This year’s Egyptological Colloquium, held in the British Museum‘s fantastic BP Lecture Theatre, was roundly applauded as a great success. No fewer than eighteen gifted minds took to the lectern, as a glut of opinions, theories, excavations and discoveries were explored to a large audience’s enthralment. Some of the speeches were incredibly specialist; others not so. But what is certain is that the past week has seen some of the most compelling and intriguing axioms on one of Ancient Egypt’s greatest pieces of iconography, the Book of the Dead. From colours to kingdoms, magic bricks to evil demons; the colloquium had it all in abundance. And Heritage Key is on hand to give you all the best of the event’s ideas from the bleeding edge of Egyptology.

Colourful Conclusions

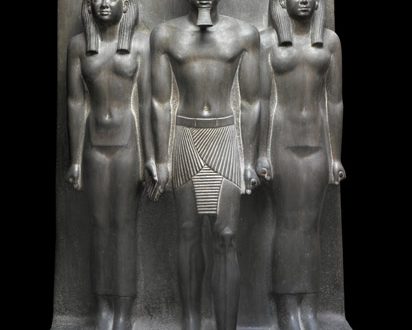

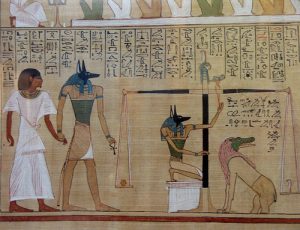

To all those non-Egyptologists – and I’m guessing this numbers most – the most immediately striking features of the Book of the Dead, in all its forms, are the vividly-coloured gods, demons and mortals playing out hundreds of ceremonies making up the entry to the afterlife and beyond. So it was Rita Lucarelli’s work on the Guardian Demons of the book which would have caught the eye more than most. Demons have been prevalent in ancient and modern religions, from Assyria to Japan. But the Book of the Dead’s myriad demons have long been viewed with a certain level of curiosity, thanks to their iconographic ambiguity. Dr Lucarelli proceeded to debunk some of the myths surrounding them, using specific chapters (144-147) and some stunning photography. Two types of demons prevail in the Book; ‘wanderers’ and ‘guardians’. Wanderers carry out punitive functions and drift from the world to the netherworld, while guardians are bound to their world, compelled to guard the doors to the afterlife. For an uninitiated fan, I was most impressed with the vast array of colourful guises demons took, and how they are easily confused with gods: Rabbits, hippos, cows and falcons are all prevalent. Demons also make use of weapons like knives and bows and arrows, in their quest to rid both worlds of impurity, in a sort of Ancient Egyptian purgatory.

Another speech which made great use of imagery and colour was Holger Kockelmann‘s work on the use of light, particularly the Sun Disk, in New Kingdom and Ptolemaic Books of the Dead. Spell 154 was examined in detail, as was the various pictorial depictions of light entering the body of the deceased. It was fascinating to see how even the tiniest changes in iconography could show how certain eras saw light and the qualities it possessed. Solar rays could be shown as tears, raindrops or even ankh signs; each one nourishing its target and preparing them for the afterlife. Dr Kockelmann also touched on the intrigue of the Temple of Dendera where, in lieu of sun disk imagery, a shaft of light physically rained down upon the mummy, as a mummified Osiris watched on from the shaft itself. Dr Kockelmann’s paper comprised a great deal of colour-specific material, but it was the British Museum’s own Richard Parkinson and Bridget Leach who provided some of the event’s most fascinating chromatic sagacity, with their talks on the provenance of dyes and paints which went into creating the brilliant technicolour of the Book of the Dead’s borders and vignettes. Whole slave mines were used to excavate some of the more sought-after hues, and the fading of these over time has meant we can now see in more detail the process of putting together each stunning .

Local Traditions

The strong local traditions which typify editions of the text and vignettes played an integral role in the colloquium’s lectures; specifically the differences between those of Theban and Memphite origin. The University of Bonn’s Marcus Muller, one of Egyptology’s rising stars, outlined many of the opposing features in one of his two imposing lectures at the event. Looking in particular at the Book of the Dead in the Late Period, Dr Muller showed that, though Karl Richard Lepsius‘ 1842 publishing of papyrus Turin 1791 is considered the standard for Late Period reference, only a small percentage of the 1,400 known papyri of the era with vignettes have ever been published. Thus, and by using several anomalous papyri, Dr Muller showed that Turin 1791 should not be made such a central work. The Theban tradition was revisited by Malcolm Mosher Jr, who in a succinct and poignantly illustrated lecture outlined no fewer than seven primary sources from across the world which appear to display their own idiosyncratic style, in the way they are ordered, through stylistic features such as the number of snakes appearing in headgear, and that the very text in the spells evolved according to the tradition. Dr Mosher concluded that this ‘style’ can be useful in dating other Theban Books of the Dead, something which frequently eludes modern historians. It also runs concurrently with Dr Muller’s assertions that the current pigeon-holing of Books of the Dead is far too broad and misses much of the nuance which makes it such a compelling artefact throughout its history. A similar notion was tabled by Oxford University’s Burkhard Backes, who outlined three more anomalous texts from Late Period Thebes. Dr Backes’ work nodded more towards the cultural context of the three papyri; adding more weight to the idea of specific workshops creating their own copies. The texts’ incomprehensibility links them inextricably, and each one has its own unique sequence of spells. Thus their scribes must have had enough information on the Book’s cultural significance to make a deliberate choice.

