Abydos is arguably the most sacred site of ancient Egypt, and quite possibly the most important archaeological site to Egyptology. Many would argue that other locations, such as the Memphis Necropolis or the Valley of the Kings are much more important, but before you cringe at the above statement, consider the work of the Pennsylvania University, Yale University, and New York University Institute of Fine Arts’ joint expedition to Abydos. After more than four decades in the field, the Penn-Yale-IFA expedition held a symposium at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology on September 19, 2009.

Abydos is arguably the most sacred site of ancient Egypt, and quite possibly the most important archaeological site to Egyptology. Many would argue that other locations, such as the Memphis Necropolis or the Valley of the Kings are much more important, but before you cringe at the above statement, consider the work of the Pennsylvania University, Yale University, and New York University Institute of Fine Arts’ joint expedition to Abydos. After more than four decades in the field, the Penn-Yale-IFA expedition held a symposium at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology on September 19, 2009.

The cemeteries of Abydos have long been understood to be the oldest royal burial grounds in Egypt, dating back to the predynastic chieftains and kings of the Naqada Periods. It is also known that the Temple of Osiris at Abydos was the site of annual pilgrimages attended by thousands, including the Pharaoh, where an annual procession from the Resurrected God’s symbolic tomb in the Umm el-Qa’ab graveyard to the temple itself marked the continuity of the kings, the people, and the land itself. Egyptologists know that even after royal (and common) burials were located elsewhere, symbolic tombs (cenotaphs) were built at Abydos to secure the link between the departed and the Living God.

What is not so widely known is that Khasekhemwy, the last pharaoh of the Second Dynasty, may have constructed a cult complex that was the blueprint for the famous pyramid complex of his successor, King Djoser of the Third Dynasty. In fact, the prototype for Djoser’s complex may even predate Khasekhemwy. When combined with the fact that the Pyramid of Ahmose at Abydos was the last royal pyramid constructed in Egypt, then we are left with the conclusion that the practice of building royal pyramids began and ended at Abydos.

Also not so well known is the significance of the tomb of Senwosret III, which may mark the transition from the Pyramid Age, where kings were buried in a complex much like Djoser’s, to the hidden subterranean tombs of the Valley of the Kings. When understood within its full context, the cemeteries and cultic centers of Abydos were ground zero for practically all of the significant developments in Egypt’s mortuary rituals and practices.

In this article you will be introduced to the various sites where the Penn-Yale-IFA Expedition to Abydos is conducting its work. You will meet the people and learn the significance and implications of their work. Afterwards you will be all the better equipped to answer for yourself—is Abydos the most important historical and archaeological location in Egypt?

Before we delve into the Penn-Yale-IFA joint expedition, lets lay some groundwork by taking a look at Umm el-Qa’ab. Although this location falls largely under the management of the German Archaeological Institute, Umm el-Qa’ab is of extreme importance to Abydos, and is the site that ties the various elements of Abydos into a cohesive whole.

Umm el-Qa’ab

The ancient procession that leads the way from Osiris’ Tomb at Umm el-Qa’ab to the Temple of Osiris lies along a natural fold in the valley formed by a large wadi (canyon) that enters Abydos through the cliffs along its southern border. The ghost of the wadi falls across the low desert and ends at the ancient settlement of Kom es-Sultan, site of the ancient temple of Khentyamentiu, the god of death who preceded Osiris. As Khentyamentiu was later joined with, and eventually absorbed by, the god Osiris, the temple at Kom es-Sultan became the primary center for the Cult of Osiris for all of Egypt.

Umm el-Qa’ab, which is Arabic for “Mother of Potshards,” is located in the high desert where the wadi cuts its way northward from the cliffs and settles into the ancient procession-way. The opening of the wadi and the high desert form the southern boundary of Umm el-Qa’ab, which is bound on the northeast by the Middle Cemetery, and to the north by the North Cemetery.

The burial ground of Umm el-Qa’ab takes its name from the abundant potshards (qa’ab) that covered the plain there, remnants from the annual pilgrimages that occurred from the New Kingdom to the Late Period when offering pots were left for Osiris. It was believed by the ancient Egyptians that the tomb of Osiris was located at Umm el-Qa’ab, and there is evidence that tombs were excavated there during the Twelfth Dynasty in an attempt to locate the tomb. Something about King Djer’s tomb, which became the traditional Tomb of Osiris at around this time, must have impressed the ancient archaeologists.

