The Edwin Smith Papyrus was this year touted as “the birth of analytical thinking in Medicine and Otolaryngology,” in the medical journal The Laryngoscope. Along with a collection of other fascinating papyri, the script gives an incredible insight into the knowledge, skills, and procedures of ancient Egyptian medicine, and offers some tips on how to treat trauma issues, such as a man with a massive gouge in his head.

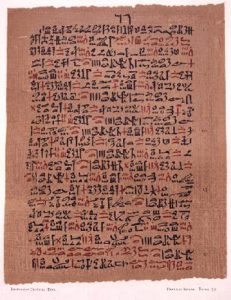

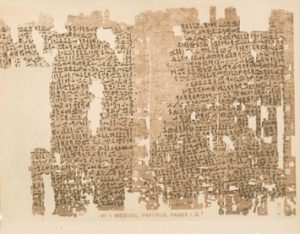

Much of what we know about Egyptian medicine comes from roughly a dozen medical scrolls that have survived. The oldest one is the Kahun Scroll, dating to 1820 BC, which focuses in Gynaecology. The two longest, and arguably most important scrolls, are the Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus (ca. 1,500 BC) and the Ebers Papyrus, which dates to the reign of Amenhotep I (1526-1506 BC).

The Edwin Smith Papyrus focuses on healing trauma wounds. One recent study suggests that it wasn’t written by a doctor at all, but by a metalworker training to be a battlefield medic.

doctor at all, but by a metalworker training to be a battlefield medic.

Perhaps the most unusual scroll is “The Brooklyn Papyrus on Snake bites,” written during the 30th dynasty (380-343 B.C.) or early Ptolemaic times. As its name suggests it concentrates exclusively on how to treat a snake bite. There is no indication in this papyrus that the Egyptians knew the modern form of first aid treatment, which consists of using a tourniquet or cutting open the bite wound and taking out the poison.

It has one treatment that would have reduced the swelling – bandaging the wound with salt. On the other hand its main treatment isn’t very practical – digesting a mix of onions, salt, sam-plant and beer. Doctors today know that while this will make a patient throw up but it won’t take care of the poison.

Your Friendly Neighbourhood Swnw

We know that Egypt had a hierarchy of medical doctors. In Medicine in the days of the pharaohs Bruno Halioua and Bernard Ziskind write that the lowest ranked physician was called a swnw. A swnw answered to an inspector of sorts, a sehedj swnw (in the middle kingdom this was changed to imy-r-swnw). This person in turned answered to a chief physican, who had authority over a broad geographical range, a wer swnw.

At the very top was the personal physician to the pharaoh, wer swnw mehw shena. There was also a ranking system for junior physicians who served in the pharaoh’s palace. Although we know that doctors existed, we have yet to find any artefacts that can unquestionably be called medical instruments.

Life and Death in the Ancient ER

The document that has made the biggest impression on modern day doctors is the Edwin Smith Papyrus.

It’s a 17 page papyrus that focuses on how to treat trauma wounds, such as skull fractures. It lists 48 cases of trauma and talks about how to treat it and what the prognosis is.

There is very little magic mentioned.

The cases start at the top of the head and work their way down to the arms and spine. Dr. John Nunn, a medical doctor and author of Ancient Egyptian Medicine, says in his book that this is the same order followed by Gray’s Anatomy.

In each of the cases there are four prognoses. An “ailment I will treat,” indicates that it is considered non life-threatening; an illness that “I can contend,” means that it is uncertain whether the patient will live or not. “Not be able to treat,” means that either the patient is mortally ill (in which case palliative care is recommended) or it means that the doctor cannot do anything whatsoever about it (best to leave the patient alone, but the patient may yet live).

The papyrus also contains information on how to determine what is wrong with the patient and then match it with the correct treatment. For example, case five describes a patient with a head injury and comminuted/depressed/compound skull fracture. In Ancient Egypt this would usually be a mortal injury. The case reads (from a Burridge/Sanchez 2007 translation):

Regarding an oozing wound from a gash/cut in his head, that has smashed in his cranium

—Then you have to probe his wound.

—Should you find that fracture that is in his skull deep and sunken under your fingers,

—and a swelling which is over it protrudes,

—and he bleeds from his nostrils

—and his ears,

—and he suffers stiffness in his neck,

—and has found he is unable to look at his shoulders and (down at) his chest.

Then you are to say about him: “One who has an oozing cutting wound in his head, which has penetrated to the bone and smashed in his cranium, who suffers from stiffness in his neck: (This is) a medical condition you will not be able to treat.”

Do not bandage it.

—Secure him to his resting place, until the time of his crisis passes.

Patching up the Poorly

Treatments for conditions where the patient may live included simple bandaging, wound stitching, antiseptics (ie- honey and ox bile) and simple physical procedures such as setting fractures and dislocations.

For example, according to the papyrus the patient does stand a chance of surviving a head injury with a frontal stab wound penetrating the air sinus. The case reads as. (Again, from a Burridge/Sanchez 2007 translation):

Medical instructions for an oozing gash/cutting wound in his head penetrating to the bone, and perforating the membranous lining of his cranium.

—Then you have to probe his oozing wound, that is greatly disturbed because of it.

—Then you are to make him raise his head,

—and it is painful for him to open his mouth

—and his heart/mind is feeble in speaking.

—If you observe his spittle hanging from his lips, not having fallen to the ground,

—while he bleeds from his nostrils and his ears,

—and he suffers stiffness in his neck,

—and he has found he is unable to look to his shoulder joints and his sternum. Then you are to say about him:

“One suffering from an oozing gash/cutting wound in his head

—penetrating to the bone,

—and perforating the membranous lining of his cranium.

—the ligaments (cords) of his jaw are contracted,

—while he bleeds from his nostrils

—and his ears,

—and he suffers stiffness in his neck,

(This is) a medical condition with which I can contend.”

As soon as you find that man, the ligaments his jaw contracted,

—you then have to place on him, something that has been made hot, until he is comfortable: “a roll of cloth for his mouth,”

—then you have to bandage him with oil, and honey dressing until you know that he has passed the crisis.

Now Wash Your Hands

The Egyptians recognized that certain substances had what we would call anti-bacterial properties. The Edwin Smith papyrus recommends honey and ox bile as two substances that would aid a patient’s recovery. This is just like how a doctor today recommends cleaning out a minor wound using soap.

This may seem like a minor thing. But don’t forget, modern day public health agencies spend millions of dollars in ad campaigns encouraging people to wash their hands and clean cuts. Thousands of years of PR and we still haven’t got the message.

In addition the Egyptians developed names for different body parts Including htyt (throat), wdd (gall bladder) and nnsm (spleen).

My Swnw Prescribed me…

The Egyptians used a wide variety of herbal remedies, some of which worked better than others. As Lisa Manniche writes in An Ancient Egyptian Herbal, the Egyptian repertoire includes bandaging a broken bone with acacia, gum and water, using onions to repel snakes and using Leek and fresh urine for poor night vision… none of which are to be tried at home, kids.

There are a large number of these ancient Egyptian pharmaceutical concoctions known to us today. Some of which (such as honey as an antibacterial) would certainly would be useful. Other techniques, such as using Crocodile dung as a contraceptive, would do little more than make the patient vomit. On the other hand, a vomiting lover covered in cow dung sounds like a pretty effective contraceptive to me.