Channel 4’s Time Team has been excavating in the graveyard of a church in the village of Castor, Cambridgeshire and has come up with some compelling evidence that confirms the presence of a large Roman building. Known as the praetorium, the third century building is thought to have been the second largest Roman building in Britain.

Channel 4’s Time Team has been excavating in the graveyard of a church in the village of Castor, Cambridgeshire and has come up with some compelling evidence that confirms the presence of a large Roman building. Known as the praetorium, the third century building is thought to have been the second largest Roman building in Britain.

While the Time Team have not yet reached their conclusions, they have found a Roman mosaic pavement, the foundations of a very large building or set of buildings, which include Roman baths, as well as signs of Saxon occupation after the Romans withdrew from Britain.

Peterborough Today reported that the Time Team had uncovered a Roman mosaic pavement underneath some 17th century graves. Time’s Team’s presenter Tony Robinson was quoted as saying: The mosaic does seem to back up previous suggestions that there was a grand Roman building or set of buildings. The problem with Castor is that a lot of its history is a bit foggy and nobody knows the complete picture, but were hoping we will be able to contribute to a greater understanding about its past.

Tapping Local History Experts

Time Team’s development producer, Jim Mower, told me there had been several factors that led the team to that location, including conversations with a local expert on Roman history, Stephen Upex, author of The Romans in the East of England, as well as the drawings by the 19th century antiquarian Edmund Artis.

They learned about the mosaic floor by reading church records, which reported that grave diggers in the 17th century had had difficulty in digging down past a Roman floor (they had to bury a woman on top of the Roman floor). This happened again more recently when Peterborough City archaeologist Dr Ben Robinson was called to the church by grave diggers who had persevered for several hours in hacking through a Roman pavement in order to dig a trench, probably much to the disgruntlement of both the diggers and the archaeologist.

Time Team used modern techniques to test the theories of Mr Upex and also the drawings of Edmund Artis. Their aim was to try and establish the size and boundaries, if not the actual purpose, of the large Roman ‘praetorium’. Jim Mower said: “One of the challenges we faced was telling what was Roman and what was re-used Roman material. We had to get through the post-Roman layers, including burials from later centuries. It was very challenging because the archaeology was so complex.”

At the moment the archaeologists working on Time Team believe that the mosaic floor – an elaborate and well made mosaic – would have been the grand entrance to the building. The building, which has walls 1m thick, would have stood two or three storeys high. The team has not yet reached a conclusion on whether the praetorium was one large building/palace, or whether it could have been a complex of buildings.

Antiquarians at Castor

These findings confirm what archaeologists and local experts already knew. According to the Rev. William Burke, rector of the church of St Kyneburgha at Castor and also a member of the research committee of the Nene Valley Archaeological Trust, the Roman ruins at Castor have been described by several antiquarians including William Camden in 1612, William Stukeley in the 18th century and Morton.

Edmund Artis (buried in the church’s graveyard) was an agent of the local Fitzwilliam estate and he excavated the site in the 1820s in a methodical and, for that time, relatively scientific way. He came across the site while building roads and subsequently made several detailed drawings of the site.

The Rev. William Burke told me: People have always been aware of the presence of the Roman building at Castor, hence the name of the town today. The Saxons used the site to build a monastery and later the Normans used a large amount of stone from the Roman building to construct the church.

The Norman church, which contains Roman stone, is the one still on the site to this day. It is named after Saint Kyneburgha, who was the daughter of King Penda of Mercia and who founded a Saxon convent at the site in 650 AD. The Saxons named the site Castor after the Latin word Castrum, meaning a fortified Roman camp.

A Governor’s Headquarters?

The Rev. William Burke explained that the use of the so-called ‘praetorium’ (in this case meaning the governor of a Roman province’s residence or headquarters) at Castor is still not clear, although there have been several theories and suggestions over the years.

One supposition is that it was the residence of a Roman provincial governor during the third century AD. Castor would have been in Britannia Superior for most of the third century, then in the province of Maxima Caesariensis for most of the fourth century.

Another possibility is that the building was the headquarters of the Count of the Saxon Shore, a Roman military commander post possibly created by Constantine I during the fourth century AD, whose job it was to govern the military defences of the southern and eastern coasts of Britain from barbarian (Saxon) attacks. However, this is conjecture and there have not yet been any conclusive clues as to the identity of the building’s occupants and its purpose.

The Disappearing Roman Ruins

Little can be seen today of the Roman ruins in St Kyneburgha’s graveyard, but when the 17th and 18th century antiquarians visited the site, the Roman building was plainly visible above ground. Stukeley reports in the 18th century that 14 feet (about 4 metres) of the building stood above ground level. The stones from the building would have been ‘robbed out’, or removed, and reused as spolia in other local structures, including the present Norman-built St Kyneburgha church.

