“There is no other site like it,” states the introductory paragraph on the website of the Amarna Project – the body which, since 2005, has been responsible for excavations and research at Tell el-Amarna, the short-lived capital city of the “heretic pharaoh” Akhenaten (who may well have been King Tut‘s dad) in the 14th century BC. As a living site, Tell el-Amarna is perhaps unparalleled in all of Egypt in terms of scale, ready accessibility and quality of preservation.

“There is no other site like it,” states the introductory paragraph on the website of the Amarna Project – the body which, since 2005, has been responsible for excavations and research at Tell el-Amarna, the short-lived capital city of the “heretic pharaoh” Akhenaten (who may well have been King Tut‘s dad) in the 14th century BC. As a living site, Tell el-Amarna is perhaps unparalleled in all of Egypt in terms of scale, ready accessibility and quality of preservation.

Professor Barry Kemp – of the University of Cambridge – is the director of the Amarna Project, and also the chairman of the Amarna Trust, a UK registered charity which provides most of the funding for the project. Kemp has directed excavation and archaeological survey at Amarna for the Egypt Exploration Society since 1977, and is one of the world’s leading authorities on the ill-fated ancient Egyptian city.

It in a wide-ranging interview with Heritage Key, Kemp explains what makes Amarna so important, and details the history of excavations there. He also reveals the latest news on the construction of a brand new visitor centre at Amarna, and gives us a heads-up on plans for future investigations and study at the site.

HK: Can you sum up for us first of all what is so very special about Amarna?

BK: The uniqueness of Amarna is twofold. Firstly, it was created – so its founder the Pharaoh Akhenaten tells us – to be a sacred place. It was to be sacred in an absolute way: not for pilgrimage, but as a place where the sun-god (the Aten) would feel at home. It was thus a place of communication with the divine. The choice of the location and the layout are therefore crucial to understanding what was in the king’s mind. Later religions, including those that are with us now, came to centre on words. In the world of ancient Egypt, however, material expression of belief counted for a lot more. The study of material remains, the essence of archaeology, correspondingly counts for more, too. Amarna itself is central to the beliefs that Akhenaten promoted.

Secondly, although the building of a residential city of several tens of thousands of people – that was necessary to support the court and service Egypt’s administration (read about daily life in Amarna here) – was incidental to Akhenaten’s vision, it has survived as a major source of information on the way that the people of ancient Egypt lived. It was laid out on what has remained a tract of desert, and this has ensured excellent conditions of preservation. It was abandoned within a short time (maybe fifteen years) so that it comes close to preserving a snapshot of buildings and artefacts. Its scope extends across the houses of poor and rich, across palaces and temples and tombs.

HK: Give us a brief overview of archaeological work carried out at Amarna prior to the start of the Amarna Project. How much had already been excavated?

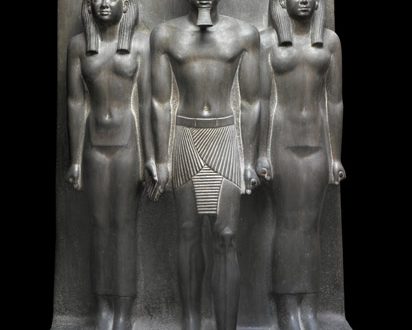

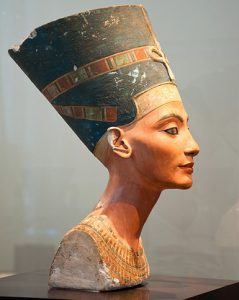

BK: Amarna was the object of extensive archaeological clearances carried out in the first part of the 20th century. An expedition of the Deutsche Orientgesellschaft had excavated between 1911 and 1914, entirely within the housing areas. This reflected an interest in domestic architecture. Amongst the objects found was the painted Bust of Queen Nefertiti, in the house of a sculptor.

Between 1921 and 1937, a British-based expedition, of the Egypt Exploration Society, took up the work and extended it to all parts of the site, including the central area of palaces and temples. By the time the expedition finished, most of the royal buildings had been cleared, and around half of the residential city. These clearances were done rapidly and, to some extent, should be regarded as providing preliminary accounts.

HK: Tell us about the background of the Amarna Project – how did it come together, and how did you come to lead the project?

BK: Early in my working life, I was invited to prepare a paper for a seminar entitled ‘Man, settlement and urbanism’, to be held in December 1970 at the Institute of Archaeology of London University. Writing it brought me to see that archaeology could be better used to address fundamental questions about urban society in ancient Egypt, and that Amarna was the best place to tackle this on a significant scale. Eventually, I asked the Egypt Exploration Society if they would support a new survey of Amarna. They agreed, and in 1977 I started. After two seasons of mapping they agreed to fund an excavation. In 2005, as a result of changes in British government funding to archaeology abroad, I set up the Amarna Trust (a registered charity) to raise funds specifically for Amarna. The Amarna Project now runs independently, funded largely by the Trust.

