From Sheep Pasture to Number One Tourist Attraction

From Sheep Pasture to Number One Tourist Attraction

The Roman Forum and the surrounding monuments, such as the Colosseum and the Imperial Forum, are today considered to be some of Rome‘s most valuable heritage sites. They are visited by millions of tourists each year and generate vast sums of money towards their own maintenance, not to mention the associated income from the tourist industry. Efforts are made to protect and preserve them. But it hasn’t always been that way.

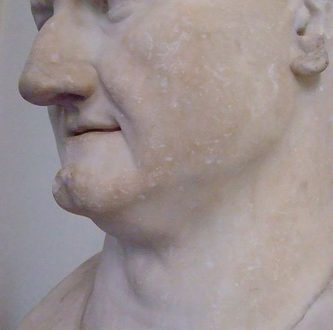

During the 18th century when Grand Tourists – usually rich, young men on a gap-year-of-yore – came to Rome, the Roman Forum would have looked very different. For a start, it wasn’t barricaded off from the public, and the monuments were not so perfectly restored. Picture Piranesi’s etchings of people collecting water from the fountain that used to stand in the forum, now in piazza del Quirinale, farmers taking animals to pasture there and the temple of Castor and Pollux with shrubs growing on top, and you’ll the idea.

Paving Over History

Perhaps the biggest difference of all was that there was no four-lane, heavily trafficked road straight through the forum area, dividing the Roman Forum from the other Imperial Fora (the fora of Trajan, Augustus, Caesar, Nerva and Vespasian).

This road – via dei Fori Imperiali – was built between 1931-1933 at the behest of Benito Mussolini, leader of Italy’s National Fascist Party. Primarily he wanted a road fit for a triumphal march or parade. He also wanted to create a physical and symbolic link between the Fascist party’s headquarters in piazza Venezia and the seat of ancient Roman power in the forum, all the way to the Colosseum. Some obstacles lay in the way of the road though – not least the millennia-old Roman structures, as well as the popular tenements that housed 746 of Rome’s poorest families. The latter had little political clout or voice to fight the plans to rehouse them and the Alessandrino neighbourhood – one of the most densely populated and oldest inhabited areas of central Rome – was systematically pulled down.

Apart from the human impact of displacing thousands of people (many of whom were rehoused in periphal estates in Rome, such as Primavalle – an area still blighted with social problems), there were many other structures that were destroyed, moved or covered over during the building of the road. According to the book Via dell’ Impero, Nascita di una Strada, which accompanied an exhibition of the same name, these include:

- The de-consecration and stripping of the Church of Sant’Adriano in the Roman Forum.

- Demolition of the 17th century convent of the Mercedari, annexed to the Church of Sant’Adriano.

- Excavation and removal of a large part of the Velia Hill, on which the Basilica of Constantine stands (also known as the Basilica of Massenzio), half way between the Colosseum and piazza Venezia.

- Destruction of the monastery of Sant’Urbano ai Pantani and the nearby convent of Sant’Eufemia.

- Destruction of the Alessandrino neighbourhood, which included the house of famous 19th antiquarian Francesco Martinetti, collector, restorer and numismatics expert – itself a treasure trove.

- Excavation and covering of the gardens of the 16th century Villa Rivaldi and its nymphaeums.

- Loss of several notable houses including Casa Desideri, Casa Ciacci, Casa Cetorelli and Casa De Rossi.

- Demolition of the churches of San Lorenzo ai Monti and Santa Maria degli Angeli in Macello Martyrum.

- The excavation and partial obliteration of the forums of Caesar, Augustus, Trajan, Vespasian and Nerva.

Of the areas excavated, a great deal of data has been lost. A recent exhibition about the building of the road (reviewed here) at Musei Capitolini noted that many of the objects found were stored in crates in the vaults of Museo della Civiltà Romana, but little associated data was recorded about the exact location and context of the objects, meaning that huge amounts of information that could be inferred is now irrecoverable.

Whatever benefits may have been gained from the rudimentary archaeological processes that were given an impetus by Mussolini’s road-building plan, the via del Fori Imperiali completely changed the landscape and character of the heart of Rome and sliced the forum area in two. General outrage is often the reaction of modern archaeologists and scholars when discussing it. David Watkin, professor of the history of architecture at Cambridge University, is in no doubt that the road should – and will – be removed.

He notes in his book, The Roman Forum, that the name via dei Fori Imperiali “is ironic, since it obliterated over 84 per cent of the recently excavated forums of Nerva and Trajan.” He also adds that “40,000 square metres of one of the most historic parts of medieval and Renaissance Rome was destroyed, including five churches and many houses, of which it is now difficult even to find photographs.”

Opening up Spaces

The road formed part of Mussolini’s vision of a ‘new’ Rome. He declared in 1925 that his aim was to “liberate the trunk of the great oak from everything which still smothers it. Open up spaces… Everything that has grown up in the centuries of decadence must be swept away.”

