A splendid exhibition in New York – ‘The Lost World of Old Europe: The Danube Valley’ – brings to the United States for the first time more than 250 objects recovered by archaeologists from the graves, towns, and villages of Old Europe, a period of related prehistoric cultures that achieved a peak of sophistication and creativity between 5000 and 4000BC in what is now southeastern Europe. The cultures mysteriously collapsed by 3500 BC, possibly brining a shift from female to male power. The exhibition – made possible through loan agreements with over 20 museums in Romania, Bulgaria, and Moldova – features the exuberant art, enigmatic goddess cults, and elaborate metal ornaments and weapons of Old Europe.

A splendid exhibition in New York – ‘The Lost World of Old Europe: The Danube Valley’ – brings to the United States for the first time more than 250 objects recovered by archaeologists from the graves, towns, and villages of Old Europe, a period of related prehistoric cultures that achieved a peak of sophistication and creativity between 5000 and 4000BC in what is now southeastern Europe. The cultures mysteriously collapsed by 3500 BC, possibly brining a shift from female to male power. The exhibition – made possible through loan agreements with over 20 museums in Romania, Bulgaria, and Moldova – features the exuberant art, enigmatic goddess cults, and elaborate metal ornaments and weapons of Old Europe.

Long before Egypt or Mesopotamia rose to an equivalent level of achievement, Old Europe was among the most sophisticated places that humans inhabited. Some of its towns grew to citylike sizes. Potters developed striking designs; and the ubiquitous goddess figurines found in houses and shrines have triggered intense debates about womens roles in Old European society. Coppersmiths were, in their day, the most advanced metal artisans in the world. Their passionate interest in acquiring copper, gold, Aegean shells, and other rare valuables created networks of negotiation that reached surprisingly far, permitting some of their chiefs to be buried with pounds of gold and copper in funerals without parallel in the Near East or Egypt at the time.

The Lost World of Old Europe brings to an American audience, for the first time, a civilization barely mentioned in university classes but of exceptional importance within the development of human societies.

For many visitors to The Lost World of Old Europe: The Danube Valley the region and its historical context, as well as its material culture, may be largely unfamiliar. Discussions of Western civilization often move from the Venus of Willendorf to the Lascaux cave paintings and then on to Egypt and Mesopotamia, without ever mentioning the art and culture of what is known as Old Europe, an area corresponding geographically to modern-day southeastern Europe and defined by a series of distinct cultural groups that attained an astonishing level of sophistication in the 5th and 4th millennia BC.

The Lost World of Old Europe brings to an American audience, for the first time, a civilization barely mentioned in university classes but of exceptional importance within the development of human societies, said Roger S. Bagnall, Director of ISAW. Through these artifacts and their archaeological contexts, we discover that already in the 5th and 4th millennia BC the Danube basin was the hub of a trade network stretching from the Aegean to northwest Europe, as well as the home of sophisticated metallurgy, based in towns that even 4,000 later would have been considered sizable. As an institute devoted to studying the connections of ancient societies across time and space, ISAW is excited to bring these dramatic finds to New York.

The Lost World of Old Europe attempts to redefine commonly held notions of the development of Western civilization by presenting the surprising and littleknown artistic and technological achievements made by these still enigmatic peoples – from their extraordinary figurines, to their vast variety of copper and gold objects, to their stunning pottery types.

ACouncil of Goddesses?

Perhaps the most widely known objects from Old Europe are the mother goddess figurines. Fashioned by virtually every Old European cultural group, these striking miniaturized representations of females are frequently characterized by abstraction, with truncated, elongated, or emphasized body parts, and a surface decorated with incised or painted geometric and abstract patterns. The figurines heightened sense of female corporeality has led some scholars to identify them as representations of a powerful mother goddess, whose relationship to earthly and human fertility is demonstrated in her remarkable, almost sexualized forms. The great variety of contexts in which the figurines are found, however, has led more recently to individualized readings rather than to a single, overarching interpretation. The set of 21 female figurines and their little chairs from Poduri-Dealul Ghindaru that is central to the exhibitions installation of this category of objects, for example, was found near a hearth in an edifice that has been interpreted as a sanctuary.