University of Bonn professor Dr Irmtraut Munro revisited the Theban tradition for her talk, yet put forward a convincing argument that at least two 26th Dynasty Theban papyri show Memphite characteristics which suggest a master copy. This idea was featured in detail by Cairo University’s Tarek Tawfik, who looked specifically at the vignette of the first chapter of the Book. Dr Tawfik gave evidence to show that tomb inscriptions and funerary scenes from the Ramesside Period onwards are in fact simply copies of the early first chapter scenes. Isabelle Regen presented a valuable insight into the magic bricks which were outlined in the Book of the Dead. By taking a colourful look at renowned examples, such as those found in the tomb of Tutankhamun, Dr Regen showed that there are many discrepancies between what is ordered in the Book and what is put in the tomb. Again, as very much an outsider the argument, backed by some startling visual backing, was one of the most entertaining of the two days, helped by its evocative subject matter.

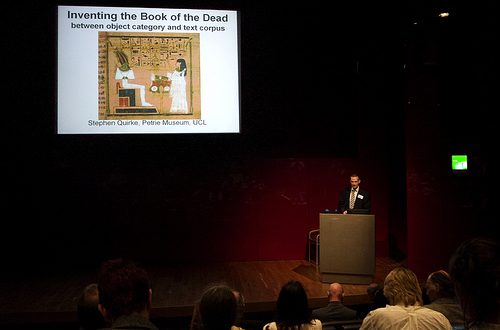

More speeches looked at trends in specific chapters, and how they were presented in various forms. The University of Geneva’s Annik Wuthrich presented a fascinating lecture on the Osirianisation of Amun-Ra in the 21st Dynasty, through chapters 162 and 166. The two problematic chapters give prominence to an unnamed god, but Dr Wuttrich showed effectively that, by studying theological trends in the era, this mysterious character can actually be equated with Amun-Ra, who by then was becoming more and more synonymous with Osiris. The Petrie Museum‘s Stephen Quirke gave one of the event’s more unique slants on the Book, by attempting to debunk some of the apparent mistakes and anachronistic studies on the Book in its early years in the Egyptological zeitgeist. Showing that early scholars were too focused on finding a master copy for the text, Dr Quirke showed how the invention of the Book of the Dead was a) an introduction of a new ritual in new content, and b) through the introduction of new forms as dominant over others; for example the use of book-rolls instead of painted wooden coffins in the 18th Dynasty.

Into the Future

But the colloquium wasn’t just focused on the past. Several exciting new projects were commented on, which keeps the studying of the Book of the Dead in rude health. Maarten Raven showed how the University of Leiden’s ongoing excavations at Saqqara, the ‘City of the Dead’ are changing how some vignettes of the Book, such as Ch110, which appears to refute Abdul-Qader Muhammed’s 1966 claim that the spell only occurs in Ramesside tombs. In his second talk, Dr Muller kept the audience updated on the excellent Book of the Dead – Totenbuch – project. The 15-year-long project has already spawned many publications, and two more have recently become available – showing that the mission is still going strong. And whilst the University of the Sarbonne’s Chloe Ragazzoli outlined traces of workshop production in the Book of the Dead of Ankhesnet showed how the French National Library (BNF) is undertaking a new project to make available many more of the wealth of unpublished papyri in the country.

The last but by no means least word was left to Brigham Young University’s John Gee, who presented an emotive argument examining the Book of the Dead as canon. Dr Gee asked the question of whether Egyptians had a standard orthodox liturgy like the Christian Bible. Over a number of criteria, including ‘Standardisation’, ‘Quotation’, ‘Commentary’ and ‘Archaeological Placement’, Dr Gee managed to put forward a convincing claim that his supposition could at least be possible – though many of the audience will have no doubt baulked at a comparison between the two scriptures. It was astounding that no-one stood up in opposition, yet to be fair it was getting rather late, and everyone was understandably lacking in energy following two days of intense Egyptological study. Still, no-one could suggest the colloquium had not been a great success, and it showed that the study of the Book of the Dead is enjoying something of a modern renaissance. And thanks to the youthful exuberance of many of the event’s speakers, the future for its enlightenment looks as bright as ever.