Young Howard

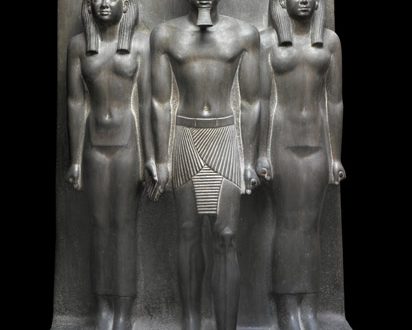

Howard Carter was a talented child. Home-schooled in London, and encouraged by his artist father, he had plenty of time to practice his love of drawing and painting. And when his father went to work in Norfolk for archeaologist William Amherst, Carter caught probably his first glimpse of the kind of ancient Egyptian artefacts that would fascinate him for the rest of his life.

Life in Egypt

Carter’s talent for drawing and his interest in Egyptian antiquities lead William Amherst to arrange an interview for him with Percy Newberry who had been working on a site at Beni Hasan. Carter was appointed as a trainee tracer and in 1891, when he was just seventeen, Carter travelled to Egypt with Newberry. His job as a junior artist with the Egypt Exploration Fund, working on the excavation of Beni Hasan and El-Bersheh, must have been a dream come true for the young enthusiast.

And Carter was good at his job. The next few years saw his career and reputation grow. In 1892, he joined Flinders Petri at el-Amarna. Ironically, Petrie thought Carter would never become a good excavator, but Carter proved him wrong when he unearthed several important finds. Petrie was a demanding teacher, but Carter was a determined man. He became an archaeologist but kept up his artistic skills by sketching many of the unusual artefacts found at el-Amarna.

Carter was later appointed Principle Artist to the Egyptian Exploration Fund for the excavations of Deir el Babri, and the following five years saw him perfecting his drawing skills with the epigraphic recording of the temple there. He also improved his excavation and restoration techniques. Carter was a perfectionist, meticulously documenting his findings. This may have lead to his reputation of being somewhat introverted and a bit of an autocrat.

Defence Of The Guards

At the age of 25, in 1899, Carter was offered the job of First Chief Inspector General of Monuments for Upper Egypt by the Director of the Egyptian Antiquities Service, Gaston Maspero. His responsibilities included supervising and controlling archaeology along the Nile Valley. He worked at Thebes and Edfu and installed electric light at Abu Simbel. Theodore Davies recognised his talents and together they discovered the tombs of Thutmose I and Thutmose III in the Valley of the Kings.

Carter held this position until an unfortunate incident occurred between drunken French tourists and Egyptian site guards at Saqqara. He had allowed the guards to defend themselves against the violently abusive tourists, who subsequently went through high officials demanding Carter made a formal apology. Carter’s refusal to comply tarnished his name, and he was transferred to a less important post in the Delta.

He resigned from the Antiquities Service the following year. With his professional career in ruins, Carter spent the next few years working as an artist, supplementing his earnings with some tour guide work and antique dealing.

The Golden Years

Carter’s luck changed when he was introduced to the fifth Earl of Carnarvon by Gaston Maspero. Carnarvon agreed to finance Carter, centring their work first at Thebes and later, in 1912, to the Delta. In 1914 they receive a licence to dig in the Valley of the Kings from the Egyptian Antiquities Service but the outbreak of the First World War stopped excavations.

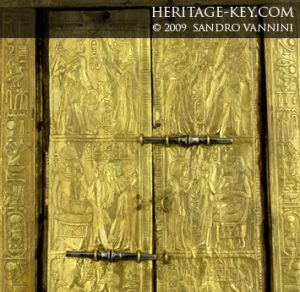

In 1917 Carter convinced Carnarvon to finance his search for the tomb of Tutankhamun. It took another five years and a final beg for money from Carnarvon before Carter found the elusive tomb. On November 4th, 1922, the first steps leading to Tutankhamum’s tomb were revealed.

Howard Carter’s name was now permanently in the history books and he became something of a celebrity. Work on clearance and recording the tomb contents continued until the concession ran out in 1929. The Tomb of Tut.ankh.Amen, by Howard Carter and Arthur C. Mace, appeared in three volumes between 1923-33. Failing health and other commitments, however, meant Carter never published a detailed scholarly account of the tomb.

The Sunset Years

Carter retired from archaeology and took up collecting Egyptian antiquities. Toward the end of his life, Carter could often be seen at the Winter Palace Hotel at Luxor, sitting by himself in wilful isolation.

After forty active years in Egypt, Carter returned to London in 1932. He died on 2nd March, 1939 of lymphoma at the age of 64. The London Times, which just a few years earlier had made him a household name, announced his death along with the obituaries on page 16.

Carter is buried in Putney Vale Cemetery, London. The epitaph on his gravestone reads: “May your spirit live, May you spend millions of years, You who love Thebes, Sitting with your face to the north wind, Your eyes beholding happiness”.