One widely accepted interpretation based upon its context, then, is that the figures represent the Council of Goddesses, with the more senior divinities seated on thrones. Others take a more conservative approach suggesting that the figurines formed part of a ritualistic activity – the specific type of ritual, however, remains open to interpretation. As The Lost World of Old Europe illustrates, the refinement of the visual and material language of these organized communities went far beyond their spectacular terracotta figurines. The technological advances made during this 1,500-year period are manifest in the copper and gold objects that comprise a significant component of this exhibition.

Gold and precious metals

The earliest major assemblage of gold artifacts to be unearthed anywhere in the world comes from the Varna cemetery, located in what is now Bulgaria, and dates to the first half of the 5th millennium BC. Interred in the graves are the bodies of individuals who may have been chieftains, adorned with as much as five kilograms of gold objects, including exquisitely crafted headdresses, necklaces, appliqus, and ceremonial axes. Indeed, it is in Old Europe that one sees the first large-scale mining of precious metals, the development of advanced metallurgical practices such as smelting, and the trade of objects made from these materials.

Old Europe trade

It is also important to note that these cultures did not live in isolation from one another, but instead formed direct contacts, most clearly through networks of trade. Gold and copper objects were circulated among these cultural groups, for example. The most striking material traded throughout much of southeastern Europe, however, is the Spondylus shell. Found in the Aegean Sea, Spondylus was carved into objects of personal adornment in Greece from at least the early Neolithic period forward. The creamy white colored shell is known to have been traded as far as the modern United Kingdom by the 5th millennium BC. Many of the most-common forms are on display in this exhibition and include elaborate beaded necklaces, tubular bracelets, and pendants or amulets. The shells can perhaps be read as markers of a common origin or as indicators of the owners elite position within society.

Pottery that lives up to modern standards

Within their homes Old Europeans stored an impressive array of pottery that has been methodically studied over the last hundred years by many southeast-European archaeologists. The diverse typologies and complex styles suggest that this pottery was used in household and dining rituals. Bold geometric designs – including concentric circles, diagonal lines, and checkerboard patterns – distinguish the pottery made by the Cucuteni culture, examples of which are featured in this exhibition. Part of the potterys allure is the resonance of its composition and design to a modern aesthetic. Indeed, one is easily able to envision a Cucuteni vessel displayed in a contemporary home.

Exhibitions at ISAW are not only meant to illustrate the connections among ancient cultures, but also to question preexisting and sometimes static notions of the ancient world. With The Lost World of Old Europe, New York University’s Institue of Study of the Ancient World desires to show that a rich and complex world can be found when looking beyond traditional and narrow definitions of antiquity, and indeed beyond standard depictions of the development of Western civilization.

You can still visit ‘The Lost World of Old Europe: The Danube Valley, 5000-3500BC’ until April 25th 2010 at the Institue of Study of the Ancient World at New York University. There’s no admission fee, so no excuse not to visit! Unless living far, far, far away but then you can still buy the book.

Egypts Minister of Culture, Farouk Hosni, and Zahi Hawass, Secretary General of the Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA), along with the governor of Luxor, Samir Farag, will embark today on an inspection tour along the Avenue of Sphinxes that connects the Luxor and Karnak temples. During this visit, they will install the piece of red granite that was returned to Egypt by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in its original place at the Ptah temple at Karnak.

Egypts Minister of Culture, Farouk Hosni, and Zahi Hawass, Secretary General of the Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA), along with the governor of Luxor, Samir Farag, will embark today on an inspection tour along the Avenue of Sphinxes that connects the Luxor and Karnak temples. During this visit, they will install the piece of red granite that was returned to Egypt by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in its original place at the Ptah temple at Karnak. The excavation team unearthed a large number of fragmented sphinxes that are now undergoing restoration efforts led by SCA consultant Dr. Mahmoud Mabrouk in order to be placed on the site.

The excavation team unearthed a large number of fragmented sphinxes that are now undergoing restoration efforts led by SCA consultant Dr. Mahmoud Mabrouk in order to be placed on the site.

