The recent reopening of Berlin’s Neues Museum has brought back into the limelight one of the ancient world’s greatest treasures. Yet as Thutmose’s masterful Bust of Nefertiti takes centre stage in Germany’s latest collection, the woman behind Egypt’s most famous sculpture remains a conundrum. Heresies, lost kingdoms and mysterious kingships have made Nefertiti more than the ‘most beautiful woman in the world’. But who was she, and how did she become one of the greatest leaders in Egypt’s history?

The recent reopening of Berlin’s Neues Museum has brought back into the limelight one of the ancient world’s greatest treasures. Yet as Thutmose’s masterful Bust of Nefertiti takes centre stage in Germany’s latest collection, the woman behind Egypt’s most famous sculpture remains a conundrum. Heresies, lost kingdoms and mysterious kingships have made Nefertiti more than the ‘most beautiful woman in the world’. But who was she, and how did she become one of the greatest leaders in Egypt’s history?

Nefertiti’s origins are a mystery. Born some time around 1370 BC, theories abound that she was the daughter of army general Ay, who would go on to become pharaoh. Though there is no direct link between the two, Nefertiti’s sister Mutnojme features heavily in Ay’s tomb, in the Valley of the Kings. Yet it is unlikely Ay sired Nefertiti, if at all, with his chief royal wife Tey, who is called ‘governess’ or ‘nurse’ of Nefertiti rather than the conventional motherly title of ‘royal mother of the king’s chief wife’. Another claim states Nefertiti was the daughter of Queen Tiye, wife of Amenhotep III, the father of her future husband Amenhotep IV (Akhenaten). This would make Nefertiti and her future husband siblings, though it isn’t an uncommon phenomenon in Egyptian history.

Nefertiti continued her upbringing in obscurity, not appearing in any records until, aged just 15, she married the teenage king Amenhotep IV – himself a boy of just 16. Together the duo would change the face of their empire’s history, building one of its biggest cities and reinventing its religion. Yet Nefertiti, meaning ‘the beautiful one has arrived’, had to share her beloved husband with three other wives: Mekytaten, Ankhesenpaaten and Kiya. The latter of the trio is believed to have been the mother of Smenkhkare and Tutankhamun, the king’s successors (though King Tut’s parentage is the subject of fierce debate in itself).

The Chief Wife

Nefertiti, however, took the lead role of Chief Royal Wife, the object of a deep affection from her husband. During their lives together, she bore him six daughters. Their eldest, Merytaten, is even thought to have become his wife during later years. The king would bestow great respect on all his wives, yet it was Nefertiti whose image adorned his huge sarcophagus, and who would be pictured most often alongside him, holding their children and kissing him in public.

Nefertiti, however, took the lead role of Chief Royal Wife, the object of a deep affection from her husband. During their lives together, she bore him six daughters. Their eldest, Merytaten, is even thought to have become his wife during later years. The king would bestow great respect on all his wives, yet it was Nefertiti whose image adorned his huge sarcophagus, and who would be pictured most often alongside him, holding their children and kissing him in public.

Nefertiti, however, was more than a wife to Amenhotep. In the fifth year of his reign as the 12th king of the 18th Dynasty, he and Nefertiti instigated a paradigm shift in the empire’s traditions never seen before or since. Changing his name to Akhenaten, meaning ‘effective spirit of Aten’, the king discarded Egypt’s complex polytheistic beliefs in favour of worshipping Aten, the sun disc. Aten was the only life-giving force, its rays shining down only on the royal family. Thus Egyptians had to worship the king and queen, something which is thought to have divided Egypt. Akhenaten also moved Egypt’s capital city from Thebes to Akhetaten (more commonly known by its modern name Amarna), a completely new city some 200 miles north. The era would become known as the ‘Amarna Period‘, and would go down as the most controversial in Egypt’s history. Akhenaten would be known as the ‘heretic-king’; his radical beliefs and residence all-but wiped out after his death.

Akhenaten’s Eyes

Yet many claim Nefertiti was pulling the strings behind her husband’s momentous rule. She too changed her name, to Neferneferuaten-Nefertiti; ‘Aten is full of radiance because the beautiful one has arrived’. She was a high priestess of Akhenaten’s religion, and only through the combination of the pair could Aten’s power be spread across the nation. It is also a widely-held belief that Akhenaten was disabled, and may have had bad eyesight. Several populist accounts paint the picture of a man who, while great, needed the love and power of Nefertiti to carry out his ideas.

The greatest evidence backing Nefertiti as much more than a mere consort is the vast number of artefacts depicting the royal couple. The Amarna Period was one of immense artistic shifts as well as religious, with popular images of Akhenaten showing his wiry and conceptualised frame (known as the ‘grotesque’ movement) in contrast with the faithful and athletic reproductions of his predecessors. Traditional portrayals of king and queen had shown the pharaoh larger and more prominent than his queen. Yet not only did Nefertiti adorn twice as many reliefs in the first five years of Akhenaten’s reign, she also appears just as tall and powerful as her husband, if not more so. She even appears in the traditionally male pose of smiting her enemies.

