Egypt hasn’t always been controlled from Cairo – in fact the city only took on its capital city mantle in 969 AD. The ancient Egyptian empire went through over a dozen capital cities in its history, the most notable being Memphis, Thebes, Amarna and Alexandria. But how did power shift between these bustling ancient hubs? And what was life like as a resident of an ancient Egyptian capital?

A Divided Land

Before the empire was united in 3118 BC, it consisted of two separate kingdoms: Upper and Lower Egypt. Upper Egypt consisted of the valley regions of the south, taking in the cities of Abydos, Aswan and Nennusu; later known as Herakleopolis. It followed the Nile between the Eastern and Western deserts, and stopped short of the illustrious trade kingdoms of Nubia and Kush. Lower Egypt, however, comprised the Nile’s northern delta into the Mediterranean Sea; rich in agricultural land and including the cities of Heliopolis, Memphis and Avaris.

Before the empire was united in 3118 BC, it consisted of two separate kingdoms: Upper and Lower Egypt. Upper Egypt consisted of the valley regions of the south, taking in the cities of Abydos, Aswan and Nennusu; later known as Herakleopolis. It followed the Nile between the Eastern and Western deserts, and stopped short of the illustrious trade kingdoms of Nubia and Kush. Lower Egypt, however, comprised the Nile’s northern delta into the Mediterranean Sea; rich in agricultural land and including the cities of Heliopolis, Memphis and Avaris.

Thus for two to three thousand pre-dynastic years until Egypt’s unification, the capitals of Upper and Lower Egypt shifted between no less than eleven cities – Upper capitals comprising Thinis, Nennusu, Khmun, Abydos and Thebes; while Lower Egypt counted Avaris, Tanis, Sais, Bubastis, Heliopolis and Memphis among its premier locations. However, when the legendary king Meni (Menes in Greek), who has also been identified as the historical king Narmer, brought the two entities together in 3118 BC he made Memphis his capital. And Memphis would maintain its premiership for almost 1,200 years.

Memphis

Ineb Hedj – meaning the ‘White Walls’, was a strategically placed city just south of today’s Cairo at the foot of the Nile delta. As such it could be used to watch over matters in both former nations, leading to its Middle Kingdom name of Ankh-Tawy – ‘That Which Binds the Two Lands’. Through the ancient accounts of the likes of Herodotus, Memphis can be seen as an incredibly cosmopolitan city – and two thousand years later, by the time the Persians conquered Egypt, Herodotus counted Greeks, Jews, Phoenicians and Libyans among Memphis’ thousands. In fact according to Chandler & Fox, Memphis was the most populated city in the world almost continuously until around 700 BC.

Sadly, little actually exists of ancient Memphis today. Its size can best be calculated by taking a look at its necropolises, in particular the archaeological playground of Saqqara. Not only does the sheer number of burials show the unusually large number of people who died in Memphis, but a glut of impressive royal monuments – such as Djoser’s step pyramid (the first such in Egypt) – shows how early Egyptian monarchs wanted to cement their posterity in Memphis, which would have rocketed the city’s stature during the empire’s infancy.

Memphis also held great importance throughout the empire for its status as a flagship of religious belief. Most scholars now insist that Ptah, the subject of a temple in the city, was Memphis’ main deity. Later, in the 14th century BC, the city became the focus of one of the empire’s greatest religious scandals when Tutankhamun moved to officially reject the heretical cult of Akhenaten in Memphis.

Yet Memphis could not hold onto its regency, and succumbed to Thebes as the capital when the Theban king Nebhepetre Mentuhotep won a civil war in around 1650 BC and instated his home city as capital. However, following the tumultuous Amarna Period, the capital was restored to Memphis in 1319 BC for a short while before Ramesses the Great began his successful tyranny by moving the capital north to Pi-Ramesse in the delta. However Memphis’ power and population were unerring, and it took Greek intervention in 331 BC, when they moved Egypt’s capital once more to Alexandria, to hinder the city’s dominance.

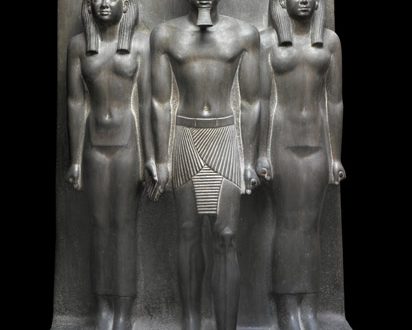

The demise of Egyptian polytheism and the rise of Greek mythology, the Copts and Christianity meant Memphis’ power waned. When Muslims arrived in 641 AD, they established their capital ostensibly in Memphis, but actually a few miles north (now a Cairo suburb) effectively marking the end of Memphis’ status as a world power. Now all that stands of ancient Memphis is the ruins of Mit Rubina, as well as a fraction of the great temple to Ptah and some famous statues, such as those of Ramesses the Great; and the Alabaster Sphinx.

Thebes

Thebes, already an important city in Upper Egypt, became the empire’s capital in 2040 BC when the Theban kings emerged victorious from their civil war, founding the Middle Kingdom. It had previously been known as Waset, the eponymous capital of the fourth Nome of Upper Egypt – and even during its tenancy as capital it lived largely in Memphis’ shadows. Yet Thebes more than holds its own in terms of important sociological and religious Egyptian sites; including the famous temples at Karnak and Luxor. In fact Thebes’ heritage has lived on in the form of the modern city of Luxor, home to almost 400,000 people.