HK: What are the main aims of the Amarna Project? And – for you – what have been the most important discoveries made by the Amarna Project to date?

BK: The main research goals are a better understanding of why Amarna has its particular appearance (bearing in mind that it is a projection of Akhenaten’s thoughts), how it functioned as a major city and how its sizable population adapted to living there. We seek integration, between evidence from the site and ideas drawn from the general history of cities and from the workings of Egyptian society in the New Kingdom, the period in which Amarna is set. Individual discoveries of the kind that people associate with archaeology, fairly rare even in the days of the grand-scale clearances of the past, are not the proper measure of success.

HK: What have you been concentrating on in your latest season of fieldwork?

BK: Current fieldwork embraces surveying and excavation. The main excavation at present is a large cemetery of the ordinary people who lived in the city. The remains of the individuals, which are preserved only as bones not mummies, are an invaluable guide to health and living-standards, and the style of burial reveals aspects of belief and behaviour not otherwise accounted for. The burials were extensively robbed not long afterwards, so much work is needed to piece individuals together and to draw out a general pattern of how the burials were originally made.

HK: Give us a sense of the scale of the Amarna Project – the number of people involved, the size of the area excavated etc?

BK: The project has no full-time staff other than a local caretaker who looks after the expedition house. We maintain an office in Cairo not far from the Egyptian Museum. The research is done by experienced archaeologists and by other experts interested in material that accumulates in the storerooms maintained at the house. Fieldwork is supported by groups of men from the local villages hired for limited periods, usually of between one and two months at a time.

The cemetery is a long narrow site along the sides of a wadi, extending for a distance of around 600 metres but only some 60 metres wide at the maximum. Excavation is contained within grids of five-metre squares and is necessarily slow to ensure full recovery of material. At the end of four seasons the total number of squares excavated is 27.

HK: What are the unique challenges of the Amarna Project? I imagine the sheer size of the area you’re investigating must present many problems in itself?

BK: Amarna, like all ancient sites in Egypt, belongs to the Egyptian government and is administered by the Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA).

This body encourages foreign missions to assume some degree of responsibility for conservation and general care of the places where they work, in conjunction with their own staff, who include local site custodians. Excavation and research, therefore, are only parts of a wider mission that the project has.

The ancient city extends intermittently beside the river bank for approximately 7.5 kilometres and has two modern villages incorporated within it. We have chosen individual buildings for cleaning and repair, currently the North Palace. Like the rest of what survives it is constructed from sun-dried mud bricks. For our repairs we make new bricks to the ancient size, but the material is inevitably subject to decay from the elements so that continuing maintenance is needed.

While a select few of the ancient buildings deserve to be repaired and left open to public view, the huge areas of houses excavated in the early part of the last century would be better re-buried. This is the only suitable way to preserve what is left of them. Re-burial on the scale needed, however, is a huge task that requires an increase in funding. The modern villages are developing fast, and the refuse that they produce increasingly intrudes upon the site. So a low-level collection of rubbish is now a further task to organize.

HK: A reconstruction of the city was exhibited in 1999. Where did the idea for the reconstruction come from, and how accurate is it?

BK: The model of the city (or at least the central portion of it) was made for a major Amarna exhibition, Pharaohs of the Sun, organized by the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the idea of its ancient Egypt curator, Rita Freed. The exhibition opened in November 1999 and subsequently traveled to other cities in the USA, and finally to the Netherlands. The idea of the model came from UK architect Michael Mallinson. He and I worked on the design details through the preceding summer, as it was being constructed by a London model-making company, Tetra. Large parts of the model cover excavated ground, the plans of which provided the initial source. How the buildings looked can be reconstructed with some confidence from a variety of supplementary sources. Areas of the western side, however, and especially the part beside the river now covered by fields, have to be conjectural as do certain aspects of the Great Palace.

HK: To look at the pictures of the reconstruction, it could almost be a model of a modern Egyptian town. Was Amarna quite advanced architecturally for its time?

BK: The resemblance to a modern town of Egypt or of other countries arises very much from the way that the residential areas were created without reference to a pre-existing plan.

Much of the city organised itself. Its layout of houses and streets must be the result of a process of local negotiation as the large households of the officials who ran Akhenaten’s government moved in and settled down within a short period of time. The result is a continuous and merging series of villages.

The court occupied the centre, but there were no commercial or manufacturing districts. This is where Amarna differs from cities as they later developed. What were to become independent sectors of society were then embedded within the lifestyle and responsibilities of the same class of officials.

Manufacture and distribution were shared between the state and the official class, and so were ubiquitously present throughout the city.

HK: Where is the reconstruction model now? Can it still be viewed somewhere?

