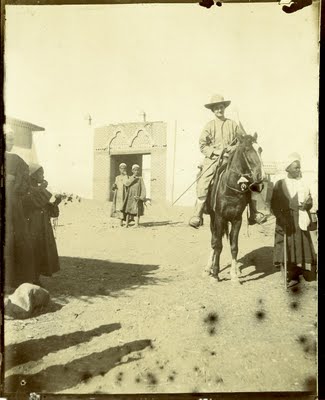

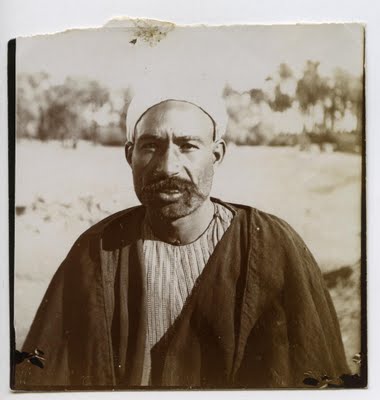

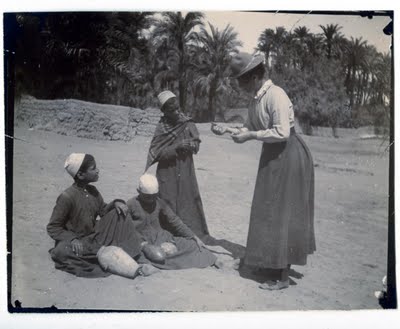

Unseen photographs by Flinders Petrie are now on temporary display in the Petrie Museum in London in an exhibition called Framing the Archaeologist: Portraits and Excavation. The photos were taken by Petrie on site in Egypt, featuring himself, his wife and the excavation workers, and offer a remarkable view of the early years of archaeology.

Unseen photographs by Flinders Petrie are now on temporary display in the Petrie Museum in London in an exhibition called Framing the Archaeologist: Portraits and Excavation. The photos were taken by Petrie on site in Egypt, featuring himself, his wife and the excavation workers, and offer a remarkable view of the early years of archaeology.

To mark the exhibition, the museum hosted an informal talk between Stephen Quirke and documentary maker Ayman El-Kharrat, entitled Workers and/or Archaeologists: In Conversation, questioning the status of Bedouin workers involved in early excavations in Egypt.

I went along to see what they had to say about this excellent archive of images, and the mysterious archaeologists portrayed in them.

The discussion centred on the subject of Quirke’s upcoming book Hidden Hands which will be published in May 2010. The book is the result of research he has done into the Egyptians who worked with Flinders Petrie on archaeological excavations from the 1880s to the 1920s. He questions how and why these people have been lost from the landscape of archaeological archives, and how their memoirs and records can be found.

Having returned himself from Egypt two weeks ago, Professor Quirke starts by saying he went there trying to re-connect to the past; what would it have been like in those days to work in an excavation site, to remove the artefacts first-hand from the soil?

Petrie was interested in people, in their social history; his writings on Lahun even portrayed him as an ethnographer. He recruited Bedouins from the Giza Plateau in 1882. At the time, Bedouins, or ‘Kuftis’ had only been in Egypt for around 100 years; they were originally from Tunis, and were different to Egyptian fellahin. In his notes, Petrie brands the kuftis as rascals and spies, before explaining why he chose them as part of his excavation team:

Among this rather untoward people we found however, as in every place, a small percentage of excellent men; some half-dozen were of the very best type of native, faithful, friendly, and laborious, and from among these workmen we have drawn about forty to sixty of two following years at Negadeh and at Thebes. They have formed the backbone of my upper Egyptian staff, and I hope that I may keep these good friends so long as I work anywhere within reach of them.

Among this rather untoward people we found however, as in every place, a small percentage of excellent men; some half-dozen were of the very best type of native, faithful, friendly, and laborious, and from among these workmen we have drawn about forty to sixty of two following years at Negadeh and at Thebes. They have formed the backbone of my upper Egyptian staff, and I hope that I may keep these good friends so long as I work anywhere within reach of them.

He also recruited Sudanese people to work in his Sinai excavation sites as they were more close to their own desert climate. Researching for any references to these people, Professor Quirke says there are none; the archives do not mention who went to the market or who cooked, and we cannot see the name of these people in printed publications.

Petrie was a mathematician, not an educated Egyptologist. There was no Egyptology chair before him, and we have to put his work in the context of other archaeological work done at that time by other European archaeologists to understand how he functioned. Petrie was much closer to the workers than most modern archaeologists.Professor Quirke finds in Petries personal letters bits of information not mentioned in his publications, such as when he writes to his wife (he was in Sinai, she was in Memphis), and complains about the mail not being delivered, either his own or the workers.

El-Kharrat comments that Petries understanding of social history being filled with passion as his finds are different from the ones at next doors museum’ (the BM). Professor Quirke elaborates on the European construction of knowledge and how it should be interesting to have Egyptian views too.

You have to go beyond pyramids, mummification and hieroglyphs to see daily life and its meaning. Did these Egyptians have academic training? What do we know about the life choices, opportunities, and skills of these people who worked in Egypt in excavation sites? There is also the issue of integrating Egyptian linguistics and literature with African and Arabic counterparts.

Things might be changing. El-Kharrat commented on the way the media, both Egyptian and Western, portray the work of these people. Professor Quirke stresses the need for European archives to link with the National Library in Cairo, and he also points out that the rigid construction of institutions of knowledge prevent many people to access knowledge as not everyone knows how to use a library.

Who showed Petrie where to dig for the Greek Papyri of el-Bahnasa? Some boy whose name we don’t even know. Petries manuscripts are a valuable source of information as they contain many side notes and records not included in the printed publications. There must be records done by the people who worked in these excavations; do they keep them at home?

As libraries cannot accommodate all the family records presented to them, many end up in peoples houses and pass on from generation to generation. Petrie relied on previous seasons excavation workers to train the next season’s workers.

Petrie was happy in the wilderness; he only came to big cities to deal with logistics; most of his time he was in the desert.

El-Kharrat comments that Petrie’s viewpoint was a colonizing one, and that his description of the way Egyptians lived is filtered by that view.

Is the self image of Egyptians a stable one? “Image is a changing field”, Professor Quirke replied, “as Egypt is still a key country between Arabic and African worlds.”

These touching images, however, seem to portray Egypt in its era of discovery in a series of fixed moments that can’t help but arrest the imagination of those who pay the exhibition a visit.