebrating its centenary, and the Petrie Museum is joining in by honouring Victorian writer Amelia Edwards, for without her, there may have never have been a ‘Petrie Museum’. Amelia Edwards was a novelist and travel writer, as well as an Egyptologist. After visiting for the first time in Egypt 1873, she wrote a vivid account of her adventure in A Thousand Miles up the Nile. She was the driving force behind the establishment of the Egypt Exploration Fund (now the EES) in 1882 to promote the scientific exploration of Egypt and its monuments.…

-

About 5,300 years ago, a man travelling the Alps was hit by an arrow. Roughly 5,280 years later, two German tourists exploring the Italian-Austrian border discover the world’s oldest and best preserved mummy. Since, Ötzi has been examined by innumerable scientists and has received almost three million visitors. To celebrate the natural mummy’s twentieth year as a global sensation, the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology in Bolzano is dedicating a special exhibition to the Iceman. The show’s highlight – besides a peek at Ötzi’s refrigerated corpse – is a new, naturalistic reconstruction of how Ötzi would have looked, based on…

-

The source of Stonehenge’s bluestones a distinctive set of stones that form the inner circle and inner horseshoe of Stonehenge has long been a subject of fascination and considerable controversy. In the early 1920s, one type of bluestone, the so-called spotted dolerite, was convincingly traced to the Mynydd Preseli area, in north Pembrokeshire. However, the sources of the other bluestones – chiefly rhyolites (a type of rock) and the rare sandstones remained, unknown. Now geologists at Amgueddfa Cymru, the National Museum Wales, have further identified the sources of one of the rhyolite types. The find also provides the opportunity for…

-

Egypt’s Minister of Antiquities Affairs, Dr Zahi Hawass, announced today that the missing limestone statue of King Akhenaten, the likely father of Tutankhamun, has been returned to the Egyptian Museum, Cairo. To date, four objects from the preliminary list of missing artefacts have been found; the Heart Scarab of Yuya, a shabti of Yuya, the statue of the goddess Menkaret carrying Tutankhamun, and now the statue of Akhenaten as an offering bearer. Statue of Akhenaten returned The statue of pharaoh Akhenaten is one of the unique statues from the Amarna Period on display at the Egyptian Museum. It is seven…

-

An inventory check at the Cairo Museum, Egypt – two weeks after the protests at the capital lead to a break-in at the national museum – shows that not all of ancient Egyptian treasures are accounted for. Amongst the missing antiquities – ranging from little shabtis to larger stone statues – are objects that were discovered in King Tuts tomb. Dr. Zahi Hawass, Egypts Minister of State for Antiquities Affairs, announced today that the staff of the database department at the Egyptian Museum, Cairo have given him their report on the inventory of objects at the museum following the January…

-

During a short inspection tour of the Egyptian Museum, Cairo, Dr. Zahi Hawass, Egypt’s newly appointed Minister of Antiquities, has announced that the restoration of seventy objects, damaged during the failed looting attempt on January 28, has begun and will be completed within five days. The restoration project includes the statue of Tutankhamun standing on the back of a panther and a New Kingdom wooden sarcophagus, both damaged by the criminals. “One showcase in the Ahkenatengalleries was smashed; it contained a standing statue of the king carrying an offering tray. While the showcase is badly damaged, the statue sustained very…

-

The Supreme Council of Antiquities announced today that Secretary General Dr. Zahi Hawass has sent an official request for the famous bust of Queen Nefertiti to be returned to Egypt. This request was approved by the Prime Minister of Egypt, Dr. Ahmed Nazif, and Minister of Culture, Farouk Hosny, after four years of research by a legal committee composed of legal personnel and Egyptologists. Update: Response from the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation, which states the letter was _not_ signed by Egypt’s Prime Minister, and thus is not official, in the comments. The request letter was send to Dr. Hermann Parzinger,…

-

Egyptian Minister of Culture, Farouk Hosny announced today that six missing pieces from the colossal double statue of the 18th Dynasty King Amenhotep III and his wife Queen Tiye, have been discovered at the kings mortuary temple on Luxors west bank. The fragments were found during excavation work by an Egyptian team under the direction of Dr. Zahi Hawass, Secretary General of the Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA). The pieces from Amenhotep III‘s statue that were recovered come from the right side of his chest, nemes headdress, and leg. Statue fragments of Queen Tiye that were uncovered include a section…