The New Acropolis Museum is arguably the most high-profile building to go up this decade (since we in New York are still peering into a big hole in the ground that is supposed to produce a new World Trade Centre). Essentially a smack in the face of the British Museum’s argument that Athens has no suitable venue in which to house the Elgin Marbles, it’s also the most controversial. I spoke to Bernard Tschumi, the outspoken architect who designed this extraordinary building.

The New Acropolis Museum is arguably the most high-profile building to go up this decade (since we in New York are still peering into a big hole in the ground that is supposed to produce a new World Trade Centre). Essentially a smack in the face of the British Museum’s argument that Athens has no suitable venue in which to house the Elgin Marbles, it’s also the most controversial. I spoke to Bernard Tschumi, the outspoken architect who designed this extraordinary building.

Replacing the smaller old Acropolis Museum, the purpose-built new museum ensures that architectural treasures too delicate to be left out on the weather-beaten Parthenon and surrounding buildings will be protected from further harm. Athena has a shiny new modern pied-à-terre on the Acropolis; the Olympian Gods can continue to wage their Gigantomachy out of the rain, and the original Parthenon, considered to be a symbol of the culmination of Doric Order and the peak of Ancient Greek art, now has a new answering structure in glass and concrete to safeguard its threatened treasures and encourage a slew of new visitors to appreciate them.

The Ghost in the Museum

Of course the main reason the Museum, opened June 21, continues to be in the news is because of what’s not there. In case you’ve been living on a desert island for the last thirty years, Greece is missing some of the Parthenon’s metopes – narrative panels carved from marble that formed a high, outward-facing frieze around the building when it was first built in the early part of 5th century BC.

This is a long story that doesn’t reflect especially well on anybody, except possibly Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin, who removed about a

quarter of the original panels to Britain in 1806, at the agreement of the Ottoman Empire, which was then occupying Athens, as well as rather a lot of Europe besides. The reason anybody with half a brain, the means, and the will might have done the same was because the Ottomans had not exactly been taking care of the Parthenon. In fact, half of the metopes had already been destroyed when they imaginatively used this eighth wonder of the world as a munitions dump, and it was blown up, in 1687, during an onslaught by the Venetians.

So in my opinion Lord Elgin was really doing everyone a favor when he took them down and had them packed off to the British Museum – it’s surprising he didn’t take them all. Some of them ended up in France too, and are now in the Louvre. It’s a long story.

Anyway, the Ottomans finally got sent packing (although not before they’d made the Parthenon into a mosque and built a minaret on top of it), and Greece began a long slow pull up from a decidedly third-world country whose capital city sported some of the worst air pollution in the world, to a thoroughly pukka member of the European Union and perfectly

capable of looking after its own ancient stuff, thank you very much. This is where the Brits (along with the French) started to look less like noble custodians of another country’s priceless treasures, and began to get a bit slippery. The marbles are ours, they said, because the Ottomans were legally entitled to give them to us, since they were the occupying owners of the country at the time. Oh, and anyway, you can’t look after them properly because Athens is one big belching traffic jam. And, anyway, you haven’t gotten anywhere to put them, have you?

All the time, anyone acquainted with the Parthenon knew that refusing to reunite the British and French metopes with the Greek ones was like having to go to three different cinemas in three different countries to watch different bits of Citizen Kane. It made no sense at all.

Insult and Injury

Or, as Bernard Tschumi, the architect who designed the New Acropolis Museum, likes to put it, it’s like having the head of a statue in Athens, the torso in London, and the legs in Paris. You can throw all the legal argument you like at it, but it’s still flat wrong. “It’s insulting to the artist and to the period to break it apart,” he said, during a face-to-face interview in New York City, where his firm is based.

Or, as Bernard Tschumi, the architect who designed the New Acropolis Museum, likes to put it, it’s like having the head of a statue in Athens, the torso in London, and the legs in Paris. You can throw all the legal argument you like at it, but it’s still flat wrong. “It’s insulting to the artist and to the period to break it apart,” he said, during a face-to-face interview in New York City, where his firm is based.

Sometimes, unfortunately, there are still cases when a nation’s artifacts need to be taken off site and out of harm’s way – the National Museum of Afghanistan in Kabul springs to mind. “It’s never a case of absolutes,” said Tschumi. “Never an ideological statement. That’s why I don’t like the nationalistic approach. It’s on a case-by-case basis. But at the same time, certain artefacts belong in the same place.”

