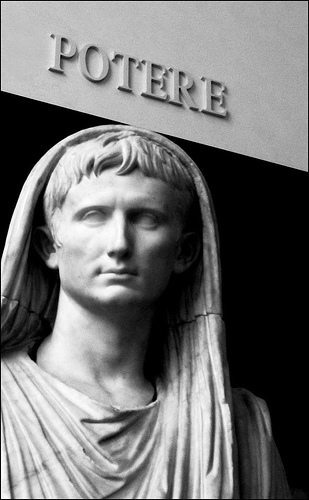

A new translation of a Roman victory stele, erected in April 29 BC, shows Octavian Augustus’s name inscribed in a cartouche (an oblong enclosure that surrounds a pharaoh’s name) – an honour normally reserved for an Egyptian pharaoh.

A new translation of a Roman victory stele, erected in April 29 BC, shows Octavian Augustus’s name inscribed in a cartouche (an oblong enclosure that surrounds a pharaoh’s name) – an honour normally reserved for an Egyptian pharaoh.

Octavian’s forces defeated Cleopatra and Mark Antony at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC. His forces captured Alexandria soon afterwards and Cleopatra committed suicide in 30 BC, marking the end of Egyptian rule.

Historians believe that although Octavian ruled Egypt after the death of Cleopatra, he was never actually crowned as an Egyptian pharaoh.

The stele was erected at a time when Octavian was still paying lip service to restoring the Roman Republic. He would not be named “Augustus” by the Roman Senate until 27 BC. In the years following that, he would gradually acquire more power.

New Translation of the Philae Victory Stele

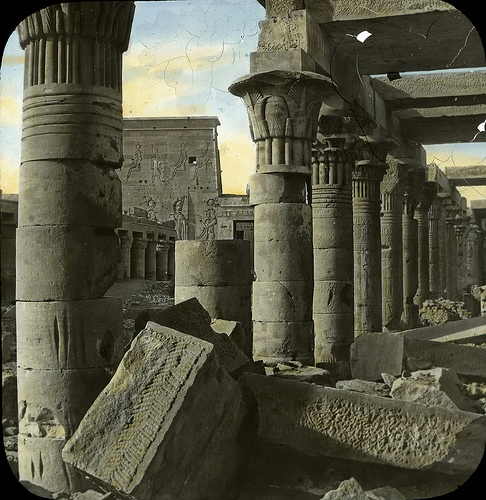

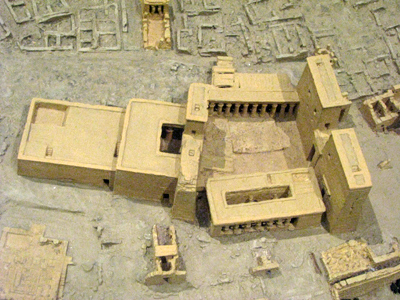

The victory stele is written in three languages – Egyptian hieroglyphics, Latin and Greek. It was erected by priests at the Temple of Isis at Philae, which is near the first cataract, the traditional border between Egypt and Nubia. The Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, Canada, has a physical model of Philae, a picture of which is being shown in this article.

The stele was commissioned by Gaius Cornelius Gallus, a Roman who was appointed to run Egypt as a province by Octavian. It celebrates the end of the Ptolemaic kings and the defeat of the “king of the Ethiopians.”

It has been known to scholars for about 100 years. However, the hieroglyphic writing is difficult to translate as the symbols are not clear on the stone. Previous work suggested that Gallus’s name had been written in a cartouche.

The new translation work was done by a team that includes Professor Martina Minas-Nerpel of Swansea University in Wales. They recently published a book, The Trilingual Stela of C. Cornelius Gallus from Philae, but are unable to release a picture of the stele at the moment.

Professor Minas-Nerpel gave a presentation at the University of Toronto recently and Heritage Key interviewed her afterwards. Minas-Nerpel said that there should be no mistake – on this victory monument Octavian was certainly given treatment reserved for a pharaoh.

“The name of Octavian is written in a cartouche – he’s treated as any other Egyptian king,” she said.

