What Have the Etruscans Ever Done for us?

“What have the Romans ever done for us?” is a classic question from Monty Python’s Life of Brian (and possibly my favourite Roman-related screen moment of all time). But the Romans too could have asked themselves: “What have the Etruscans ever done for us?” The list would be almost as long as the one reeled off to the irascible John Cleese: language, architecture, engineering, gods, rituals – and much more – were all handed down in one shape or form to the Romans from their Etruscan ancestors. But despite the Etruscans’ advanced culture and technical abilities, surprisingly little is known about them. Even the questions of who they were and where they came from haven’t been answered with any great certainty by modern historians.

Where did They Come From?

So what do we know about the origins of this mysterious culture? There are several theories about their origins. According to the Greek historian Herodotus of Halicarnassus, writing in the fifth century BC, the Etruscans once lived in Lydia, in Asia Minor. They then travelled to the Italian peninsular at some time before the eighth century BC, colonising central Italy along the Tyrrhenian coast. But conflicting theories suggest that the Etruscans were an autochthonous tribe – claiming that they originated where they lived, in central Italy.

A further idea has been spawned by an engraved stone found in a warrior’s tomb on the Greek island of Lemnos. The Lemnos Stele dates from 600 BC and is inscribed with a language very similar to Etruscan. It was discovered along with pottery and weapons that are also strikingly similar to early Etruscan examples, which led historians to believe that the Etruscans had strong ties with Lemnos in the northern Aegean sea, as well as with Asia Minor. However, whether they originated on Lemnos or emigrated there (either from Italy or from Asia Minor) is in question.

The truth probably combines elements of each of these theories – there is no way of finding out for sure since hardly any Etruscan texts have survived. For now, the most plausible theory is that the Etruscans were indeed an indigenous tribe of central Italy, and were greatly influenced by the Greeks and Lydians from Asia Minor who emigrated and traded with Etruria between the 10th and the fifth centuries BC. One of the most famous Etruscologists, Massimo Pallottino, who wrote the introduction to DH Lawrence’s 1927 collection of travel essays Etruscan Places, supported this idea.

Etruria’s Power and Expansion

Before 750 BC, Etruria stretched from the Tiber in the south up to the Arno in the north and was contained by the Tyrrhenian sea in the west and the Appenine mountains along Italy’s spine. Between 750 and 500 BC, the Etruscans were at their zenith. They were technically and culturally advanced, enabling them to prosper from trading with other populations in the Mediterranean, as well as from their advanced knowledge of metal extraction, agriculture, crafts and engineering. This new-found wealth fuelled their expansion and, with little opposition from local Italic tribes, the way was clear for them to expand and eventually dominate an area up to the Po River valley in Italy’s north. While the Umbrian and Picene tribes south and east of the Tiber were initially able to hold the Etruscans at bay, the latter were eventually able to push their borders southwards towards Campania as well.

Etruscan Cities and Cities of the Dead

The Etruscan civilisation was a mainly sea-faring culture – often referred to as a thalassocracy by scholars, although they were probably thought of as a bunch of pirates by their Greek and Carthaginian rivals in the Mediterranean. Most of their important towns were near to the Tyrrhenian coast, including (modern names in brackets): Tarchna (Tarquinia), Caisra (Cerveteri), Velch (Vulci), Vetluna (Vetulonia), and Alalia (Aléria on Corsica’s eastern coast). There were also several ports including Fufluna (Populonia), Pyrgi (Santa Severa) and Alsium (Palo), which were important strategic centres for trading and fishing. The Etruscans were able to dominate this area of the Tyrrhenian sea during the seventh and sixth centuries BC, although the Greeks still kept control of southern Italy and Sicily.

To the north, the Etruscans settled in the Villanovan centre of Marzabotto and Felsina near modern-day Bologna. They established ports on the Adriatic which traded with the Dalmatian coast, and also interacted with La Téne cultures in mid-Europe.