The greatest evidence backing Nefertiti as much more than a mere consort is the vast number of artefacts depicting the royal couple. The Amarna Period was one of immense artistic shifts as well as religious, with popular images of Akhenaten showing his wiry and conceptualised frame (known as the ‘grotesque’ movement) in contrast with the faithful and athletic reproductions of his predecessors. Traditional portrayals of king and queen had shown the pharaoh larger and more prominent than his queen. Yet not only did Nefertiti adorn twice as many reliefs in the first five years of Akhenaten’s reign, she also appears just as tall and powerful as her husband, if not more so. She even appears in the traditionally male pose of smiting her enemies.

In fact there is little to separate the couple in many examples of Amarna art. Arguably the most famous of all, the ‘house altar‘ now also starring in the Neues collection, shows Nefertiti and Akhenaten with three of their daughters, receiving Aten’s rays. Nefertiti sits much more authoritatively than her husband, cradling two children to his one. Akhenaten’s pot belly and frail frame, a feature of his depiction, are also used to promote the previously mentioned views that he was handicapped, and may have suffered some genetic flaw, such as Marfan Syndrome; a complication causing thin, elongated limbs (weirdly, a modern drug prescribed to Marfan sufferers is called Atenolol)

Eulogies to Nefertiti appear to show her importance to Akhenaten, if not necessarily the entire Egyptian population. This is an example from Akhenaten’s boundary stelae at Amarna:

And the Heiress, Great in the Palace, Fair of Face,

Adorned with the Double Plumes, Mistress of Happiness,

Endowed with Favours, at hearing whose voice the King rejoices,

the Chief Wife of the King, his beloved, the Lady of the Two Lands,

Neferneferuaten-Nefertiti, May she live for Ever and Always

Nefertiti’s fashion even began to reflect her status. She wore a provocative clinging robe with a loose red sash. This imitated the clothing of pre and post-Amarna chief queens, who were known as ‘God’s Wife’. Some say her exotic dress was meant to maintain a constant state of arousal: Akhenaten’s new religion focused heavily on the importance of femininity in the eyes of Aten. Each of his wives had their own temple with no roof, so they could receive all of Aten’s love. She would later begin wearing the mortar-shaped headdress, which she wears on her famous bust. This allowed Nefertiti to embody Tefnut, the goddess of air and moisture. Thus, equal with her husband, Nefertiti, the goddess, channelled Aten’s power to her people.

The King of Egypt?

Yet just like the religion she worked so hard to introduce, Nefertiti would vanish from records around the 14th year of her husband’s reign. Egyptologists first thought she had fallen into disgrace with her king. Yet the images they had attributed to her, defaced and replaced with that of Merytaten, were later found to belong to Kiya. The simplest reason is that Nefertiti died suddenly, aged between 30 and 40. This fits both with her estimated age of death, and with theories that the Amarna Period collapsed largely due to the outbreak of illness – perhaps an early bout of plague.

Yet just like the religion she worked so hard to introduce, Nefertiti would vanish from records around the 14th year of her husband’s reign. Egyptologists first thought she had fallen into disgrace with her king. Yet the images they had attributed to her, defaced and replaced with that of Merytaten, were later found to belong to Kiya. The simplest reason is that Nefertiti died suddenly, aged between 30 and 40. This fits both with her estimated age of death, and with theories that the Amarna Period collapsed largely due to the outbreak of illness – perhaps an early bout of plague.

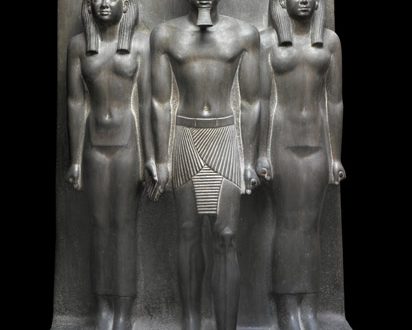

However there may be a more spectacular twist in Nefertiti’s tale. In his final two years, Akhenaten ruled as a co-regent with a mysterious pharaoh called Neferneferuaten. There is some evidence, and much more speculation, suggesting Nefertiti was this co-regent, ruling as a female queen in the footsteps of Sobkneferu and Hatshepsut. One of the Petrie Museum‘s showcase treasures, the Amarnan Co-regency Stela, appears to prove at least that the co-regency occurred, and that it occurred roughly at the same time as Nefertiti’s disappearance. Showing three figures, largely agreed to be Akhenaten, Nefertiti and Merytaten, Nefertiti’s name is chiselled out and replaced with Neferneferuaten. Could Nefertiti have been the King of Egypt?

