Dr Stephen Quirke is a lecturer of Egyptology at University College London, and curator of the Petrie Museum, named after the famous archaeologist William Flinders Petrie. Dr Quirke has written several books on Ancient Egypt; his main areas of interest being history of the state/institutionalisation; gender; Egyptian language; museology; and ethics in archaeology and anthropology. Heritage Key caught up with Dr Quirke to discuss the recent Egyptological Colloquium, the merits of smaller museums such as the Petrie, and his own fascination with the area.

HK: What initially attracted you to the study of Ancient Egypt?

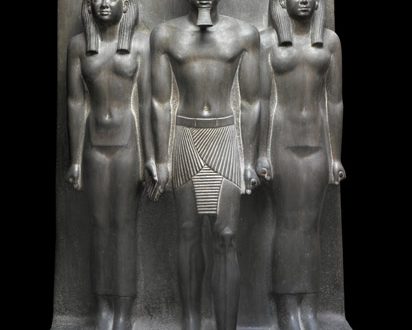

SQ: The monumental displays in the Sculpture Gallery of the British Museum.

HK: Do you feel the Egyptian government has any right to demand the repatriation of objects such as the Rosetta Stone?

SQ: Yes though I feel that restitution is too reactive, media-bound and focussed on the monumental, and I think that it is likely to develop in more interesting directions in the coming decades as Egyptian Egyptology replaces European Egyptology as the driving-force of the discipline.

HK: Were you generally pleased with how the Egyptological Colloquium went? Do you think there was enough debate present?

SQ: The Book of the Dead Colloquium was an exceptionally strong gathering of researchers on the topic, with a welcome number of younger researchers and students, to show the vibrancy of the field. As most often, informal discussions during the days were, for myself, the most rewarding opportunities for debate.

HK: Was there anyone in particular whose work you were most impressed with?

SQ: Difficult to select one name: the presentation by Irmtraut Munro was yet another astonishing example of sheer energy in assembling a document reduced to fragments and scattered among many collections, and then, in its reassembled condition, overturning many specialist assumptions, in this instance about the history of the Book of the Dead in the Late Period (with a sequence thought to originate in Memphis, now attested in Thebes a century earlier).

HK: Were you pleased with the way your work (on the phenomenon of invention in the Book of the Dead) was received? What inspired you to write it?

SQ: I need to publish an idea and read its reception in publications by others, to assess its impact: print publication is still the essential medium for constructing and circulating and revising scientific knowledge, including historical knowledge.

My work was most recently inspired by joint work with Dr Gianluca Miniaci of Pisa, on a particular late Middle Kingdom burial-group from which the finds are preserved in the Egyptian Museum Cairo, and the relation with the concept of the tomb in that period.

HK: Did you agree with Dr John Gee that the Book of the Dead can be seen as a canon? Do you think there are any valid comparisons with the Christian Bible?

SQ: I found the arguments put forward by Dr John Gee very interesting, and am broadly sympathetic to the approach. I would like to see more research into a specific difference, between works stated to be completed and those apparently more fluid; in this regard, the paper by Malcolm Mosher on the conscious remodelling of old compositions is of particular importance, as it shows a different notion of received compositions as being more malleable than we are used to thinking of for sacred, or indeed more broadly any literary writings.

HK: Do you believe there are enough large forums such as the Colloquium catering for the study of Ancient Egypt?

SQ: Difficult: on the one side, there are endless topics to be discussed; on the other, there are already numerous occasions for meeting, often making it difficult to attend the conferences and symposia already on offer. If I had to choose a single answer, I would probably have to say yes to this question.

HK: What do you feel a smaller museum like the Petrie can offer that a large one like the BM can’t?

SQ: Two points specifically are different, notwithstanding the similarity in content:

Firstly: visitors, including researchers, exercise their eyes and minds in an astonishingly different way even when looking at exactly similar objects in the two different institutions – simply the presence (a) of the colossal and (b) of a large public introduces a dominant ethos of Monument for a British Museum visitor, which, unfairly, is then perceived as not containing domestic material; by contrast, the Petrie Museum, as a university museum, may be able to discuss certain debates without the heavy political weighting imposed on a national collection – debates regularly taught in Museum Studies and History courses in universities, such as restitution, the ethics of removing material from the ground, interracial relations, or the class struggle in archaeology – in practice the British Museum may be better at hosting these debates, or do it more often, but in perception the public perception of the two institutions may, again unfairly, allow the Petrie Museum, if it decides to, to pursue difficult debates without the same level of assumptions by the public attending.

Secondly: at 80,000 antiquities, the Petrie Museum is probably at the limit of the size a collection can be without breaking it up into separate departments – as a result, it presents a unity covering the different chronological, linguistic and religious dimensions of Egypt – Prehistory, Ancient Egypt (or ‘Pharaonic Egypt’), Hellenised Egypt (or ‘Greek and Roman Egypt’), Coptic Egypt and Muslim Egypt – that unbroken unity can, under a dedicated management, create different grounds for displays, visits and regular museum practice.

HK: What improvements would you make to the way ancient artefacts are displayed in museums today?

SQ: one basic change I would welcome would be to share specialist knowledge about objects in a more dynamic and reflective way, linking the museum visitor to people in other places, above all the people in the landscape where the exhibits were found, and people with different interests and opinions – that might help make museum displays more relevant to life.