In central Italy the main Etruscan cities were: Viterbo, Veii, Velzna (near modern-day Bolsena or Orvieto), Clevsin (probably Chiusi), Curton (Cortona), Arretium (Arezzo), Felathri (Volterra) and Faesulae (Fiesole). In the south, Capua and Nola were the main Etruscan towns, although Etruscan objects and constructions have also been found at Herculaneum and Pompeii (for example, the House of the Etruscan Column at Pompeii, which has an Etruscan pillar incorporated into the wall of a Roman house).

The most important evidence that we have today of Etruscan culture comes from the tombs and necropoli that are found sporadically around Etruria. The most famous examples are the necropolis at Tarquinia (with its painted tombs) as well as the Banditaccia necropolis at Cerveteri, which shows their rock-carving expertise, as well as the extent of Etruscan city-planning (even the city of the dead is planned along an organised grid with streets). Other Etruscan necropoli exist near the towns of Veii and Vulci. The painted, decorated tombs and their rich contents (most of which are now in museums) show that Etruscan culture was flourishing.

The Etruscans’ Rise and Fall

From the end of the eighth century BC and during most of the seventh century, the Etruscans underwent an ‘orientalising’ period, during which Etruscan art and craftsmanship were heavily influenced by Greek colonists from the east. A good example of this is the Regolini-Galassi tomb at Cerveteri, which originally contained many Egyptian and Greek objects. While the Greeks, particularly those of Magna Grecia, were rivals of the Etruscans, there was still cultural interaction. There is evidence of Greek and Phoenician settlements in Etruria as well as a great deal of Attic pottery found at Etruscan tombs.

Shortly after the orientalising period, during the middle of the sixth century, the Etruscans achieved the peak of their strength, but it wasn’t to last long. The Greek colonies to the south started to pose more of a threat to the Etruscans and to counter this the Etruscans formed an alliance in 545 BC with the Carthaginians.

Ten years after this alliance was forged, in 535 BC, the Etruscan and Carthaginian alliance fought the Greek Phocaeans at the battle of Alalia, an important naval battle fought off the coast of Corsica. The Etruscans won this battle only to start fighting again in 524 BC, when they attacked Cumae, a Greek settlement in Campania. Much to the Etruscans’ surprise, they were the losers this time. Another defeat followed in around 505 BC when the Etruscan king Lars Porsenna was defeated at the battle of Aricia.

But worse was to come: the Etruscans came into conflict with the Greeks once more at Cumae in 474 BC. Another heavy defeat led to them losing their dominance of the Tyrrhenian sea. At around this time Celts from northern Italy also invaded, pushing the Etrurian boundaries back south of the Po, while local tribes from Campania also overthrew Etruscan rule: Etruria seemed to be shrinking and the Etruscan star was waning. But there was a bigger threat looming: a small city state to the south of Etruria had grand ideas.

End Game: The Spread of Rome

The legend of Rome’s beginnings is generally accepted as having one, or maybe both, feet firmly planted in mythology. Did anyone really believe all that about the princess impregnated by Zeus and the twins brought up by a she-wolf? A far more likely version of events points to the Etruscans and their expanse southwards in the eighth century BC. There is evidence to suggest that the Etruscans were present on the Palatine and Capitoline Hills at this time. When they first came to the Tiber, they found nothing more than a collection of small hill-top villages made up of shepherds’ huts. They united and organised these disparate settlements into a prosperous town, building an important sewer, the Cloaca Maxima in 578 BC, which drained the marshy land between the Palatine and Capitoline Hills (the future Roman Forum), and also building city walls around the Capitoline Hill. From this it is clear that the Romans owe their very inception to the Etruscans.

During the eighth to the sixth centuries BC, Rome was a city within Etruria. While Rome traditionally had seven kings between 753 and 509 BC (again, this story owes more to legend than documented evidence), these kings are thought to have governed the city under Etruscan rule. In fact the last three kings of Rome were, at least partially, Etruscan. At around the same time that the Etruscans were losing their battles with the Greeks in the south, Lucius Junius Brutus saw Rome’s chance and overthrew the last Etruscan king, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus. Rome became an independent republic in 509 BC.