A Question of Shawabti

As much as the ‘Pharaoh Nefertiti’ theory is attractive, there are just as many scholars arguing against her kingship. One piece of material evidence used to support opponents is a funerary shawabti, a statuette offered to the gods. Its inscription, below, certainly seems to identify it as belonging to Nefertiti:

As much as the ‘Pharaoh Nefertiti’ theory is attractive, there are just as many scholars arguing against her kingship. One piece of material evidence used to support opponents is a funerary shawabti, a statuette offered to the gods. Its inscription, below, certainly seems to identify it as belonging to Nefertiti:

The Heiress, high and mighty in the palace, one trusted [of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt (Neferkheperure, Wa’enre), the son of Re (Akhenaten), Great in] his Lifetime, the Chief Wife of the King (Neferneferuaten-Nefertiti), Living for Ever and Ever.

Some claim the shawabti was a funerary gift from Nefertiti to her deceased husband. Yet others counter that shawabtis were made in the image of the dead, during the embalming process. Also, the shawabti shows Nefertiti in queen’s attire, not the male co-regent pageantry she would have been wearing had she ruled as king.

Nefertiti is an enigma, and her and her husband’s radical Amarna Period was wiped from records, just twenty years after the new city had been built. Akhenaten would be erased from pharaoh lists by his fundamentalist successors; his beloved city razed and religion laid in tatters. Yet the wonder of his beautiful wife has never relented, the search for her missing body proving one of the enduring mysteries of Ancient Egypt. And never has Nefertiti’s story been thrust into the public eye quite like the story of the ‘Younger Lady’…

Loret’s Leap

Fast forward over three thousand years, and legendary French Egyptologist Victor Loret is scouring the Valley of the Kings in search of the necropolis’ next major tomb. What he eventually excavates at KV35, the tomb of Amenhotep II, is headline-grabbing enough. What he finds stuffed into a secret side chamber is staggering. Twelve mummies had been laid to rest in the tomb, including some of the 18th, 19th and 20th Dynasty’s biggest names: Thutmose IV, Seti II, Merneptah were three major pharaohs. But who should Loret find but Akhenaten’s illustrious father, Amenhotep III! Could this cache contain the remains of the Amarnan royals?

Despite the best efforts of the Cairo Museum, only eight of the twelve ‘secret’ mummies of KV35 have ever been identified. The remaining four comprise an elderly woman, younger woman, unknown woman and a prince, thought by many to be Amenhotep II’s son Webensenu. Some even believe the elderly lady to be Tiye, Amenhotep’s wife. Yet it is the ‘Younger Lady’ which has caught the world’s eye most, for it is she who respected Egyptologist Joann Fletcher claimed was actually Nefertiti during a controversial 2003 expedition. Fletcher pointed to the mummy’s shaven head, which may have been a Nefertiti fashion statement so that she could wear her trademark tall blue crown. Double-pierced earlobes were also rare at the time, leading Fletcher to conclude they may well have been the chosen style of a heretic queen.

Despite the best efforts of the Cairo Museum, only eight of the twelve ‘secret’ mummies of KV35 have ever been identified. The remaining four comprise an elderly woman, younger woman, unknown woman and a prince, thought by many to be Amenhotep II’s son Webensenu. Some even believe the elderly lady to be Tiye, Amenhotep’s wife. Yet it is the ‘Younger Lady’ which has caught the world’s eye most, for it is she who respected Egyptologist Joann Fletcher claimed was actually Nefertiti during a controversial 2003 expedition. Fletcher pointed to the mummy’s shaven head, which may have been a Nefertiti fashion statement so that she could wear her trademark tall blue crown. Double-pierced earlobes were also rare at the time, leading Fletcher to conclude they may well have been the chosen style of a heretic queen.

Discovery Channel’s coverage of Fletcher’s incendiary theory garnered worldwide attention. Yet most Egyptologists point to a lack of DNA evidence, and claim Fletcher was simply trying to make a name for herself. Dr Zahi Hawass, who himself had speculated on Nefertiti having been found in KV35, subsequently banned Fletcher from working in Egypt. Some now even believe Fletcher’s mummy may in fact be that of a young boy. Dr Hawass‘ Nefertiti findings can be found on the National Geographic documentary ‘Nefertiti and the Lost Dynasty.’

Is Nefertiti’s Discovery Waiting in the Wings?

Nefertiti’s missing body still occupies the time of dozens of renowned Egyptologists, none more so than the esteemed Dr Hawass. The Egyptian antiquities chief believes Nefertiti may be inside the ‘soon-to-be-discovered’ KV64, and has vowed to find the famous queen by this winter. Time is pressing – can Egypt’s most famous archaeologist sign off his incredible career at the pinnacle of Ancient Egypt by finding the empire’s most cryptic queen?

Nefertiti may draw more headlines nowadays for the beautiful bust made in her image. But there’s no doubting her status as one of Egypt’s enduring enigmas, and a character who stole the hearts and minds of an entire empire. She may have been famed for her beauty, but there’s much more to Nefertiti than a pretty face.