The life of Heinrich Schliemann is as legendary as the city he claimed to have discovered. A quintessential 19th century adventurer and amateur archaeologist, his obsession for Troy took him around the world and to Turkey and Greece. Fascinated by Homers epic narration, Schliemann stopped at nothing to discover the historical sites named by the poet. The veracity of his findings is however often questioned. Heinrich Schliemann: fanatic obsessed by his boyhood dreams or successful antiquarian?

A Boyhood Dream

Born in 1822 to a poor Protestant minister father and an unpublished literary critic mother who died when he was nine, Schliemann had a rag to riches life. Like many children of his time, he had to leave school at 14 to take up a job, selling herring and candles.

Despite this rather unscholarly beginning, Schliemann later argued that his interest in all things Greek and Homeric started with his father reading him the Illiad and Odyssey. Divergent explanations for his passion exist. According to a different, but also told by Schliemann, anecdote, his interest was born after hearing an older student reciting Homer verses. Even though the eventual result is the same, this variation already shows a key trait of Schliemanns personality: his capacity to adapt truth to his own interest.

Still according to his own anecdote, Schliemann announced he would discover Troy at the tender age of 8. Boyhood dream or lie carefully built to feed his own legend? In any case, in the 1830s, the city of Troy was eluding the most experienced archaeologists.

Ends to a Mean

Schliemanns love of history meant he wanted to see the world. Before his twentieth birthday, he boarded a steamer leaving for Venezuela as a cabin boy. Even though he never reached South America because of a shipwreck, it was indeed the beginning of a world tour. He took up positions in the Netherlands before being sent to Russia. During that time, in addition to developing his business talent, he improved his linguistic skills, learning his beloved Homers language, Greek. A gifted linguist, he was fluent in ten languages by the end of his life.

Even when not stationed on Homeric grounds, Schliemann was taking steps to get closer to his boyhood goal. In the 19th century, research and excavation scholarships were even less common than they are today so Schliemann needed to become rich before making any move towards Troy. Using his business knowledge as well as a good instinct for being at the right place at the right time, he was in California during the gold rush, just when it became American, making him a US citizen. After going back to Russia, he took advantage of the Crimean War to become an arms dealer. He also visited India and Corfu.

As is often the case with accounts of Schliemanns life, the official date of his retirement varies between a rather early 1858 or 1863. Again building his own legend, Schliemann explained in his memoirs that the only aim of his retirement was to pursue his wish of finding Troy. In the mid 1860s, he furthered his knowledge of the ancient world by enrolling at the Sorbonne in Paris in their Antiquity and Oriental Languages faculty.

Retracing Ulysses Steps

Fittingly, Schliemann started his archaeological life in Ithaca, a small island in the Ionian Sea of capital importance in Homeric myth. It is indeed the place where Ulysses is said to have lived before and after his Trojan adventures. Even though the current landscape does not match Homers description (the Odyssey says it is low-lying, far West and surrounded by the island of Doulichion and Same, whereas the island is mountainous and more Eastern than other Ionian Sea islands), Schliemann claimed to have found significant sites from the Odyssey there. This type of discrepancy between what Schliemann said and wanted and historical evidence is a recurrent characteristic of his work.

Hisarlik

Schliemann was not the type to enjoy a calm and eventless retirement or to be satisfied with a short stint at Ithaca. Having met Frank Calvert, who started excavations on the site of Hisarlik (or Hissarlik, both spellings are used), identified by Charles Maclaren in 1822 as the former location of Troy, he was sure that the place indeed held the key to Homers writings. In the Antiquity, tourists, sometimes famous such as Alexander the Great or Julius Caesar, already believed the place to be the site of the Trojan/Aegean war.

Situated in Turkey, Hisarlik, historically known as Illion is close to both the Aegean Sea and the Dardanelles, a location which matches Homers imprecise description of Troy. Furthermore, the place shows clear signs of ancient human occupation, not least because antique ruins were covered by a tell, this artificial mountain built by centuries of human presence.

Schliemanns claim that he had found Troy might have hold more to his own imagination and hopes than actual historical and scientific facts. Calvert, who Schliemann fell out with, argued that there was no remain from the period that should have been contemporary to the Trojan War on the site.

Priams Treasure

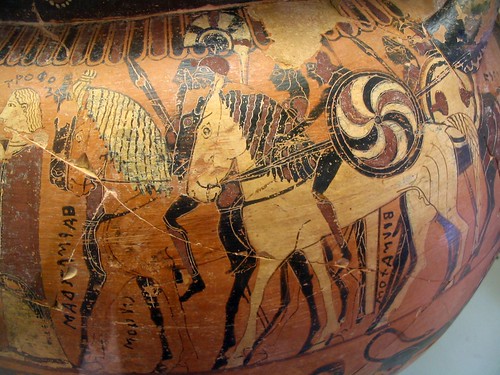

Disregarding those suggestions, Schliemann kept digging, taking every finding as proof that he was indeed excavating Paris city. For instance, upon discovering a stack of gold and other precious artefacts in May 1873, he claimed it was Priams treasure, Troys king at the time of the war. The treasure includes a copper shield and arms, gold cups and terracotta goblets.

In Homer, Priams son Hector is killed by Achilles. Thanks to Zeus and Hermes intervention and the kings plea, Achilles eventually returns the heirs corpse to the Trojans.