And open spaces is exactly what he achieved. Quite apart from the ‘space’ obtained by the new road, demolition workers also succeeded in freeing up some space taken up by the ‘smothering’ baroque and Renaissance buildings that surrounded the Capitoline Hill, the Pantheon and the Theatre of Marcellus.

Via della Conciliazione is another example of a residential area being torn down to make way for a grandiose road fit for a triumphal parade. This time the monument being ‘liberated’ was St Peter’s Basilica and a vista was opened up between the basilica and the Tiber. Again, a large section of tenement buildings had to come down and residents were rehoused – amid protests – in the newly built estates outside Rome. Work began in 1936 but Mussolini didn’t live to see its completion.

Mussolini the Self-styled Emperor

Mussolini’s drive to ‘prune back’ some of the ‘unessential’ historical landmarks and buildings of Rome was a curious contrast to his own personal and his party’s identification with the ancient Romans. He certainly admired them and sourced much of his vision of leadership from them – but at the same time he aspired arrogantly to build bigger, better buildings than the Romans – in an attempt to make Rome grander than it had ever been before. To understand the Fascist attitude towards Roman archaeological heritage, we need to also consider the Fascists’ self-aggrandising identification with the Roman empire, their aspirations to follow the imperial model of colonisation and perhaps most of all, the personality cult of Mussolini.

His official self-given title, which included the appellation Founder of the Empire, provides a clue as to the intentions of Il Duce. He modelled himself on Julius Caesar, who was named ‘dictator in perpetuity’ in around 49 BC, and some of Mussolini’s populist campaigns echoed those of Caesar. Rome’s first emperor, Augustus, was also a role model and Mussolini promoted the idea of a second ‘pax Romana’, promising peace after the First World War. He also sought to expand Italy’s colonial empire by invading Ethiopia in 1936 and by occupying Albania (aggressions that are in the context of European colonisation of much of Africa in the 19th century, and particularly Italy’s invasion of Libya, part of Egypt and Somalia in the decades before the Fascist movement evolved).

Mussolini tried to consolidate his identification with the first Roman emperor when, in 1937, he opened an exhibition celebrating 2,000 years of the birth of Augustus, Mostra Augustea della Romanità. The main point of the exhibition was the section describing the links between Fascism and ancient Rome. Apparently Il Duce was presented with a live eagle during the exhibition’s closing ceremony.

The New Augustus?

Since Mussolini particularly wanted to associate himself with Augustus, in the 1930s his attentions turned to two valuable Roman monuments: the Ara Pacis and the Mausoleum of Augustus. The latter was once the burial site of dozens of emperors, including Augustus, Tiberius, Caligula, Nero and Nerva – not to mention famous Roman women including Livia, Agrippina the Elder and Poppaea Sabina. It was one of the most impressive mausoleums ever built, covering two hectares of land and clad in white marble. Mussolini’s head press officer, Gaetano Polverelli, suggested converting the Mausoleum of Augustus into a temple to Fascism. To be fair, any crude restoration of the tomb by the Fascist state was unlikely to damage it much further than it already had been during the ages. Having been sacked in 410 by the Goths, fortified in the Middle Ages by the Colonna family before being abandoned, then used as an area for bull fighting and concerts in the 19th century, the site was in ruins anyway – and it still is today. It is not open to the public.

As for the Ara Pacis, built in 13 BC as Augustus’s dedication to peace, sculpted panels from it had been found buried in the Campus Martius in the 16th century – but nobody had realised that these panels were part of one of the most valuable altars built in Roman times. The monument had been buried by centuries of detritus and its various panels and components had fallen apart underground. In the 19th century, more white marble panels were found on via in Lucina (off via del Corso, Rome’s main shopping street) and experts began to hypothesise that these might belong to Augustus’s Altar to Peace. In 1937, experts were able to extract the remaining parts of the altar from the ground. They get full marks for putting in place this delicate archaeological project in the first place (the altar had formed part the foundations – then water-logged – of an existing building, so that the ground had to be first of all frozen before the marble panels were removed and concrete piped into the ground to take their place). However, what the Fascists did next sparked considerable controversy and is part of a debate that continues to this day.

The Ara Pacis was reconstructed and given a new home on the banks of the Tiber. But this was problematic, and again tenements that had stood there for hundreds of years were torn down to create the modern Piazzale Augusto Imperatore as a setting for both the Ara Pacis and the Mausoleum of Augustus. A pavilion by Morpurgo was built to house the altar – but this was not satisfactory and American architect Richard Meier designed a new structure for the piazza, opened in 2006 – criticised by many for not blending with Rome’s classical architecture and turning its back on the churches and other centuries-old buildings surrounding the piazza. While Meier’s design is the subject of ongoing heated debates, the Mausoleum of Augustus is closed to the public and in bad condition. It seems that neither of these two restoration projects, initiated under Fascism, has stood the test of time – in fact both resulted in irrevocable damage to Roman heritage.

Fascists and Roman Ideology

In his book Fascist Italy, the author John Whittam writes: “Fascist propaganda and rhetoric cannot be fully understood without reference to the regime’s growing obsession with ancient Rome.” Although civilisations and movements had before identified closely with the Roman empire (think of The Holy Roman Empire in Germany from the 10th to the 19th centuries) the Italian Fascists seemed to feel a particularly close bond with their imperial predecessors.