It has been known since the Nineteenth Century, when Emile Amelineau began excavations at Abydos, that Umm el-Qa’ab was the cemetery for the earliest kings of Dynastic Egypt, although there are earlier predynastic royal tombs in Cemetery U, the North Cemetery. The tombs of six First Dynasty kings and one queen—Djer, Djet, Den, Anedjib, Semerkhet, Qa’a, and Queen Merneith—are located at Umm el-Qa’ab. The tombs of two Second Dynasty kings have also been excavated at Um el-Qa’ab, namely, Peribsen and Khasekhemwy.

One unique feature of First Dynasty (and some predynastic) tombs is the existance of ‘satellite tombs’. In more common parlance, these were graves for human sacrifices. All of the First Dynasty tombs have satellite tombs that were occupied by servants who were intended to accompany the king into the afterlife. Djer had the most—more than 330. One can’t help but wonder if this impressive array of postmortem courtiers may have led the Twelfth Dynasty excavators to conclude his tomb must have been that of Osiris Himself!

The number of satellite tombs decrease toward the end of the First Dynasty, and no evidence for them exists from the Second Dynasty onward. There was some debate over whether the satellite tombs were indeed the scene of ritual human sacrifice or if the king’s attendants were simply buried after their natural death. However, recent evidence seems to settle this grim question. For one, all of the occupants were young and in apparent good health, and showed evidence of strangulation. But more decisive, as pointed out by Dr. David O’Connor in a recent Heritage Key interview, is the evidence that the tombs were all sealed at the same time.

Dr. O’Connor speculates that such ritual death was probably no “horrible imposition” on the courtiers, who would have felt privileged to join their king in his new adventures. However, the effect of being conscripted into an early trip to the afterlife must have had some detrimental effect, because it was clearly abandoned at the end of the First Dynasty.

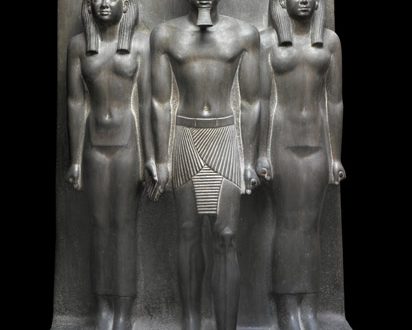

The practice of human sacrifice was replaced by the ritual internment of statues intended to animate in the afterlife to serve the same purpose as their human counterparts. These statues would develop into the shabtis that are so commonly found in Egyptian tombs. Thus, the practice of burying the king with scores of statuettes that were intended to come to life and serve him in the afterlife has its roots at Abydos.

Cemetery B—The Middle Cemetery Project

Cemetery B, the Middle Cemetery, lies just to the northeast of Umm el-Qa’ab, along the ancient procession-way. Originally the burial grounds for predynastic royalty (now often referred to as Dynasty 0), the Middle Cemetery became the burial grounds for non-royal elites during the Old Kingdom Period. Dr. Janet Richards, of the University of Michigan, is currently responsible for excavations in the Middle Cemetery. Dr. Richards’ work is the Middle Cemetery Project of the Penn-Yale-IFA expedition.

The first significant tomb to be excavated at Cemetery B was that of Aha. Now commonly considered to be the first king of the First Dynasty, an honor previously held by Narmer, Aha’s tomb was built complete with wooden funerary shrines and satellite graves for his favorite servants. Once thought to be one massive complex, the site around Aha’s tomb has been differentiated into four Dynasty 0 royal tombs—those of Aha, Iri-Hor, Ka, and Narmer.

Dr. Richards’ work has largely revolved around important Sixth Dynasty officials who were buried around the central part of the Middle Cemetery. Perhaps the most historically significant of these would be Weni the Elder, whose mastaba was nearly one hundred feet on each side and over fifty feet high. Weni the Elder was a governor of Upper Egypt during the Old Kingdom Period, and he left a very detailed autobiography inscribed on the walls of his funerary chapel. The autobiography is important for providing not only details of his official duties, but for giving us a portrait of his everyday life.