The translation certainly sounds like it’s for a pharaoh. Here’s a snippet:

Regnal year one, 4th month of the winter season day 20 (16 April 29 BC) under the majesty the Horus, the perfect child, mighty arm ruler [of rulers] chosen of Ptah Kaisaros (Octavian) living forever….

How Does a Roman Emperor Become a Pharaoh?

So the question is why was Octavian named as pharaoh in this inscription? Historians don’t believe that he was ever crowned as the Pharaoh of Egypt.

Professor Minas-Nerpel believes that it wasn’t Octavian who insisted on having this honour, instead it was Egyptian priests. For 3,000 years there had been an Egyptian pharaoh, they could not simply do away with the position.

“They had to have an acting pharaoh – the only acting pharaoh (possible) under Octavian was Octavian,” she said. “The priests needed to see him as a pharaoh otherwise their understanding of the world would have collapsed.”

Of course that’s not to say that Octavian didn’t condone the idea on some level. He needed Egypt’s grain and to get access to it he needed the Egyptian people to not rebel against him.

“He needed to have a calm province and the key element to keeping the province calm were the priests – they were key to the population,” said Minas-Nerpel.

“The priests needed to see him as a pharaoh otherwise their understanding of the world would have collapsed.”

This stele would not be the only time Roman rulers had their names written in a cartouche. Minas-Nerpel said that there are examples of Roman Emperors having their names written in that form as late as the 3rd century AD. She also said there is one other example of Octavian’s name being written in a cartouche – a gateway on the island of Kalabsha in Southern Egypt – that also appears to date to on or shortly after 30 BC.

The Downfall of Gaius Cornelius Gallus

Gaius Cornelius Gallus was a soldier, administrator and poet – he wrote four books of poetry dedicated to a mistress named “Lycrois.” Despite the fact that Gallus was not a senator, Octavian turned to him to rule Egypt after Cleopatra committed suicide in 30 BC. Gallus administered Egypt until he was recalled to Rome in 27 BC. The Roman writer Cassius Dio wrote in the 3rd century AD that:

Cornelius Gallus was encouraged to insolence by the honour shown him. Thus, he indulged in a great deal of disrespectful gossip about Augustus and was guilty of many reprehensible actions besides; for he not only set up images of himself practically everywhere in Egypt, but also inscribed upon the pyramids a list of his achievements.

Cornelius Gallus was encouraged to insolence by the honour shown him. Thus, he indulged in a great deal of disrespectful gossip about Augustus and was guilty of many reprehensible actions besides; for he not only set up images of himself practically everywhere in Egypt, but also inscribed upon the pyramids a list of his achievements.

The new translation of the victory stele shows that Gallus treated Octavian with respect, but that he wasn’t afraid to brag about his own accomplishments. One part of the stele reads that he was:

First prefect of Alexandria of Egypt, vanquisher of the Theban insurrection with(in) fifteen days.

He also says on the monument that he defeated an army in Nubia:

After the army was lead beyond the Nile cataract, after envoys of the king of the Ethiopians were heard near Philae and after this king was received into custody… (Gallus) gave a donation to (the) hereditary gods and Nile helper.

If that wasn’t enough Gallus had himself drawn onto the stele. He is shown riding a horse, about to slaughter what looks like an enemy soldier.

This sort of bragging may have been his undoing in the long run. Minas-Nerpel said that Octavian would not have wanted it advertised that there were rebellions in Egypt that needed to be put down by Gallus.

“Presumably he (Gallus) was to powerful and he didn’t sort of give enough respect to Octavian – that might have been the reason,” she said. Cassius Dio records what happened after he was recalled to Rome in 27 BC:

He was accused by Valerius Largus, his comrade and intimate, and was disfranchised by Augustus, so that he was prevented from living in the emperor’s provinces. After this had happened, many others attacked him and brought numerous indictments against him. The senate unanimously voted that he should be convicted in the courts, exiled, and deprived of his estate, that his estate should be given to Augustus, and that the senate itself should offer sacrifices. Overwhelmed by grief at this, Gallus committed suicide before the decrees took effect.