18 to 20 year old male, Caucasoid, cause of death: unknown. It’s a brief that wouldn’t have sounded unfamiliar to Jean-Noël Vignal – a forensic anthropologist who works with police to create likenesses of murder victims at the Centre Technique de la Gendarmerie Nationale in France – when it landed on his desk in 2005. Yet the tragic young man in question on this particular occasion was no ordinary subject – he was the most legendary ancient Egyptian that ever lived.

Tutankhamun, a Pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty, died mysteriously in 1323 BC. His body lay undisturbed for over 3,200 years until it was famously discovered in the Valley of the Kings by Howard Carter in 1922. 83 years later – as part of a wider five-year endeavor to scan and preserve the ancient mummies of Egypt, many of which are crumbling – Tut’s remains were fed into a portable CT-scanner (a special kind of X-ray machine) which captured 1,700 digital cross-sectional images of his mummified corpse from top to bottom.

It was with these scans in hand that Vignal set to work generating a modern reconstruction of Tutankhamun’s face. The resulting bust has been widely accepted – after being validated by a pair of further similar reconstruction projects by separate American and Egyptian teams – as being as accurate as possible a rendering of the boy king’s image just before his untimely death. But it has stirred up some controversy too.

Tut’s Return

Tut’s Return

The project to scan the remains of Egyptian mummies was led by Zahi Hawass – secretary general of Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities. It was the National Geographic Society that selected and put up the funding for the French team, helmed by Vignal, to use the scans to bring Tut’s face back to life.

The depth of information that Vignal was able to derive about the pharaoh from the scans was remarkable. As well as providing the basic information about the size of his head, they also provided sufficient evidence for him to determine the shape and contours of many of Tut’s facial features – his mouth, nose and chin. Vignal was even able to offer an accurate assessment of the thickness of Tutankhamun’s skin.

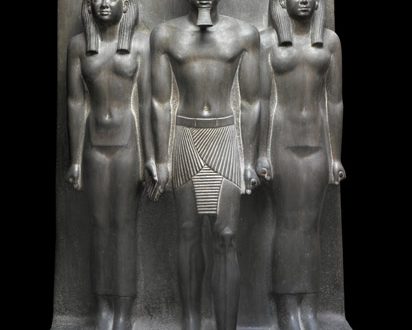

Vignal used this information to create a rough plastic version of Tut’s skull. The next phase of the project was carried out by Elisabeth Daynès, a top forensic sculptor based in Paris, who – using Vignal’s plastic skull as her base – began moulding layers of clay onto it to establish a life-like artistic image. Ancient wooden statues of Tutankhamun were used as sources for hints at some of the features that couldn’t be determined from the scans; finishing touches of silicone “skin”, glass eyes, some dots of hair and a flourish of eyeliner completed the pharaoh’s new face.

So What Did Tutankhamun Look Like?

For a figure with such a powerful and enduring historical legacy, Tutankhamun actually didn’t have the strongest of features. His cheeks were chubby, he had a large overbite (apparently something of a characteristic among the pharaohs of the 18th dynasty), his nose was sloping, his chin weak and his scalp weirdly elongated. Overall, his appearance was baby-faced and effeminate.

Consider too that he wasn’t the tallest of chaps (judging by his corpse, Tut probably stood around 5-foot-6 in his heels) nor the best built, and you have to say that it was lucky he was king of Egypt really, because otherwise he wouldn’t have been much of catch. He was healthy though at least, a rare thing in an age when people were dropping dead like flies from an unknown disease.

Win or Bust

The reliability of Vignal and his team’s rendering of Tutankhamun’s face was put to a stern test by their backers in the National Geographic Society. To ensure that the boy king couldn’t be picked out in an identity line-up, two further teams of forensic anthropologists were put on the case, entirely independently of the French endeavour.

The job of bringing Tut to life for a second time was entrusted to an American, Susan Antón – associate professor of anthropology at New York University. She received assistance from Bradley Adams of New York City’s Chief Medical Examiner’s office. To further make certain that her Tutankhamun leaned as close as possible to the hard evidence of the scans – rather than any popular images or knowledge of the pharaoh – Antón was made to work blind, with no idea in advance of who her subject was. A bust based on her results was created by forensic artist Michael Anderson of Yale’s Peabody Museum.

The third and final project to recreate Tutankhamun’s face was carried out by an Egyptian team. Unlike Antón, they were given a heads-up on who their famous subject was. To the elation of all involved, when the three busts were placed side by side, despite some differences in details all three broadly looked remarkably similar.

King Tut Whitewash?

King Tut Whitewash?

Plenty of artistic license has obviously been applied to process of reconstructing Tutankhamun’s face from the CT-scan evidence, the first and most famous bust of which was put on the front cover of the June 2005 edition of National Geographic Magazine. Yet, from looking at contemporary representations of the pharaoh on various artefacts, the similarities are there for all to see.

One aspect of the French bust has been a subject of some controversy however – the colour of Tut’s skin. No amount of forensic evidence can determine the tone of the pharaoh’s flesh, so the team based the colour of his synthetic skin on a mid-range of the various different shades found in modern Egyptians today. This sparked anger among some Afrocentrists, who claimed that the bust made Tutankhamun appear to be white, despite this not being the prevalent skin tone of either modern day Egyptians, nor their ancient ancestors. King Tut exhibitions in Los Angeles and Philadelphia were even picketed by black demonstrators, protesting against the image.

National Geographic executive Terry Garcia defended the bust by saying “North Africans, we know today, had a range of skin tones, from light to dark. In this case, we selected a medium skin tone.” Dr Hawass responded to the protests with the statement: “Tutankhamun was not black, and the portrayal of ancient Egyptian civilisation as black has no element of truth to it”. The argument continues to run.

Case Closed

The CT scan did prove one thing conclusively. Two other X-rays had been carried out on Tut’s corpse prior to the 2005 investigation – in 1968 and again in 1978. The former, by a group from the University of Liverpool, revealed trauma to the back of the skull – an injury that could have been caused by accident, or by assault. Theories abounded that Tut had been murdered, either by his successor to the throne Ay, his wife Ankhesenamen or even his chariot driver.

The 2005 scan revealed no further evidence of suspicious circumstances surrounding the damage to Tut’s skull – more likely it was inflicted during the embalming process, or as a result of haphazard treatment of the corpse by Carter and his team in the 1920s. Indeed, attention became focused much more so upon a newly discovered fracture of Tut’s leg, giving rise to speculation that it may have been an infection caused by this injury that actually killed the boy king. Despite techniques that wouldn’t have looked out of place in an episode of CSI: Crime Scene Investigation, the oldest homicide case is still open.