The role of gods in Priams story doesnt give his existence, or his treasure, much historical credential. After the discovery of the Manapa-Tarhunta letter, historians suggested Priam and Piyama-radu might have been one same person, a Hittite king who might have overpowered Troy. In any case, Homer specifies that the city was ransacked and set fire to after the Trojan horse episode, making the presence of a large amount of gold on the actual site harder to believe. Furthermore, archaeologist Carl Blegen, another Homer fanatic who studied the statigraphy of Hisarlik in the 1930s, showed that Priams Treasure was long posterior to the Trojan War.

Priams Treasure marked the end of archaeological search in the Ottoman Empire for Schliemann. He had smuggled parts of the Treasure out of the country. The government revoked his digging authorisation, jailed the official in charge of overseeing the excavation and sued the archaeologist. He later bargained part of the treasure against the authorisation to dig again.

Aside from the part returned to Turkey, exhibited at the Istanbul Archaeology Museum, the Treasure belonged from 1880 until the end of the Second World War to the Pergamon Museum in Berlin. It was then taken by the Red Army and has been on display at the Moscow Pushkin Museum since the end of the Cold War, as a compensation of historical destructions caused by the Nazis. Copies are on display in the Neues Museum in Berlin.

Controversy

As is the case with all myths, the veracity of Homers tales, not to mention his authorship, is somewhat disputed. In addition to soldiers from both Trojan and Achaen sides, the Illiad includes a fair share of mortals with superpowers, such as Achilles, and of gods tinkering with human destinies. Even if a battle might have taken place, as was often the case between Mediterranean peoples, it is unlikely that Homers words are to be taken at face value.

Historians have also suggested that Schliemann wasted his time by looking in Turkey, and that Homers epic tale might have been the synthesis of many inter-Greek battles. After the Second World War, long after Schliemann was dead, the American historian Carpenter favoured the possibility that rather than being a city, Troy was some sort of district, hence the use of the name Illion to refer to the location.

Theories about the real location of Troy are numerous. Some are more unlikely than others. Iman Jacob Wilkens, in Where Troy Once Stood, for instance argued that Troy was in fact located in England and was a Celt battleground, which would make Schliemanns digging entirely obsolete.

Whether or not it was the site of an antique battle, and whether or not the Trojan War even truly existed, Blegen showed that Hisarliks tell was made of 47 strata. The excavation of Troy VI, which should have been concomitant to the Trojan War, showed that the city walls had been destroyed by a natural disaster rather than an Aegean army. In Troy VII however, Blegen found corpses, arrows and evidence that buildings had been destroyed by fire.

Mycenae

In addition to Troy, Schliemann searched for Mycenae, another legendary Homeric city described as rich in gold. King Agamemnon, who lead the Achaens to Troy after Menelaus wife Helen was abducted by the Trojan Paris before being assassinated by his wife (or her lover, depending on the myth), was king if Mycenae.

When Schliemann reached the Greek city, excavations had already started under the leadership of soldier turned archaeologist Kyriakos Pittakis.

By 1874, when Schliemann undertook to complete the excavation of Mycenae, he was already convinced that the place was the city talked about by Homer. Rather than trying the ruins he found, he once again read every discovery as confirming his belief.

As announced by Homer, Schliemann discovered a lot of gold in the sites tombs. Since the location had never been systematically excavated, it is far from unusual and doesnt in itself prove anything further than the fact that the buried were rich, warriors (weapons were found alongside corpses) and probably powerful.

Schliemanns most significant discovery was a gold funeral mask, dubbed Mask of Agamemnon, which he found in 1876. Upon finding it, he allegedly felt he had gazed upon the face of Agamemnon, thus completing his boyhood search for traces of Homers epic tales.

Over the past decades however, historians have started to suggest that Schliemann, wishing to make reality resemble his desires, might have faked the mask. Known for contradicting himself in his writing, he also had a reputation for digging up artefacts in certain places before pretending he had found them elsewhere. The mask is so extraordinary in its craftsmanship, so different from the other found in Mycenaean grave shafts it is the only one in three dimensions, with facial traits cut out, detailed eyes that some have suggested that it can only be contemporary of Schliemann.

End of Life and Legacy

Only bad health could keep Schliemann away from his ruins. In 1890, at the age of 68, he had to stop digging to travel to Halle, in Germany, where he underwent an operation of his ear. Despite affirmations of the contrary at the time, the surgery was unsuccessful. His ear got in the way of him coming back to Athens in time for Christmas, but not in the way of him visiting other legendary ruins in Pompei, which he had already seen as a younger, healthier and less experienced archaeologist. He died in Naples on Boxing Day 1890. He is buried in the First Cemetery in Athens, in a temple-shaped mausoleum with a frieze showing his archaeological exploits. A fitting tribute for a man fascinated by Ancient Greeks.

Whether or not he discovered the real site of Troy, and whether or not this site and city ever existed, Schliemanns work contributed to the excavation and discovery of some of the most important ruins of the Greek antiquity. He specifically played a key role in learning about Bronze Age Greeks. Yet, all isnt well. Like many excavations undertaken in the 19th century, Schliemanns research sometimes harmed what he discovered rather than preserving it.

To this day, historians and public alike are fascinated by the story of the Trojan War. Hisarlik is a key destination on many tourist tours of Turkey, as is Mycenae in Greece. The Mask of Agamemnon is a central attraction at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens. Priams Treasure is still the object of negotiations between Germany and Russia.