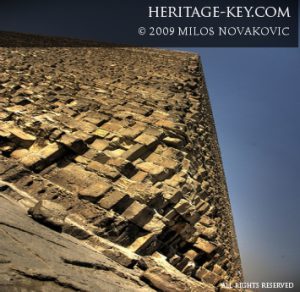

The s of the ancient Egyptian pharaohs have long stood proud as some of the world’s greatest architectural achievements. The heralded leaders to whom they were devoted are known throughout the world, yet the stories of the men who built them have remained hidden until recent times. Who were these people, how did they construct these massive mausoleums – and why did they devote their lives to such a breathtaking task? Modern archaeology and ancient testament may hold the key to these questions.

Who Were They?

Age-old storytelling, myth and the mysticism of the structures themselves, has led many in the past to question whether the s’ labourers were Egyptian – or, if you can believe some of the more outlandish suggestions, human at all. Technicolour tales of Jews being brutally whipped into action by pharaonic slave drivers has warped the public’s perception of the s’ construction, and even of the Egyptian civilization as a whole. Yet the truth is much more urbane, with scores of devoted Egyptian labourers moving to the site of the on a seasonal basis; most returning to their families and careers after a certain number of months – much like life on a modern construction site.

However there were also many builders who stayed at the site for years on end, and appeared to gather together with a great spirit – embodied in the creation of their various gangs; the inscriptions of which are littered across the stones of Egypt’s great monuments. For the construction of the Great of Khufu at Giza, for example, most Egyptologists arrive at an estimation of around 20,000 casual workers per 5,000 permanent labourers. Some have argued these workers were effectively conscripts; bound by the royal law which decreed the Pharaoh could compel anyone to work on a state project on a three to four month basis. However pre-eminent Egyptologists Mark Lehner and Zahi Hawass have suggested that labour was voluntary. Hawass points to the awe-inspiring socialising power of the s, while Lehner likens their construction to that of an American Amish barn-raising, whereby everyone adds their hand to the cause.

Living in the Shadows

So where did the scores of tired workers slope back to after a hard day’s graft? Little was known of the domestic lives of the builders – and indeed very few cared, with all the glittering monuments rising from the sand in the early years of modern archaeology. Yet in 1888 the heralded British archaeologist Flinders Petrie uncovered an entire town beside the Middle Kingdom necropolis of Senwosret II at Illahun; Kahun.

So where did the scores of tired workers slope back to after a hard day’s graft? Little was known of the domestic lives of the builders – and indeed very few cared, with all the glittering monuments rising from the sand in the early years of modern archaeology. Yet in 1888 the heralded British archaeologist Flinders Petrie uncovered an entire town beside the Middle Kingdom necropolis of Senwosret II at Illahun; Kahun.

Here Petrie discovered mud brick houses, papyri, pottery, clothing and even children’s toys – the building blocks of the domestic lives of the builders. These terraced settlements have since been echoed in finds spanning the country, including that of the Giza necropolis – which includes the ‘Wall of the Crow’; a huge limestone boundary marking the divide between the land of the living and the land of the dead. Unfortunately, this rampart and much of its harbouring village now lies beneath the modern town of Nazlet es-Samman, rendering it inaccessible. However, what archaeologists have unearthed is a series of desert cemeteries on a nearby sloping hill, which have been left alone by the infamous grave robbers who plundered many of the Egyptian royal tombs.

Smaller fragments of the s, probably waste material, are a regular feature of the cemeteries – showing the importance everyday ancient Egyptian placed on the afterlife. The number of women and children found in the 600-strong resting place also confirms the theory that builders lived in the shadows of the s with their families. But as well as this devotion to the dead, the workers built an entire community around their lives working onsite. Lehner has uncovered a copper processing plant, a fishery and even two large bakeries near Nazlet es-Samman. Animals were shipped from all over the country for slaughter at the site, as the myriad bones remain testament to. Some houses – presumably those of the higher-status permanent workers – even had drainage systems. This was not so much a camp as a fully-functioning workers’ city. Indeed, compare the living conditions, camaraderie and working hours (most experts suggest around a ten-hour working day) of the builders with those of modern migrant workers in, say, Dubai – who are forced to work up to twelve hours a day for little pay, highly dangerous work and poor living conditions – and you’d be forgiven for thinking humanity hasn’t actually come that far in over 4,000 years.

A Daunting Task

They may have lived relatively modern and comfortable lives outside work – but the tools builders used for the tasks at hand were anything but. To a lay man today the s evoke a sense of spectacular modernism and engineering prowess – yet they were devised with the simplest of aids. Threads were used to make straight lines; angles and measuring arms to calculate inclines and the like; and straight edges for, well, straight edges. The huge stone blocks, hauled into place on sleds (wheels would have sunk into the soft ground) by beasts of burden, were chipped and perfected with nothing more than simple copper or bronze implements such as chisels and picks. Bearing in mind that many of these massive blocks are so tightly packed one cannot slide a knife between them; it is nothing short of spectacular such intricate measurements were carried out in such primitive times. Even the vast granite blocks, gathered from sites such as Aswan, were quarried with nothing more than large stones and brute force.

Thank Gods

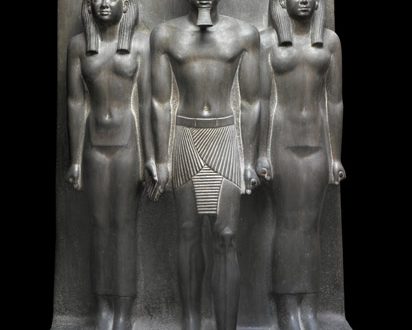

With all this devastatingly hard work in mind to build monuments to the afterlife, it’s no wonder that construction of the s and religion were so inextricably linked. In fact, a building itself, built with solid materials, assumed the power of giving life in this world through the magic of simulation, whilst allowing immortality in the afterlife – even if no religious ceremonies were held there. Tombs were commonly shaped like houses because Egyptians believed a tomb was a microcosm of the afterlife, including all its accoutrements – such as sacrificed animals, and rocks carved from holy places. Indeed the funerary inscriptions found in nearly all ancient Egyptian tombs were not merely decoration; they were offerings, praises and requests to the gods. The s were not just a chance to anthropomorphise the Egyptian monarchs, but also a way of communicating with the afterlife.

An Enlightened Time

Modern scholars may see architectural and building techniques as advanced, their purpose grandiose and their devotees socialised in a collectively constructive way rarely seen in subsequent civilization – but it was the everyday lives of these incredible men and their families which really brings home the modernism of the ancient Egyptians. Compared to many working conditions today, they were better looked-after, had efficient living quarters and worked in troupes dedicated solely to the adoration of their rulers. Modern construction may have plenty to learn from these pioneers.