In fact, the presence of the Roman praetorium may well have been a contributing factor to St Kyneburgha’s impressive Norman tower. In a chapter on the history of the church published by the CAMUS project on local history, the Rev. William Burke suggests that the availability and proximity of a large quantity of worked stone may explain why a church in such a relatively small parish at that time (just 40 adult males recorded in the Domesday Book) should have one of Britain’s most impressive Norman towers.

A Prosperous Roman Community

St Kyneburgha church and its Roman structure are just a mile away from Durobrivae, a Roman fortified garrison at the village of Water Newton. Castor (not to be confused with Caistor) was in a prosperous Roman district connected by Ermine Street – Roman Britain’s artery road connecting York, Lincoln and London – and it was an area well known for the pottery it produced, which was known as Castor Ware.

The large Roman praetorium dates from 250 AD. However, there is a smaller, earlier structure thought to be a Roman villa, which dates from 60 AD. This would have been built at just around the time of Boudica’s revolt against the emperor Nero and governor of Britannia, Paulinus. In 250 AD, the Roman empire was in the midst of its ‘third century crisis’, during which it faced economic depression, disease and political conflict and fragmentation.

Time Team worked at the site from the 7th to the 11th of June. Their research project is ongoing and no conclusions have yet been drawn viewers will have to wait until the programme is screened (scheduled for Spring 2011) to hear their findings in full.

Photos courtesy of Time Team and the Rev. William Burke of St Kyneburgha Church of Castor.

Archaeologists in Mexico have uncovered a tomb inside a pyramid belonging to a king or high priest who died as many as 2,700 years ago. Three other bodies a woman also of high social status, a baby and young male adult were also found in the tomb inside the pyramid in

Archaeologists in Mexico have uncovered a tomb inside a pyramid belonging to a king or high priest who died as many as 2,700 years ago. Three other bodies a woman also of high social status, a baby and young male adult were also found in the tomb inside the pyramid in  Several different cultures lived in the region 2,700 years ago some of which would have interacted with each other, making it difficult to establish which culture the four individuals in the pyramid tomb represent although the team believe they are Zoque, an indigenous culture still living in

Several different cultures lived in the region 2,700 years ago some of which would have interacted with each other, making it difficult to establish which culture the four individuals in the pyramid tomb represent although the team believe they are Zoque, an indigenous culture still living in  There are more than 60 pyramids at Chiapa de Corzo, although about 30 per cent of them have been destroyed since the 1950s by local businesses. This was another factor that added some urgency to the excavation.

There are more than 60 pyramids at Chiapa de Corzo, although about 30 per cent of them have been destroyed since the 1950s by local businesses. This was another factor that added some urgency to the excavation. Very little information is available about what Chiapa de Corzo would have been like in 700 BC. Emiliano Gallaga Murrieta told me: The huge construction tells us this was a complex society and an important community. It occupied a geographically strategic path to the coast and would have had commercial and cultural interaction with central Mexico and Guatamala (as shown by the presence of jade in the pyramid).

Very little information is available about what Chiapa de Corzo would have been like in 700 BC. Emiliano Gallaga Murrieta told me: The huge construction tells us this was a complex society and an important community. It occupied a geographically strategic path to the coast and would have had commercial and cultural interaction with central Mexico and Guatamala (as shown by the presence of jade in the pyramid).

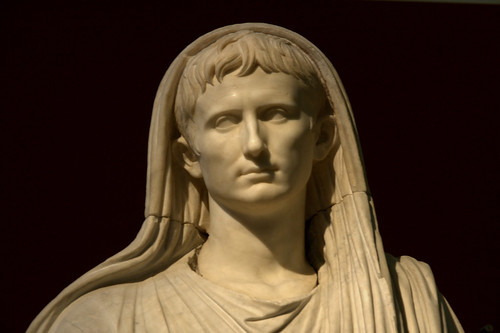

With his experience as head of a fledgling empire, security is one issue that Augustus takes very seriously. As emperor, instead of continuing the quest for expansion, Augustus reigned in the army, treated them well and ensured they were on his side. He recruited the Praetorian Guard from legions throughout the provinces ensuring widespread support.

With his experience as head of a fledgling empire, security is one issue that Augustus takes very seriously. As emperor, instead of continuing the quest for expansion, Augustus reigned in the army, treated them well and ensured they were on his side. He recruited the Praetorian Guard from legions throughout the provinces ensuring widespread support.