Remains of one of the oldest members of the English royal family, Edith of England, have been unearthed at the

Remains of one of the oldest members of the English royal family, Edith of England, have been unearthed at the  The remains of a temple of Queen Berenike – wife of King Ptolemy III – have been discovered by archaeologists in Alexandria, Egypt.

The remains of a temple of Queen Berenike – wife of King Ptolemy III – have been discovered by archaeologists in Alexandria, Egypt.  Early studies on site revealed that the temples foundation can be dated to the reign of Queen Berenice – the wife of

Early studies on site revealed that the temples foundation can be dated to the reign of Queen Berenice – the wife of

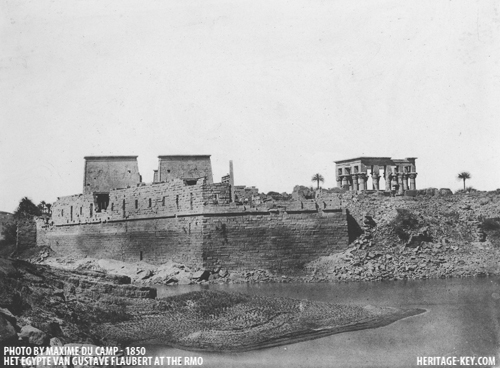

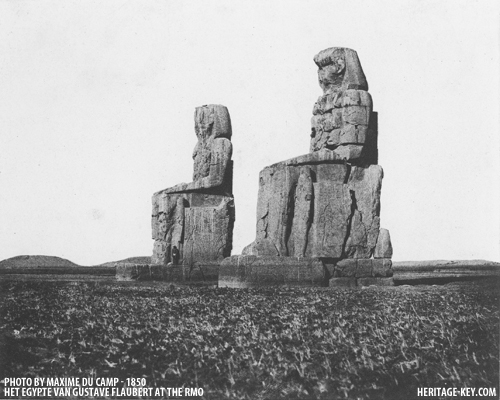

Gustave Flaubert – the author of ‘Madame Bovary’ – travelled through Egypt from October 1849 to July 1850. Together with his friend and photographer Maxime Du Camp he journeyed from Alexandria in the North to Sudan in the South and back. This journey is the focus of the exhibition ‘Het Egypte van Gustave Flaubert’ (Gustave Flaubert’s Egypt), which runs at the RMO in Holland until April 4th 2010. The expo follows the famous French writer on his journey through Egypt and takes its visitors from the amazing

Gustave Flaubert – the author of ‘Madame Bovary’ – travelled through Egypt from October 1849 to July 1850. Together with his friend and photographer Maxime Du Camp he journeyed from Alexandria in the North to Sudan in the South and back. This journey is the focus of the exhibition ‘Het Egypte van Gustave Flaubert’ (Gustave Flaubert’s Egypt), which runs at the RMO in Holland until April 4th 2010. The expo follows the famous French writer on his journey through Egypt and takes its visitors from the amazing

A splendid exhibition in New York – ‘The Lost World of Old Europe: The Danube Valley’ – brings to the United States for the first time more than 250 objects recovered by archaeologists from the graves, towns, and villages of Old Europe, a period of related prehistoric cultures that achieved a peak of sophistication and creativity between 5000 and 4000BC in what is now southeastern Europe.

A splendid exhibition in New York – ‘The Lost World of Old Europe: The Danube Valley’ – brings to the United States for the first time more than 250 objects recovered by archaeologists from the graves, towns, and villages of Old Europe, a period of related prehistoric cultures that achieved a peak of sophistication and creativity between 5000 and 4000BC in what is now southeastern Europe.

The 21st century has seen incredible advances in our knowledge and use of forensic sciences – to investigate crimes and to find out about people from ancient times. How can we apply this information to the people of ancient Egypt? Find out – and test your own skills in a hands-on practical session – at ‘

The 21st century has seen incredible advances in our knowledge and use of forensic sciences – to investigate crimes and to find out about people from ancient times. How can we apply this information to the people of ancient Egypt? Find out – and test your own skills in a hands-on practical session – at ‘