The peninsular now known as Italy was unified in 1861 – the last time the peninsular had been ruled by one power was before the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the fifth century. Rome became the capital of unified Italy in 1870 and this is when the myth of ancient Rome perhaps came alive again. According to Whittam, ancient Rome was taught alongside Italian history as part of the school curriculum – more so during the Fascist inter-war years.

Even the name ‘Fascist’ refers back to the ancient Roman custom of carrying the ‘fasces’, a bundle of white birch rods, tied together with a red strip of leather or material, sometimes with an axe included in the bundle. The Roman fasces represented power through unity – an ideal that the Italian Fascists aspired to. Other Roman symbols of power, such as the wolf and the eagle were also displayed during Fascist marches.

Academics during the 1920s and 30s were encouraged to foster and develop the idea that the Italian Fascist movement was a legacy of ancient Rome, according to Jonathan Perry in his book The Roman Collegia: The Modern Evolution of an Ancient Concept. However, this view also became dangerously associated with race and ethnicity. The Institute of Roman Studies was formed in 1925 by Carlo Paluzzi and it was entrusted with the task of formulating a ‘coherent fascist classicism’, arguing that Fascism was the ‘rebirth’ of the ancient civilization and spreading the ideology through university lectures and scholarly magazines such as ‘Roma’.

This latching on to the legacy and ethos of ancient civilizations reverberates throughout the extreme right. The German Nazis had an obsession with Egyptology based on their association of ‘Pharoah as Fuhrer’, and attempted to twist the county’s history to suit their ideologies. Iraq’s Saddam Hussein went a step further by suggesting that he was some kind of incarnate of the ancient Babylonian tyrant Nebuchednezzar II. Ironically, after rebuilding (without much accuracy) the monuments of his predecessor, one of them – the Ziggurat of Ur – is now used as a US army base. Both Hussein and the troops have caused appalling damage to the site.

Rebuilding Rome – as it had Never Been Before

The Fascists were intent on putting their own marks on the capital and wanted to leave huge monumental buildings to equal those that had already existed in the city’s centre for more than 1,600 years. The architecture was on the scale of the grandest of antiquity’s temples, and followed the classical traditions of columns, arches, grand stairways – but all with a modernist interpretation.

Two years before the beginning of the Second World War, construction started three miles south of the Aurelian walls. This was an area that Mussolini wanted to dedicate to the World Exhibition – which ended up being cancelled anyway, eclipsed by war. The area was known as Esposizione Universale Roma, or EUR, and is typified by large open spaces and large buildings with imposing entrances that dwarf the people who use them. The person mandated to oversee the design of Rome’s new quarter was Marcello Piacentini, Mussolini’s favourite architect.

Some of the main buildings at EUR are:

-

Palazzo della Civiltà del Lavoro, also known as the ‘Square Colosseum’ or the ‘Swiss Cheese’. Photo by bass_nroll on Creative Commons.

Palazzo della Civiltà del Lavoro, built between 1938-43, which many people refer to as the ‘square Colosseum’ due to its six layers of arches. It’s an imposing building that can be seen for miles around.

- Palazzo degli Uffici dell’Ente Autonomo, a heavily colonnaded building that echoes the Roman (and Greek) temples such as the Maison Carrée in Nîmes (itself based on the destroyed Temple of Apollo in Rome). This building is replete with mosaics and reliefs in the Roman style, some echoing the scenes of the sack of the temple at Jerusalem on Trajan’s Arch – a chilling reference in its Fascist context when it was built between 1937 and 1939.

- EUR even has its own Egyptian obelisk – a reference to the Roman emperors’ love of Egyptian styles. This stela was dedicated to Giuseppe Marconi but lacks the elegance of the original obelisks in Rome (there are eight Egyptian obelisks in Rome, and five ancient Roman obelisks).

- Palazzo dell’INPS is fronted by a curved arc of columns, clearly inspired by Trajan’s markets in Trajan’s Forum.

- Where Augustus, Trajan and Nerva had gone before him, Mussolini decided to follow. He even had his own forum built – initially known as Foro Mussolini, it is now called Foro Italico. It is a sports complex including the Stadio Olimpico, the Stadio dei Marmi (replete with classical-style marble statues) and a swimming pool complex (where the World Swimming Championships 09 were recently held).

Today the buildings at EUR house public ministries, offices and museums. The area is often deserted, visited by very few tourists, and the larger-than-life white marble buildings often stand silently in empty squares. They are a lasting reminder of how the Fascists wanted to shape their city and their aspiration to be bigger and more powerful than the Romans. If only Mussolini had begun by building EUR in 1931 instead of devoting his attention to building via dei Fori Imperiali straight through the heart of Rome and the ancient Roman Forum.

Photos by: riccardodivirgilio; Museo di Roma-Archivio Fotografico Comunale; Filippo Reale; socorro66; bass_nroll.