In addition to Weni the Elder, Dr. Richards’ team discovered the tombs of two other important Sixth Dynasty elites. One belonged to an official named Nekhty, who held the title of Overseer of Priests, and the other was that of Vizier Iuu, Weni’s father. In 2001 Dr. Richards’ team excavated the chambers and burial shafts of Weni and Nekhty’s complexes and discovered they had suffered considerably during the upheaval of the First Intermediate Period. Nekhty’s tomb had been ransacked and Weni’s was nearly completely destroyed by fire.

Dr. Richards’ work with the Penn-Yale-IFA expedition continues with the on-going work of the Middle Cemetery Project’s survey of the Old Kingdom tombs of the elites. Her excavations of these very well preserved tomb decorations, mortuary items, and statuary help us understand the status of the elites of the Sixth Dynasty. It was local nobility of precisely this type who were increasingly flexing their independence during the Sixth Dynasty and opening the way to the First Intermediate Period.

Cemetery U—The North Cemetery Project

Cemetery U, the North Cemetery, is located due north of Umm el-Qa’ab, across the procession-way from the Middle Cemetery. Used for both royal and non-royal burials during the early predynastic period, the North Cemetery was reserved for the royal predecessors of the Dynasty 0 kings during the Naqada III period, but was again abandoned by these early kings in favor of the Middle Cemetery.

The North Cemetery has been excavated under the Penn-Yale joint expedition since 1966, before being joined by the NYU Institute of Fine Arts. Important work has also been done in this area by the German Archaeological Institute, which under the leadership of Gunter Dreyer excavated the important tomb U-j.

Tomb U-j dates from around 150 years before the time of Aha and is one of the indicators of how developed and consolidated power was even under the predynastic kings. The large 12-chambered edifice contained a wooden shrine, pottery, and goods such as oils that indicate foreign trade was already active during this period. The glyph of a scorpion appears throughout the U-j complex, leading to its owner being dubbed King Scorpion, although it is uncertain whether this was an actual name or part of a title.

More recent work has focused on the Middle Kingdom tombs, of which there are two types. The more elite shaft graves—the luxury models—were constructed with a mudbrick mastaba-type surface building complete with interior chambers and shrines. The economy models—the family minivan class—had a simple pedestal-style surface architecture that was just a couple of feet high. The shafts would typically open into a burial chamber, and there might be several such chambers at different levels of the shaft in the family models. Multiple chapels were often found with shaft tombs containing more than one occupant. All models were oriented to the north.

For the truly frugal there was a surface model—shallow graves dug into the surface stone. These tombs came with or without a wooden coffin, depending on the departed’s funerary budget. They did not have surface architecture, but evidence has been recovered that offerings were left by faithful family members, possibly at makeshift shrines. Like their more expensive cousins, surface tombs were oriented toward the north.

Excavation of the non-royal tombs in the North Cemetery has taught us much about the people of the Middle Kingdom Period. There appears to be no effort to maintain a socially based stratification, with lower and middle-class tombs mixed in with those of the non-royal elites. This indicates non-royals at all levels of social class had similar beliefs about the afterlife, and that even the poor had hopes for a heavenly reward.

Another interesting phenomenon observed in the North Cemetery is that some of the more expensive shaft tombs bore no indicators that their occupants held court or religious offices or titles. This seems to suggest that some Middle Kingdomers were doing quite well for themselves outside of the religious and political professional structures.

The Penn-Yale-IFA Abydos Expedition continues to analyze the mortuary landscape of the North Cemetery under the leadership of Dr. David O’Connor, Dr. Janet Richards, and Dr. Matthew Adams, all of whom have explored various aspects of this ancient graveyard at various times.

The Funerary Monuments of the Early Kings

About a mile north of Umm el-Qa’ab, located prominently on the hills overlooking the site of the ancient town of Abydos, are the remains of large fortress-like enclosures that could very well prove to be the early forerunners of the pyramid complexes of the Third and Fourth Dynasties. The excavation and preservation of the early funerary monuments of North Abydos is the domain of Dr. David O’Connor and Dr. Matthew Adams, of the Penn-Yale-IFA expedition.

These huge enclosures were the location where the mortuary rituals of First and Second Dynasty kings were carried out. The enclosures were both larger and more impressive than the royal tombs to which they were associated, and were the primary statements of royal presence at Abydos during the Early Dynastic Period.