When the Theban kings took control of Egypt, the city began to acquire some of its most eminent structures. Nebhetepre instantly built the temple at Deir el-Bahri; added to famously by Hatshepsut during her sovereignty of the 18th Dynasty. However, as the Thebans’ sphere of influence drew colder, Thebes’ political clout took a beating, and it had to settle for the title of religious centre until its revival in the 18th Dynasty. Indeed, as was previously mentioned, Thebes, struggled to hold onto that title thanks to the centuries of religious history preceding Memphis. However Thebans could revel in the fact that, in 1500 BC the High Priest of Amen in Thebes became more important than the High Priest of Ptah in Memphis. And Thutmose I would soon become the first pharaoh interred at the now-famous Valley of the Kings, located just outside Thebes.

In fact it was religion which would carry Thebes into its second golden era, in the years following Ramesses III’s building of the Temple at Medinet Habu in 1194 BC. Then the High Priests of Amen usurped the Egyptian throne, reinstating Thebes as the capital of a now-divided empire in 1069 BC. However when the priests were defeated and the Nubian Dynasty seized Egypt, Thebes’ influence waned and it would never see the title of capital again.

Yet what remains of the city, compared with its unspoken rival Memphis, is startling. For one there are the satellite necropolises and temples of Deir el-Bahri, Karnak and Luxor, which hold great sway in the history of Egypt. And the Valley of the Kings has been world-famous ever since the age of discovery, during and beyond the 19th century. Even Greco-Roman temples, worshipping the crossover gods Hathor, Thoth and Isis, remain. Even Amenhotep III’s Colossi of Memnon stand tall over Thebes, guarding his mortuary temple from would-be attackers. So Thebes may not have held the same population or political clout as Memphis during its time as capital, but it is one of the most treasure-laden cities in the whole country.

Amarna

It may not have enjoyed the longevity, ancient posterity or monumental significance of Memphis or Thebes, but Amarna deserves a special mention as one of ancient Egypt’s great capital cities for its part in one of the empire’s most notorious and legendary phases.

It may not have enjoyed the longevity, ancient posterity or monumental significance of Memphis or Thebes, but Amarna deserves a special mention as one of ancient Egypt’s great capital cities for its part in one of the empire’s most notorious and legendary phases.

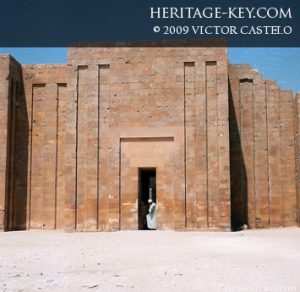

Sitting 365 miles south of Cairo, 250 miles north of Thebes and on the site of the modern town of al-Minya, Amarna may not have seemed the most auspicious of locations for a capital city. It sat between two rows of cliffs, in a quasi-valley lasting 12km, creating a natural amphitheatre of sorts. And when the 18th Dynasty pharaoh Amenhotep IV, son of Amenhotep III and his chief wife Tiya, rose to the throne in 1532 BC, it was to become the theatre in which an epic religious and political saga would be played out.

Around three years into Amenhotep IV’s reign – by which time he had renamed himself Akhenaten (meaning ‘Horizon of Aten’) – he built a huge temple to the relatively new sun god Aten at Karnak. It would be a precursor of the drama to follow: just two years later, Akhenaten would move the capital from Thebes to the virgin site of Amarna, to build a new city in the glory of the cult of Aten, much to the disgust of much of the empire. Some Egyptologists have called the cult Egypt’s first monotheism; yet it was more a henotheism, in which Aten was raised in stature above all other gods.

Amarna’s early days saw a monumental rise in population as people flocked to the home of their king. Some estimate the city’s population to have been as much as fifty thousand, bringing it immediately in line with the other main cities, such as the two huge former capital cities. Hundreds of normal houses have been excavated, as have utilities such as grain houses and harbours. Yet it is the city’s nucleus which contains its two most infamous and decorative structures. The Royal Palace is a grand structure from where Akhenaten and his famously beautiful wife Nefertiti lived. And the Great Temple was the focus of the king’s heretical cult which would tear the empire apart.

It must be noted that Akhenaten and the Amarna Period led to some of the most ornate and enlightened artwork in the empire’s history, and much of the archaeological material gathered from Amarna shows signs of incredible skill and diligence. There has even been much theorising that depictions of the royal couple at the time represent the earliest guise of surrealism. Yet the effective demise of traditional gods under Aten, under which anything which did not serve him was deemed unholy, was far too much for most Egyptians, and the Priests of Amun, to take. However, Akhenaten died of natural causes and it was only after his death that future kings – led by Akhenaten’s advisor Horemheb – destroyed Amarna and reinstated the traditional Egyptian beliefs. Thus in 1319 BC, only around twenty years after its inception, Amarna was deserted and would be confined as a blip in the empire’s history.

There are many other major cities and de facto capitals, used for political or military purposes for a short time, which rose to prominence during the ancient Egyptian empire. Yet it is surely Memphis, Thebes and Amarna which capture the essence and beliefs of their time, right up until the Greeks made Alexandria the capital of a broken Egypt.