Attribution: Heritage Key Cairo Egypt Key Dates This item is dated from the 4th Dynasty of the Old Kingdom. Key People The triad depicts King Menkaure, the last Great Pyramid builder. The 17th Nome of Upper Egypt and the goddess Hathor are pictured to the left and the right of Menkaure respectively. In the Triad of Menkaure, King Menkaure is depicted in the foreground wearing the white crown of Upper Egypt. Hathor, the goddess of music and love, is shown to the right of Menkaure, holding his hand. To the left of Menkaure is the 17th Nome of Upper Egypt.…

-

-

The cemetery at Saqqara is one of the most important archaeological sites in Egypt. Over six kilometres long, it boasts thousands of underground burial sites, as well as the six-step Djoser pyramid – Egypt’s oldest pyramid. The ruins at Saqqara have long attracted the interest of explorers, grave-robbers and local people. Travellers first reported evidence of antiquities at Saqqara in the 16th century. The Djoser Pyramid and the smaller pyramids around it were hard to miss – but the size of the necropolis only became apparent with the advent of excavations in the 19th century. It was not until Napoleon…

-

Dr Stephen Quirke is a lecturer of Egyptology at University College London, and curator of the Petrie Museum, named after the famous archaeologist William Flinders Petrie. Dr Quirke has written several books on Ancient Egypt; his main areas of interest being history of the state/institutionalisation; gender; Egyptian language; museology; and ethics in archaeology and anthropology. Heritage Key caught up with Dr Quirke to discuss the recent Egyptological Colloquium, the merits of smaller museums such as the Petrie, and his own fascination with the area. HK: What initially attracted you to the study of Ancient Egypt? SQ: The monumental displays in…

-

It’s long been a common stereotype that Akhenaten was a pacifist, someone who avoided warfare when possible. If you read Heritage Key’s article on Nazi Egyptology you will see that the Nazis hate him for that precise reason. But recent research, presented this weekend at an Egyptology symposium in Toronto, shows that the Amarna leaders – including Akhenaten, King Tut and Nefertiti – all supported a sizable fortress in the Sinai desert. Located at Tell el-Borg it was a formidable bastion. It was 120 meters east-west by 80 meters north-south. The walls were four meters thick (at the base) and it…

-

On September 19, 2009, the American Research Center in Egypt, Pennsylvania Chapter (ARCE-PA) held its symposium on the joint Expedition to Abydos, Egypt, fielded by the University of Pennsylvania, Yale University, and New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts. This long-term project based in Egypt’s most ancient royal burial grounds includes some of the most prominent Egyptologists in the field today—Dr. David O’Connor, Dr. Matthew Adams, Dr. Janet Richards, Dr. Josef Wegner, and Dr. Stephen Harvey. I was able to reach Dr. O’Connor prior to the symposium for an exclusive interview. Dr. O’Connor offered his experience and insights on such subjects as…

-

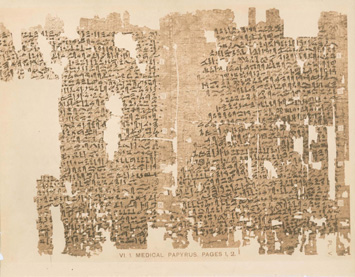

The Edwin Smith Papyrus was this year touted as “the birth of analytical thinking in Medicine and Otolaryngology,” in the medical journal The Laryngoscope. Along with a collection of other fascinating papyri, the script gives an incredible insight into the knowledge, skills, and procedures of ancient Egyptian medicine, and offers some tips on how to treat trauma issues, such as a man with a massive gouge in his head. Much of what we know about Egyptian medicine comes from roughly a dozen medical scrolls that have survived. The oldest one is the Kahun Scroll, dating to 1820 BC, which focuses in Gynaecology. The two…

-

Key Dates 330 BC This wooden cult statue of Osiris dates from the Ptolemaic period, around 332-330 BC. One of the most interesting aspects of this life size statue of the god Osiris is that it was quite likely used as a cult statue for worship. It is in wood, finished with plaster or gesso, and was painted; originally, the body of the god was wrapped in linen bands exactly like an Egyptian mummy, so that the statue showed the entombed Osiris as god of the dead or of the afterlife. The eyes are inlaid with glass and stone, giving…

-

Key Dates 650 BC Created during the Late Period of ancient Egypt (c 700-600 BCE) This Etruscan black bucchero ware tray was made during the late 7th or early 6th century BC. Bucchero is a style of black ceramic pottery made shiny by polishing. The tray is decorated with human heads. Origin & Collection On display at: The Hunterian Museum Images Put your Flickr photos of this object into the Heritage Key group, and tag them with keyobject-1701, to see them here!

-

Key Dates 1186 BC The papyrus dates from the XX Dynasty of Ancient Egypt, which lasted from 1186-1069 BC. It was discovered in the early 19th century. Key People It was probably created by a painter from Deir El-Medina village. When French scholar (and translator of the Rosetta Stone) Jean-François Champollion viewed the papyrus in Torino in 1824, he described it in his notes as: “an image of monstrous obscenity that gave me a really strange impression about Egyptian wisdom and composure.” Key People: Jean-François Champollion The Turin Erotic Papyrus is a famous (or rather, infamous) 12th/11th century BC Egyptian…

-

The question of how the Great Pyramid of Giza was built is one of the most hotly-debated topics in ancient history. Maverick French architect and self-styled “Mr Pyramid” Jean-Pierre Houdin is determined that he has the answer – the the 4,569 year-old monument was, he argues, erected from the inside-out, using an internal ramp built into the fabric of the structure. Others are skeptical of his theory, but Houdin is certain he has the proof. Here he gives some exclusive insights into his life and work (a decade-long obsession), launches a broadside at the Egyptology fraternity that he feels still…