The only remaining cult enclosure is the last and largest, belonging to the last king of the Second Dynasty, Khasekhemwy. The other enclosures appear to have been purposely destroyed. Lack of evidence of erosion and other forms of gradual destruction has led Egyptologists to conclude they were demolished not long after being built. One possibility is they were dismantled soon after the king’s death as a symbolic burial enabling the king to make use of the

shrine in the afterlife. Funerary structures inside Djoser’s mortuary complex at Saqqara were similarly buried after construction to sanctify them for usage in the afterlife. This, however, is far from the only potential link to Djoser.

Khasekhemwy’s cult enclosure, which has been named Shunet el-Zebib in recent times, has drawn many interesting comparisons to the pyramid complex of Pharaoh Djoser at Saqqara. Like Djoser’s complex, which was only built 40-50 years later, Shunet el-Zebib was originally surrounded by a niched enclosure wall. As with Djoser’s enclosure wall, the entrance to Shunet el-Zebib was at the southern corner of the east wall. But most intriguing was Dr. O’Connor’s discovery of the ruins of a square mudbrick-faced mound located within the enclosure exactly where Djoser’s pyramid is located with his own complex.

Dr. O’Conner made yet another discovery strangely reminiscent of the Memphis Necropolis. To the southeast of Djer’s cult enclosure, close to the northeast outer wall of Shunet el-Zebib, fourteen mudbrick-lined boat graves were found, with wooden ships buried inside. Comparison to the boat pits in the shadow of the pyramid complexes of Saqqara and the Giza are inevitable.

The work at North Abydos continues, with Dr. Adams taking charge of preservation efforts. He has discovered that the best means of protecting and preserving the site are to replicate the work of its creators. To that effect new mudbricks comparable to the look and function of the originals are used to shore-up the structure, but at the same time they are not so similar as to be confused with the original material. All restoration work is easily distinguished from the original.

The South Abydos Project

South Abydos is the location of royal burials during the Middle Kingdom Period. Located to the east of the ancient procession and meandering off toward the low desert to the southeast, South Abydos contains several archaeological sites representing major transitions in Egypt’s mortuary practices and traditions. The South Abydos Project of the Penn-Yale-IFA expedition is concerned primarily with two areas—the mortuary complex of Senwosret III in the central valley area, and the complex of Pharaoh Ahmose to the southeast.

The director of excavations at the mortuary complex of Senwosret III is Dr. Josef Wegner of the University of Pennsylvania. A king of the Twelfth Dynasty of the Middle Kingdom Period, Senwosret III constructed a funerary complex at Abydos in addition to a pyramid complex at Dashur. This was not unusual as kings and commoners alike built cenotaphs at Abydos to assure their connection to Osiris in the afterlife. But this was different.

Like other royal mortuary complexes, Senwosret III’s site included a mortuary temple and a mudbrick surface enclosure. But unlike the typical shaft tomb, Senwosret III constructed an enormous subterranean tomb more than 800 feet in length. It was originally believed that Senwosret III was buried in his pyramid complex at Dashur, but Dr. Wegner’s recent work has produced abundant evidence that the tomb at South Abydos was intended as an actual burial place for the pharaoh.

If King Senwosret III was buried at Abydos, then this marks a significant development in royal funerary practices. It would be the earliest example of a king being buried in a hidden subterranean tomb. Unlike shaft burials, in which the kings were buried just several meters below the surface of the earth, Senwosret III’s tomb penetrates 800 feet into a cliff face in a hidden chamber which seems to be an antecedent of the Valley of the Kings burials. Thus, the site of Senwosret III represents the transition from the earlier pyramid complex burials to the Valley of the Kings model of royal burials.

In addition to the tomb, Dr. Wegner continues his work at the Temple of Nefer-Ka, which was the site of Senwosret III’s mortuary cult, and the excavation of the town of Wah-Sut. The site of Wah-Sut in South Abydos is one of the most unspoiled examples of a town from the Middle Kingdom Period. So far excavations have revealed six elite houses and the mayoral residence, and work at this promising site is really just beginning.

For more information about the complex of Senwosret III and the South Abydos Project in general, don’t miss Heritage Key’s Exclusive Interview with Dr. Josef Wegner.