Obviously, the completion of the New Acropolis Museum building, which has had mixed but generally good reviews, knocks out the argument that there’s nowhere to put the Elgin Marbles. Plastercast replicas of the pieces are already up in place, pointedly bright white next to the yellowed marble of the real thing.

The Greeks have been publicly calling for the return of the Marbles since Melina Mercouri, then Minister for Culture of Greece, started a campaign in the early 80s, and before even then, the Greek government held its first competition to design a museum to put them in. Several competitions over the decades produced no results because of arguments over site, size, and so on. Then finally, a competition announced in 2001 resulted in a jury backing the Tschumi design and construction documents were drawn up. It wasn’t plain sailing from there, however.

“There were a lot of polemics at the time,” Tschumi said. “Greeks seem to like polemics.” Tschumi saw a lot of time and energy wasted in arguments over the museum, especially the requirement for Museum Director, Professor Dimitrios Pandermalis, to give personal testimony at more than 100 court cases. The cases ranged from local groups who didn’t want a big modern building in their neighbourhood, to archaeologists who opposed building a structure on an important archaeological site, to “politicians fighting other politicians and using whatever means they can find,” Tschumi said. All this delayed construction, especially above the archaeological remnants, since that took longer for court approval. “The building was conceived to protect those remnants; not only protect them, but stage them in a new way. We wanted them to be part of the experience of the museum,” he continued.

Custom Built

I asked: was it difficult to build a museum without knowing exactly what was going to go in it? Tschumi said that, quite the contrary, this was a museum with unusually predictable contents. “We knew exactly what might be in it. We know exactly what’s in the British Museum,” he said, with a gleam in his eye. “So many museums, like the Guggenheim in Bilbao, are built with no idea of what will go in them.”

exactly what’s in the British Museum,” he said, with a gleam in his eye. “So many museums, like the Guggenheim in Bilbao, are built with no idea of what will go in them.”

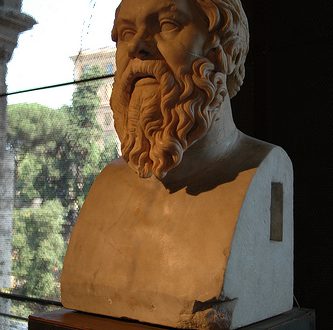

Nevertheless, there were some new discoveries in the archaeological dig at the site between the design and the building stage, including a 4th century BC bust of Aristotle. The design employs stilts to minimize the museum’s footprint, affording a view through glass floors of the site’s deeper history. Luckily, this feature was sufficiently flexible to accommodate the new discoveries.

There’s Always one

Meanwhile, other disagreements raged on – the building was too modern, the building was too expensive, the building was ugly, and so on. I asked Tschumi if he felt himself at this time to be at the centre of a controversy. “Well, the building was at the centre of a controversy,” he said. “We stood at the side, protected by Professor Pandermalis. It was better that we concentrate on that than be involved with shouting.” He raised his palms in the air and shrugged. “All through this I had no doubt that the design was the right one; that it was possible to build something at the site in a beautiful manner.”

Putting old and new together in a thought-provoking way was important for Tschumi. “I have often argued that a city is a mound of successive layers. Instead of juxtaposing them, we were layering them, floating one above another. One of the most important aspects of architecture is that it be able to bring together things of different times,” he explained. “A

building is not of one single moment in time. It’s expensive; it takes time; it lasts a long time. The role of architecture is to stage and give credit to other times, including the past. So I believe that ancient artefacts are even more beautiful the way they are staged here than if they were in the open air with a fence around them.”

There’s an important dialogue to be had between the old and the new, and his design helps put new verve into the discussion, Tschumi believes. “The Museum shows how the contemporary can give, retroactively, a new value to the historical and architectural.”

Obviously, the Museum has also put given new life to the dialogue about whether to reunite the Parthenon metopes.

“I am absolutely convinced the marbles are going to come back, but don’t ask me when, because it maybe needs a rethinking of what is a museum in the twenty-first century. It’s not necessarily the same as a museum at the end of the eighteenth century,” said Tschumi.

The great museums of the world used to play a crucial, irreplaceable role in discovering and protecting items of universal cultural value, and then giving them maximum exposure to a public hungry for news and experiences of other lands and times – even offering a whistle-stop tour of the important civilizations that preceded us. But cheap travel, instant communication, and increasingly sophisticated methods of reproduction (such as Virtual King Tut, for example) have changed the game forever.

“At this time, physical proximity is not so important; the context is important,” said Tschumi. “I, as an architect, do not need to see the cathedral at Chartres and some incredible mask from Mali next to one another to be able to judge the nature of their respective cultures.”