While most people are still able to (albeit it probably a bit incorrectly) answer what an archaeologist does, anthropologists are a species less known to the general public and media. Derived from the Greek ‘anthropos’ (human), anthropology means, ‘the social science that studies the origins and social relationships of human beings’ according to the Princeton WordNet, and is most often used to refer to ‘cultural anthropology’. But anthropology student Dai Cooper is doing her bit to make the discipline just that bit more famous… on YouTube. In just a few weeks, the ‘Anthropology Song: A little bit Anthropologist’ has become…

-

-

Parts of an ancient underground drain that takes Bath’s famous hot spring water from the Roman Baths to the River Avon are to be explored for the first time in a project to survey parts of the Great Roman Drain, a scheduled ancient monument and fundamental part of the Roman Baths complex. Parts of the drain have not been explored for hundreds of years. Built by the Romans to prevent central Bath from flooding, the Great Drain still performs its original purpose, discharging water from the natural hot springs to – Bluestonehenge’s – River Avon. It definitely needs to be…

-

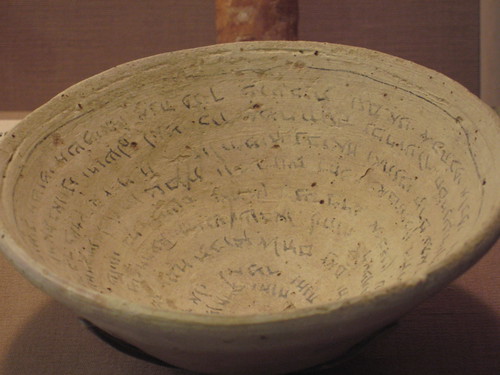

An archaeological mystery may have come to an end, after an enquiry into the origin of 654 Aramaic incantation bowls from the Schyen Collection was finally made public. The report – recently placed in the House of Lords Library – states that bowls currently finding themselves in Britain were likely to have illegally been looted after the Gulf War and should be returned to Iraq. Commissioned by the University College in London in 2005, the results of the enquiry are that the bowls were stolen from the historical site of Babylon some time after the 1991 Gulf war, and that…

-

Ruinsfrom a Han Dynasty (206 BC to 220 AD) cityhave been discovered in Wuyuan County, Hetao Plain, Chinas Inner Mongolia. Its said that the scale of the city ruins is rarely seen in Hetao Plain. In a mean while, the gold mining company is been investigated over irreparable damage done to 100 metersof theGreat Wall in their quest for the precious metal. A new Han City discovered in Wuyuan County Thenewly discovered city ruins are located in Taal Town of Wuyuan County, Bayannaoer City in Chinas Inner Mongolia and were once covered with grassland. The city wall was about 2…

-

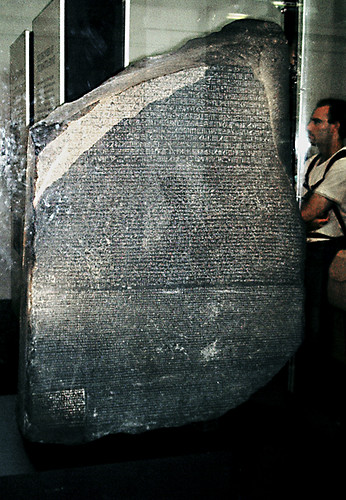

Egypt threathening to severe ties with the Louvre museum led to five looted Pharaonic steles returning to Egypt and maybe even toTetiki’stomb of which they were illegally removed. But the directory general of the SCA, Dr. Zahi Hawass, is on a quest that he hopes will lead to thehigh-profile “icons of the Egyptian identity” returning to the Cairo Museum. What’s on the wishlist? First and foremore the Rosetta Stone from the British Museum and the Nefertiti Bust from the Neues. But also a statue of Hemiunu, the bust of Anchhaf, the mask of Ka-Nefer-Neferand the painted Zodiac blasted outof theceiling…

-

When visiting King Tutankhamun’s tomb – or its virtual counterpart King Tut Virtual – did you ever notice the strange brown spotson the wall paintings? They definitely were not there when Howard Carter discovered KV62 in 1922, and nobody knows what is causing them, not even Dr. Zahi Hawass: “I always see the tomb of King Tut and wonder about those spots, which no scientist has been able to explain.” Now the Getty Conservation Institute – specialised in conservation techniques for art and inparticular forancient sites – in cooperation with the SCA will start a five-year conservation project to determine…

-

‘Reclaiming King Arthur’ -avideo produced by the University of Wales, Newport, aims to bring to life the legend of King Arthur, by examining historic evidence and the literary tradition which points to Gwent as the home of this famous character as well as to introduce an international audience to the history of this South Wales site.In thevideo – available for all to see on the University’s Instititue of Digital Learning website -Dr Ray Howell examines the relevance of King Arthur as most widely known through legend, myth, historical evidence, literature and the literary tradition which include explanation of how Caerleon…

-

It is not only at excavation sites that amazing artefacts can be discovered, but the archives of previous digs as well as the artefacts already in museums can still surprise us. Or what about the basement of the Cairo museum? Thousands of pieces, hidden away from both scholars and public. At least for now. Plans are under way to do a thorough ‘clean up’of the gigantic basement and who knows what will come to light when all items are eventually moved to the Grand Egyptian Museum? In the mean while, Dr. Zahi Hawass tells us about how a recent ‘re-discovery’…

-

The West Semitic Research Project in cooperation with the Oriental Institute are producing very high-quality electronic images of nearly 700 Aramaic administrative documents discovered in Iran. These clay tablets – in which the Aramaic texts were incised in the surface with styluses or inked on the tablets with brushes or pen – form one of the largest groups of ancient Aramaic records ever found. They are part of the Persepolis Fortification Archive, an immense group of administrative documents written and compiled about 500 B.C. at Persepolis, one of the capitals of the Achaemenid Persian Empire. Archaeologists from the Oriental Institute…

-

In a bid to bring more tourists to the town of Tiwanaku – some 64km north of Bolivia’s capital La Paz – the Bolivian Andes town put at risk it’s UNWorld Heritage Site status, and even put their Akapana Pyramid in the danger of collapse. They restored their pyramid with adobe – a clay mixture – instead of stone in what some experts are calling a renovation fiasco. Jose Luis Paz, appointed to assess the damage at the heritage site, told CourierMail the that the state National Archaeology Union erred in choosing to rebuild the pyramid using adobe, when it…