The burial chamber is the only room of Tutankhamun’s tomb which was decorated. The early and unexpected death of the young king left little time for preparation and, from the modest size and arrangement it is clear that this is a hastily converted commoner’s tomb not intended for a royal burial. Despite the sparsity of mural paintings in King Tut’s tomb, they are an essential part of the funerary process, and should not be overlooked.

Funerary Rituals

For a Pharaoh, and indeed for Egyptians in general, life was a preparation for death, the Afterlife and immortality. The ceremonies of burial and the decoration of the tomb provide the religious rituals, spells, incantations and directions by which the Pharaoh would first be reunited with his body and spirit, then face judgement before passing through the Netherworld to be welcomed into the Afterlife as an immortal being.

For a Pharaoh, and indeed for Egyptians in general, life was a preparation for death, the Afterlife and immortality. The ceremonies of burial and the decoration of the tomb provide the religious rituals, spells, incantations and directions by which the Pharaoh would first be reunited with his body and spirit, then face judgement before passing through the Netherworld to be welcomed into the Afterlife as an immortal being.

These three phases are represented as three distinct ceremonies, which are portrayed in the paintings on the wall. In the first, the dead king must be borough back to life in the ceremony of The Opening of The Mouth. He is then judged for his suitability to enter the Afterlife in the ceremony known as The Weighing of The Heart and finally, he is welcomed as an immortal if he can successfully navigate the perils of the Netherworld.

These beliefs, and the time available, determined the extent of the ritual support provided to the Pharaoh from the wall paintings in his tomb and burial chamber which, in Tutankhamun’s case, were quite meagre.

Reading the Walls

Colour played an important role in tomb paintings, and images were based on a surprisingly limited palette. White represented purity, power and greatness; black represented death and the night, red represented life, victory and anger, yellow was often used to represent gold and the eternal life of the sun god. Blue represented water, the sky, fertility and re-birth, and green was the colour of vegetation and represented new life. The walls of the burial chamber all have a rich yellow background indicating eternal life.

The paintings should be read from right to left in a sequence starting with the East Wall which is to your right as you enter the burial chamber. As a convention, depictions of mortals have the face looking left and those of gods look to the right.

East Wall – The King’s First Journey

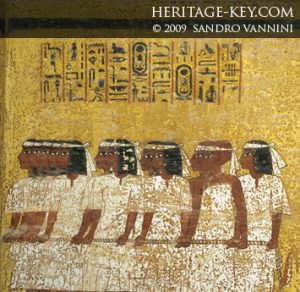

The east wall depicts the funeral procession, with the King being pulled on a sled to his tomb. The twelve people hauling the sledge are high court officials depicted wearing the white sandals and headbands worn for sacred ceremonies. There are several groups of people depicted, including Ay, the king’s successor, Maya, the King’s Treasurer, General Horemheb, who would shortly succeed the ageing Ay, two visors and a number of High Priests. This group of envious courtiers, jealous priests and ambitious successors would have made for an explosive mix of religion, death, resurrection, money and power.

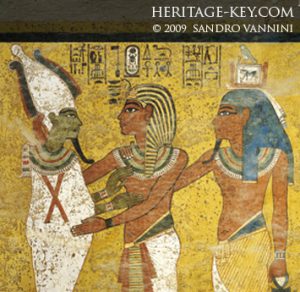

North Wall – Three Rituals

The North Wall depicts three important rituals – the Opening the Mouth ritual, the reincarnation or resurrection of the king, and the final ritual in which Tutankhamun and his life-force or spirit embraces Osiers, patron of the Underworld and the dead.

Throughout the height of Egyptian civilization, Osiers was the primary deity. In power, he was second only to his father, Ra, and was the leader of the gods on earth. The spells and rituals cast by Isis, plus many others given to the people by the gods over the centuries, were collected into The Book of Going Forth by Day, colloquially known as The Book of The Dead.

In the underworld, Osiers sits on a great throne, where he is praised by the souls of the just. All those who pass the tests of the underworld become worthy to enter The Blessed Land, that part of the underworld that is like the land of the living, but without sorrow or pain. In addition to the judging of the Heart, Osiers passes final judgement over the dead.

The young king is now ready to face the challenges of the Netherworld.

West Wall – the Baboon Guards

The West Wall is dedicated to the first hour of the night and scenes from the book of My-ducat or What is in the Netherworld. This wall, along with the magical text from the Imy-duat, is the king’s guide and safe passage through the Underworld which he must successfully navigate if he is to reach the Afterlife.

The West Wall is dedicated to the first hour of the night and scenes from the book of My-ducat or What is in the Netherworld. This wall, along with the magical text from the Imy-duat, is the king’s guide and safe passage through the Underworld which he must successfully navigate if he is to reach the Afterlife.

In the top left we see the solar boat, to be used by the king on his journey, in which rides Khepri, the god associated with the dung beetle, whose behaviour of maintaining spherical balls of dung represents the forces which move the sun.

Khepri was considered as an embodiment of the sun itself, and therefore a solar deity. Two male figures, representing the god Osiris, raise their arms to Khepri in homage whilst, top right, five deities prepare to assist Tutankhamun in his journey through the underworld and the night. A successful navigation of the Underworld will allow Tutankhamun to be welcomed into the Afterlife as an immortal.

South Wall – The God-King

The king, having successfully travelled through the underworld, is welcomed to the Afterlife by Anubis, on the left, the jackal-headed god of embalming, and, on the right, the life giving Hathor, goddess of the west. A third figure, destroyed when Carter opened the burial chamber, shows Isis, the goddess of simplicity from whom all beginnings arise. Tutankhamun, who is now immortal, will begin the life-giving daily ritual.

Contrary to popular belief today, the Pharaoh was not a god in and of himself. He was a god-king, an avatar, not an incarnation, and there is a subtle difference. The Pharaoh was believed to have the spirit of Horus, son of Osiris, residing within him and guiding him along the proper path of Maat. He also had the spirits of all his predecessors who dwelt with Osiris in the afterlife to aid him. Yet even with this he was not deemed infallible, for they would only support him so long as he upheld Maat.

When the Pharaoh died his spirit joined those of his predecessors together with Osiris. From there he guided his successors as he had been guided in life. Thus a continuous cycle was set up: the living honouring and remembering the dead, and the dead aiding the living from the afterlife. All of this is connected through the Pharaoh, who is the emissary of both worlds and the link between Life and Death.

Kept by Their Fate

The wall paintings and incantations used in the tombs of the Valley of the Kings represent the profound belief of the ancient Egyptians in the link between life and death and in death as a continuation of life, with the dead responsible for maintaining the cycle of life and death and for the well-being of the living. Such beliefs go to the heart of the general stability which was such a notable factor in the three thousand year empire of Ancient Egypt. It was only when these beliefs were shattered that the Egyptian Empire began its inevitable decline.