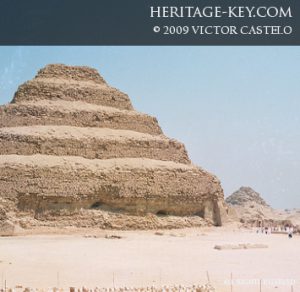

Saqqara, located 40km south of Cairo, was a vast, 6km-long necropolis for the ancient capital of Memphis during the 1st and 2nd dynasties. It is most famously recognised for its step , built for the 3rd Dynasty pharaoh Djoser (2635 – 2610 BC) – but houses thousands of ancient burial sites, with many more submerged beneath the unerring depths of the desert. It stands as not only a memoriam to the time in which it was developed, but also as a yardstick against which all future Egyptian funerary ceremony would be placed.

The City of the Dead

Saqqara was originally built on the entrance to the Nile Delta, immediately west of Memphis – the new capital city of the empire. Its first tombs were built at the start of the 1st Dynasty (ca 3100 BC), on the ridge of the desert plateau. However the early Saqqara did not garner royal attention until the 2nd Dynasty when Boeser (Hotepsekhemwy) and Ninetjer became the first kings interred there. Until then the necropolis had been reserved for highly though-of artisans and nobles.

Saqqara was originally built on the entrance to the Nile Delta, immediately west of Memphis – the new capital city of the empire. Its first tombs were built at the start of the 1st Dynasty (ca 3100 BC), on the ridge of the desert plateau. However the early Saqqara did not garner royal attention until the 2nd Dynasty when Boeser (Hotepsekhemwy) and Ninetjer became the first kings interred there. Until then the necropolis had been reserved for highly though-of artisans and nobles.

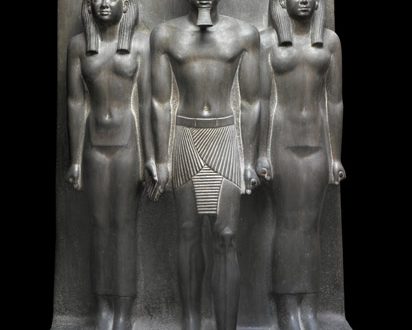

A large number of the earliest graves excavated at Saqqara (many, many more are still hidden beneath the desert sand) are mastaba tombs, which have preserved a valuable early insight into Egyptian religion. The mastaba is essentially a stone block rising from the sand, beneath which the deceased, inside a wooden coffin, would be placed down a deep and narrow shaft which would then be covered over with rubble. There was then a small chapel built into the mastaba with a false door at which the deceased’s family would pay their respects and make offerings to the gods. Another room – the Serdab – would contain a statue of the dead person which would then become inhabited by the Ka portion of the soul.

Changing Beliefs

The discovery of so many mastabas at Saqqara has allowed experts to witness at close hand some of the most prominent religious beliefs of the ancient Egyptians. They believed that the soul was divided into five parts: Ren, Ba, Ka, Sheut and Ib. Hence there was a great emphasis placed upon the longevity of body parts, so that all five could be reunited in the afterlife. Early Egyptians were frequently embalmed and preserved; though mummification was usually reserved for nobility. Saqqara’s reuse over hundreds of years has allowed Egyptologists to chronicle the changing burial practices of the empire throughout its history.

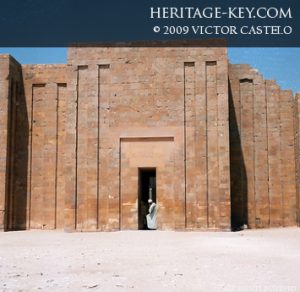

Further excavations have revealed that the Serdab disappeared towards the end of the Old Kingdom (ca 2250 BC), and that the funerary inscriptions plastered all over earlier mastabas were more muted than before. Face masks, the likes of which would reach a zenith in that of Tutankhamun, became common; as did a standardised coffin. By now the great s of Saqqara had been built for some time, with Djoser’s step taking pride of place. Not only was it the largest and oldest stone structure in Egypt, Djoser’s vast mausoleum included the staggering now-restored entrance gate and an ornate Serdab. Through a peep hole, visitors could make offerings to Djoser’s funerary statue. Other s, many of which have now been reduced to rubble, include that of Userkaf (2465 – 2458 BC); Teti I (2345 – 2333 BC); and Pepi II (2278 – 2184 BC; disputedly the longest reign of any monarch in history). Many minor royals are also interred, with mothers, daughters, sons and grandchildren all giving historians a better idea about the complexities of Egyptian sovereignty.

Not only was it the largest and oldest stone structure in Egypt, Djoser’s vast mausoleum included the staggering now-restored entrance gate and an ornate Serdab. Through a peep hole, visitors could make offerings to Djoser’s funerary statue. Other s, many of which have now been reduced to rubble, include that of Userkaf (2465 – 2458 BC); Teti I (2345 – 2333 BC); and Pepi II (2278 – 2184 BC; disputedly the longest reign of any monarch in history). Many minor royals are also interred, with mothers, daughters, sons and grandchildren all giving historians a better idea about the complexities of Egyptian sovereignty.

New Kingdom Discoveries

Undoubtedly the greatest find at Saqqara from the New Kingdom period is the tremendous Serapeum, discovered by Auguste Mariette in 1851. The oldest work in this subterranean temple dates back to Amenhotep III (1391 – 1353 BC), and was where the Apis bulls; anthropomorphic embodiments of the primordial god Phtah. Phtah was later assimilated by Osiris, the god of the underworld – to whom Rameses II and several Ptolemaic kings added to the building. Thus through the Serapeum, experts can map out the changing religious beliefs of the ancient Egyptians, as well as burial techniques.

Mummification by this point was, of course, institutionalised – yet many bodies have been uncovered in Saqqara which were only interred in simple limestone graves. This gives another edge to the site, in the fact that not only kings, queens and nobility could book a place there. Later tombs also frequently included the Book of the Dead; an addition which was made almost prerequisite by the Ptolemaic Period.

Into the Future

As Egypt was defeated and ruled over by Persians, Greeks and Romans, its religions changed dramatically. Yet Saqqara’s use was never neglected – and many intriguing developments were made in burial techniques of the time. As Rome advanced, so the number of funerary ornament diminished – and inscriptions were often made in either Greek, or Egyptian, or a combination of the two.

Then as the Copts found Christianity, tombs reflected the precarious nature of Egyptian religion. Mummification was still common, and models of women, an important pre-Christian symbol of fertility, are usually found in Coptic graves – and all the way up to the Islamic era. Yet crosses and Christian inscriptions also frequent these grave, culminating in an odd compromise. Yet when Islam took hold of Egypt the whole tradition changed, with burials leaving aside the iconography and richness in favour of simple Islamic inscriptions.

Hundreds, perhaps thousands more graves are yet to be discovered at Saqqara – and archaeologists from all over the world flock to the site all year round, attempting to discover the next piece of the ancient Egyptian puzzle. Thus Saqqara is effectively an archaeologist’s playground – and will no doubt continue to map out Egypt’s illustrious past through the vastness of its use over time.