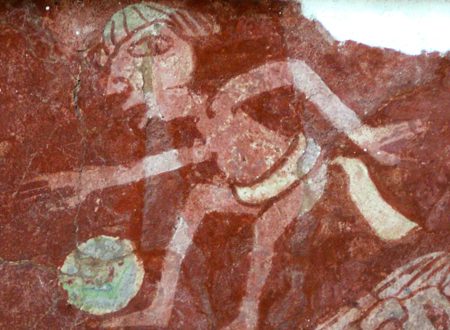

The Brooklyn Museum holds 7 human and over 60 animal mummies in their collection. We know already quite a lot about their human mummies, but now Lisa Bruno tells us more about the animal mummy research project at the Museum in an informal presentation for the Museum’s ‘1stfans’. The Brooklyn Museum’s conservator Lisa Bruno talks about what an object conservator exactly is (and how to become one), the travelling exhibition ‘To Live Forever’ which is coming to the Brooklyn Museum February 2010 and the research the Getty Institute did on the ‘red mummy’ Demetrios – once thought to be a female.

And that’s not all, in her presentation Lisa Bruno also gives an insight in the extensive research on animal mummies: humanoid mummies containing both ibis and cat bones ibis bones*, crocodile mummies, fake animal mummies, resins used in mummification, blunt trauma on cats and poisoned crocodiles, economics of animal mummification, metal animal coffins and even a snake mummy!

Not all animal mummies consist of a whole animal, and it’s quite well possible this was a question of economics. There were many ways to make an animal mummy, but the most traditional way follows the way human mummies – don’t try this at home – are created:

- Make an incision, take out the internal organs.

- Dry the mummy using natron salt (sodium carbonate).

- Seal and preserve the tissue with resinous materials like tree sap, waxes or coal tar.

- Wrap in linen bandages.

Why did the Egyptians make animal mummies? Common thought by the public is that they were cherished pets, or grave gifs that could be useful in the afterlife. But that would not explain why hundreds and hundreds of animal mummies were found in Egypt, and some are actually in dedicated cemeteries. So might the cat mummies have served a more spiritual purpose? Likely, if you see that the mummy of a snake-killing egyptian mangoes was associated with a goddess of protection, and at some point animal mummies were even obligatory to honour the rulers of ancient Egypt.

talks about the animal mummy research project

at the Brooklyn Museum

As more institutions begin to study their collections of ancient animal mummies, there seems to only be more questions as to what these differences in mummification styles and animal species might actually mean.

In the months that have followed this presentation, the Brooklyn Museum’s conservation lab has continued to examine and x-ray the collection of animal mummies. They have enlisted the help of a radiologist at The Animal Medical Center Dr. Anthony Fischetti. Recently Anthony and a colleague visited the museum specifically to look at the x-radiographs of the cat mummies. In examining the radiographs, the veterinarians were able to confirm that the animals in the x-rays were in fact cats, and were able to give information regarding possible age. Depending on the size and shape of the skull and teeth, they were sometimes able to suggest whether the mummified cat was more likely a species of domesticated cat (Felis silvestris) or a wild species (Felis chaus).

The Brooklyn Museum also donated two long bones from their cat mummies to the ‘feline genome project’ run by Dr. Leslie Lyons for the University of California. The project is looking into what ancient DNA can tell us about current domestic cat populations. We’re curious, especially as people despite extensive research still not agree when the first ‘wolf’ was turned ‘dog’.