BK: After the exhibition closed the model was shipped to Egypt and received by the SCA. It is now in the secure storeroom at the expedition house, awaiting cleaning and minor repairs. The hope is that it can be displayed in the Amarna Visitor Centre that is now nearing completion.

HK: Digital reconstructions of heritage sites are becoming increasingly common in the 21st century (visit Heritage Key’s own virtual Amarna). Are there any plans for a digital reconstruction of Amarna, and do you think such a thing could prove useful in teaching people about the site?

BK: Partial digital reconstructions have been made, to accompany film documentaries, but we do not have access to them, and they are very generalised. To make the kind of digital reconstruction familiar from, say, the Lord of the Rings, would entail a budget far in excess of anything that we can aspire to. So the answer is: no. With lower budgets it is preferable, in my opinion, to construct actual models. A new set of models of individual buildings has been made (by the firm Eastwood Cook of London) for the Visitor Centre.

HK: What’s the latest on the Amarna Visitor Centre. How close is it to opening, and what can we expect from the museum when it opens?

BK: The idea of a Visitor Centre at Amarna goes back many years. Construction began in 2005. It is a project of the SCA, to designs by Mallinson Architects.

For a short time it was upgraded to be an actual museum, most of the material coming from the expedition stores. We have no masterpieces, but in their place we have a mass of material that illustrates aspects of life in the city. Being often fragile and mostly fragmentary the pieces would have required the services of a professional display team.

Eventually we realized that this was not feasible on the resources available, and it has reverted to being a Visitor Centre, dedicated to explaining the nature of Amarna, the record of its archaeology, and how we can reconstruct from this a working picture of the city. The building is finished. The installation of the displays will begin early in 2010.

HK: The Bust of Nefertiti is perhaps the most famous artefact discovered at Amarna – would you like to see it displayed in the Amarna Visitor Centre one day? Do you think the bust should and/or will ever be returned to Egypt?

BK: The painted Bust of Nefertiti with its instantly recognizable profile has been adopted as a symbol of tourism in Egypt, and as a symbol of Minia Province in which Amarna lies. It does seem to me perverse that the original is not in Egypt. If it were returned, people would quickly get used to it. But I doubt if its return is imminent. (Follow these links to hear some of the arguments for and against the Bust of Nefertiti being returned to Egypt from Germany).

HK: For how much longer will the Amarna Project be digging at Amarna?

BK: Like all foreign expeditions in Egypt, the Amarna Project works with an annually renewable permit from the SCA.

Their authority in these matters is absolute, but they recognise that foreign expeditions have a useful role to play in research and in helping to look after ancient sites. Digging is only a part of what we do. Sites undoubtedly benefit from the presence of long-running projects which commit a substantial amount of time each year to being present, and which direct a portion of their resources to assisting in caring for the site. It helps, in a general way, to persuade local people that the site does have some significance beyond its being in the ownership of the SCA. So the project has no set end point.

HK: What areas to you intend to concentrate on in the next few seasons of fieldwork?

BK: The cemetery excavation will continue for a few years yet. We are also beginning a major new survey of the site, using geophysical sensing equipment, to try to establish more clearly what lies in the large areas that remain unexcavated. This is being done as a field school jointly organized with the University of California, Los Angeles, and the University of Arkansas. But in the background the work of archiving and establishing a better paper record of what has been found at Amarna is also an important priority.

HK: Finally, Amarna is clearly a very important site, yet in the grand scheme of ancient Egyptian sites, it’s not nearly as well known and recognised as, say, Giza or The Valley of the Kings. Do you think it deserves to be, and perhaps one day will be?

BK: Within a short time after Akhenaten’s death, the extensive stonework used for the main royal buildings was removed, to be used as building material elsewhere. Amarna the city has, therefore, no standing monuments, although the decorated rock-cut tombs of Akhenaten’s officials that lie in the cliffs behind are an impressive spectacle. What is mostly to be seen is a flat, sanded-up but very picturesque archaeological site. The visitor needs to have done some homework and to be prepared to use their imagination. It is far less self-revealing than the pyramids.

Amarna is one of a wide spread of sites in Middle Egypt, each having its own charm and interest. As a group, however, they need more time and organisation to reach than the sites close to Cairo or at Luxor. Access is getting easier, but it is likely that most visitors, whether foreign or Egyptian, will come only if they have developed a particular interest.

Among visitors to Amarna are those who come for a spiritual return, for whom the visit is more of a pilgrimage, who find that Akhenaten offers a message with which they can engage. Their numbers are perhaps on the increase. Who can tell how much of a trend this will be?

A twice-yearly Amarna Project newsletter, Horizon, can be downloaded from the websites www.amarnaproject.com and www.amarnatrust.com (where you can also make a donation to the trust).