Almost 32,000 years ago, man got its first puppy. Today still, humans have a special connection with animals, regardless if they are sitting on our laps, or – point on our plates. Why is it in our nature to accept of all kinds of creatures into our families and homes? What came first, the carbonade that would stay put, or the steadfast companion in the pursuit for game? And what if our first prehistoric attempts at art were no mindless doodling or sacred effigies, but an early publication of ‘Useful Beasts for Dummies’?

Almost 32,000 years ago, man got its first puppy. Today still, humans have a special connection with animals, regardless if they are sitting on our laps, or – point on our plates. Why is it in our nature to accept of all kinds of creatures into our families and homes? What came first, the carbonade that would stay put, or the steadfast companion in the pursuit for game? And what if our first prehistoric attempts at art were no mindless doodling or sacred effigies, but an early publication of ‘Useful Beasts for Dummies’?

In a paper describing a new hypothesis for human evolution based on our tendency to nurture members of other species, palaeoanthropologist Pat Shipman argues that the human-animal link goes well beyond simple affection. She proposes that, over the last million years, the interdependency of early man with other animal species the animal connection” played a crucial in human evolution.

“Establishing an intimate connection to other animals is unique and universal to our species,” said Shipman. “No other mammal routinely adopts other species in the wild no gazelles take in baby cheetahs, no mountain lions raise baby deer,” Shipman said. “Every mouthful you feed to another species is one that your own children do not eat. On the face of it, caring for another species is maladaptive, so why do we humans do this?”

Shipman, a professor of biological anthropology at Penn State University, suggests that the animal connection was prompted by the invention of stone tools 2.6 million years ago. “Having sharp tools transformed wimpy human ancestors into effective predators who left many cut marks on the fossilised bones of their prey,” Shipman said.

This putour ancestorsin direct competition with other carnivores for prey.Humans who learned to observe and understand the behaviour of both their potential prey and competitors, were more successful at obtaining large amounts of meat without a doubt an evolutionary advantage.

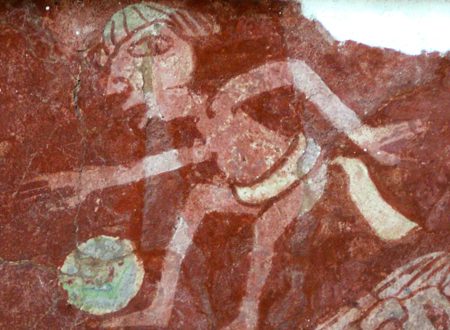

The majority of early prehistoric art depicts animals. Shipman sees this as evidence that the evolutionary pressure to develop an external means of storing and transmitting information symbolic language came primarily from the need to share and handle what we knew about other species.

Though we cannot discover the earliest use of language itself, we can learn something from the earliest prehistoric art with unambiguous content. Nearly all of these artworks depict animals. Other potentially vital topics edible plants, water, tools or weapons, or relationships among humans are rarely if ever shown,” Shipman explains.

Shipman concludes that detailed information about animals became so advantageous that our ancestors began to nurture wild animals a practice that led to the domestication of the dog about 32,000 years ago.

Surely, if insuring a steady supply of meat was the point of domesticating animals, as traditionally has been assumed, then dogs originally ferocious wolfs – would be a very poor choice as an early domesticated species? “Wolves eat so much meat themselves that raising them for food would be a losing proposition,”the professorpoints out.

Instead, Shipman suggests, the primary reason for domestication was to transform the animals we had been observing for millennia into living tools during their peak years, then only later using their meat as food. “As living tools, different domestic animals offer immense renewable resources for tasks such as tracking game, destroying rodents, protecting kin and goods, providing wool for warmth, moving humans and goods over long distances, and providing milk to human infants” she explains.

Domestication is a process that takes generations and puts selective pressure on abilities to observe, empathize, and communicate across species barriers. Once accomplished, the domestication of animals offers numerous advantages to those with these attributes.

“The animal connection is an ancient and fundamentally human characteristic that has brought our lineage huge benefits over time,” Shipman summarises. “Our connection with animals has been intimately involved with the evolution of two key human attributes tool making and language and with constructing the powerful ecological niche now held by modern humans.”

Pat Sherman’s paper is to be be published in the August 2010 issue of the journal Current Anthropology. In addition, Shipman has authored a book for the general public, titled The Animal Connection.