Further to the southeast lies the complex of Pharaoh Ahmose and his family, excavation of which falls under the expert direction of Dr. Stephen Harvey, a long-time Abydos veteran also from the University of Pennsylvania. If the cult enclosure of Khasekhemwy in North Abydos represents the first royal pyramid complex in Egypt, then Ahmose’s complex represents the last.

Ahmose’s complex is dominated by a mound of sand and stone named Kom Sheikh Mohammad in recent times, and which was once a limestone-faced pyramid. Ahmose’s mortuary temple consisted of a central pillared court behind a mudbrick pylon and is decorated with scenes of his mortuary cult and battle scenes of his victory over the Hyksos. The latter are believed to contain the earliest depictions of chariots in Egyptian history. There is a smaller temple nearby that may have been dedicated to Ahmose’s queen, Ahmose-Nefertari.

To the west of the pyramid lie the ruins of mudbrick domiciles that probably housed the builders of Ahmose’s complex and the priests and servants of his mortuary cult. In 2006 Dr. Harvey’s team excavated the remains of a small work area on the eastern side of the pyramid. In addition to the ruins of a bakery and other workshops, Dr. Harvey discovered archaeological remains of the builders’ work areas that will add to the understanding of how the pyramid and temples were constructed.

To the south of the pyramid is a mastaba-like shrine Ahmose built in honor of his grandmother Tetisheri, who contributed substantially to making Ahmose’s ousting of the Hyksos possible. When her son, Tao II, initiated the rebellion against the Hyksos Tetisheri kept the royal court in order, functioning practically as coregent. She has been credited for setting the example for the powerful Eighteenth Dynasty queens who would follow her. At the end of a hallway in her shrine Ahmose erected a beautiful stela proclaiming her virtues.

To the south of Tetisheri’s shrine is a subterranean tomb which may have served as Ahmose’s tomb, although it is rough cut and gives the impression of having been hastily constructed. The mudbrick-lined shaft winds into a large central hall containing eighteen pillars. At the recent symposium at the Penn Museum, Dr. Harvey argued that Ahmose was most likely buried in his tomb at Abydos, which remained a center of his worship at least until the Ramessid Period.

Nearly a mile away, to the southwest and at the base of a high cliff, are the remains of another curious structure. This edifice consists of a terraced mudbrick wall upon which another terrace is supported by a limestone wall. There is no sign of further construction on top of the second terrace, although there are several rooms at the southeastern end of the terraces. Miniature stone and ceramic vessels, along with wooden model boats, have been recovered from the top terrace. The function of this structure has not yet been identified.

Dr. Harvey continues his work at South Abydos for the Penn-Yale-IFA joint project. His discoveries are changing how we understand the transition from the Memphite mortuary traditions to the Theban traditions, with Abydos being center stage for these developments.

Abydos Today

Many of the world’s great religions include pilgrimages to their most holy sites. The Hajj, the Fifth Pillar of Islam, is the obligation of every able-bodied Muslim to travel to Mecca at least once in their lives. Modern Christians and Jews make pilgrimages to Jerusalem. Various locations within India and Nepal are sites of pilgrimages for Buddhists and Hindus alike.

Abydos was the destination of pilgrimages from predynastic times until well into the Christian era. Today, tourists make the pilgrimage to Abydos, which is a little off the beaten path from most Egyptian sites which tend to hug the Nile River. Once there they visit the impressive temples of Seti I and Ramesses II, and to view the Osireion—once the Holy of Holies for the Cult of Osiris.

But the real wonders of Abydos are being unearthed out in the desert, a bit of a hike from the parking lot where the busses let you out. High up at Shunet el-Zebib and out among the cliffs where Ahmose’s complex lie are where the history of pyramid complexes is being unraveled. The dusty low desert holds the clues of how the upper, middle, and lower classes interacted in both life and death. The mudbrick honeycombs of Umm el-Qa’ab and the Middle Cemetery hold the architecture and artifacts that show the transition from human to representational sacrifices in royal complexes.

Dr. Wegner has stated that “Abydos is a major site with on-going work and new discoveries every year,” and that we can hopefully expect another symposium on the Penn-Yale-IFA Abydos Expedition very soon. I am unaware of any members of the joint expedition going so far as claiming, as I did in the opening of this article, that Abydos may be the most important site to Egyptology today.

What do you think, now that you have seen the evidence? The Comments section below await your own reflections and opinions!