From the fifth to the third centuries BC, Rome expanded throughout the Italian peninsular and after Etruria’s defeats against the Greeks between 524 and 474 BC, the Etruscan civilisation retracted into a group of disunited city states unable to put up much resistance against the Romans. One of the most well known battles is the defeat of Veii in 396 BC – this Etruscan town eventually fell to Rome after a 10-year siege. The Roman domination of Etruria’s towns marked the end of the Etruscan civilisation, although the Etruscans continued to live in these towns as part of the Roman republic.

Since the pre-republic city of Rome was partially formed, built and ruled by the Etruscans for at least a century, it is reasonable to think that there was a certain intimacy and understanding between these two cultures. When the tables turned and Rome became the dominant population, they conquered Etruria without the aggression and brutality that they showed elsewhere (eg, at Carthage). This is maybe an indication of the cultural debt that the Romans felt they owed to their ancestral neighbours.

So What Exactly Did the Etruscans Ever do for Rome?

The influence of the Etruscans ran throughout Roman culture. Here are some examples:

- Many Etruscan religious customs have been absorbed into Roman (and consequently Christian) practices, such as the use of the priest’s Littus (a curved staff), which later became the Christian bishop’s staff.

- There are significant influences on Christian dress and rituals, derived from Etruscan religious customs. Purple was a sacred colour used by Etruscan priests and this use continued in the form of the purple toga designated for the emperor of Rome, and for the cardinal’s robes in the church.

- The Etruscans had their own calendar divided into 12 sections, which would have provided a basis for an early Roman calendar – although it is possible that both Etruscan and Roman calendars are based on the Greek lunar calendar.

- Etruscan gods took on Roman guises, for example the Etruscan gods Tinia, Uno and Menrva were all given a new lease of life under their Roman incarnations of Jupiter, Juno and Minerva.

- The Etruscans had advanced knowledge of metallurgy, hydrolics and divination, which they passed on to the Romans.

- Although the Etruscan language has been only partially decoded, many Etruscan words became part of the Latin language of Rome, and so find themselves in modern romance languages. Etruscans also had their own form of writing, which may have influenced the Latin script.

- The Etruscans were skilled architects and engineers and, while the Romans became far more famous for their ingenuity and construction, they learned many of their skills from their forebears the Etruscans.

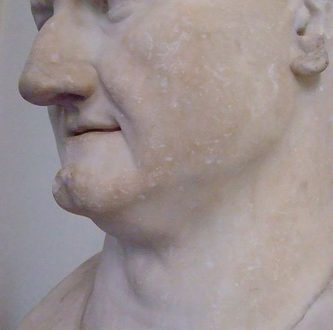

However, the Romans didn’t absorb all aspects of Etruscan culture. One major difference is the position of women in Roman times compared to Etruscan women in Etruria. The latter were able to hold important positions in society and socialised with men on an equal basis. The status of the couple is shown by many of the sarcophagi found in the Etruscan tombs at Cerveteri and Tarquinia – for example the Sarcophagus of the Spouses shows a young couple laughing and enjoying a feast in each other’s company, with the woman depicted with as much individuality and personality as her companion. By Roman times, women were credited with a more subservient role in society and were expected to obey the male head of the household, the paterfamilias. In this respect, the Romans seem to have been influenced more by their Greek trading partners rather than their Etruscan neighbours.

It is frustrating that there is not more evidence of the Etruscan culture today. We know that the emperor Claudius, also an avid historian and writer, wrote a history of Etruria in 20 volumes, although none of it has been preserved. Most of the information we have about the Etruscans comes from what can be gleaned from their tombs. With new tombs coming to light periodically in Tuscany, Lazio and Umbria, we can only hope that more evidence will one day be discovered so we can answer some the questions that still remain about the Romans’ mysterious forefathers.

Photos by: Sebastià Giralt (top); Museo Civico Archeologico di Sarteano (middle); @@@@@ (bottom).