Two British film-makers have discovered what they believe to be the source of the 1,900-year old aqueduct built by the emperor Trajan in the early second century AD. The underground chambers were found and filmed after some years of research into Roman hydraulics by the documentary-makers Ted O’Neill and his father Michael O’Neill. According to Ted, it took some perseverance to find the location, which was hidden beneath a disused church some 30-40km north-west of Rome. Despite difficulties and delays in getting access to the site, the O’Neills were finally able to enter the underground chambers of the church in…

-

-

An illegal Roma gypsy camp might be one of the last places you’d expect to find yourself on an expedition in search of an ancient Roman bridge. But this is what happened to Professor Hans Bjur and his colleagues as they were researching their project on the historical and modern context of one of Rome’s oldest roads. As they made their way through a more neglected corner of Rome’s Ponte Mammolo suburb, they followed the directions to where the bridge should have stood, only to find themselves in the midst of a temporary settlement. While the Swedish researchers were the…

-

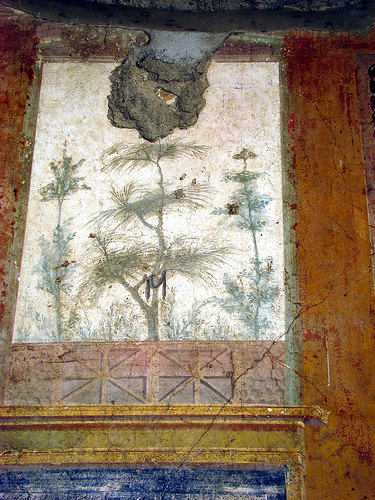

A precious Roman wall painting, stolen from the site of an ancient villa near Pompeii, has been returned to Italy, after 12 years circulating on the nebulous antiquities market. The fragment of plaster fresco originally came from a Roman villa at Boscoreale, just outside Pompeii, and was reported stolen from an archaeological warehouse at Pompeii in 1997. The fresco is a typically Pompeian scene showing a woman dressed in green carrying a dish or tray against a cream background, surrounded by a deep red frame. Another part of the fragmented wall fresco, depicting Dionysos, was recovered from a London art…

-

Humans have always fought each other, but the written narrative of warfare begins about 6,000 years ago with documents detailing a conflict between Elam and Sumer (modern-day Iran and Iraq). Since then military history has been dominated by the official story of leaders and their strategic political and military decisions. Wars have rarely been narrated by the ordinary foot soldier, pilot or sailor. A notable exception to this is the fragmentary records from Vindolanda, some of which give us a soldier’s eye view of army life at a Roman fort between 90 and 120 AD. Information that we can glean…

-

First of all google sent a man on a bicycle around Stonehenge to capture the ancient site in virtual mode for Street View. Now it’s the archaeological site of Pompeii that’s online, allowing Internet users to take a 360-degree tour of the ancient Roman town destroyed by Vesuvius’s eruption in 79 AD. The town’s statues, temples and theatres, as well as close-up views of individual houses and shops are all now visible on Street View, allowing armchair tourists – if that is you, did you try King Tut Virtual already? – to satisfy some of their curiosity about the site…

-

The red carpet was rolled out yesterday at one of Rome’s more unusual archaeological sites, while a discreet police presence also surrounded the visit of the president of the Italian Republic, Giorgio Napolitano to Palazzo Valentini. President of the Province of Rome, Nicola Zingaretti, called it an historic day, as Palazzo Valentini prepared to open its doors to visitors to the Roman archaeological complex and multi-media museum beneath it opening today for a limited time to the public. Zingaretti said: It is a unique place, where cultural heritage comes together with a structure in every-day use. The occasion for Napolitano’s…

-

Historians and archaeologists are having to rethink the history of Roman Wales, as the foundations of what is very likely to have been a Roman villa have been discovered at Trawsgoed, about eight miles from Aberystwyth. As many as 21 Roman villas are known in south Wales, but until now archaeologists didn’t believe that the Romans had built villa-sized dwellings as far north as Aberystwyth, in Ceredigion. In fact, this could be Ceredigion’s first Roman villa, according to the archaeologists working for the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments in Wales (RCAHMW). The realisation was made this summer…

-

Tutankhamun, or King Tut as he’s affectionately known, was the boy king who ruled Egypt during the New Kingdom’s 18th dynasty, from 1333 to 1324 BC. In life he wasn’t the most important or memorable of Egypt’s pharoahs, but in death he’s become the one pharoah everyone’s heard of. His death at the age of 19 has been the topic of much discussion (You can watch last week’s video on the mystery of King Tut’s death here) and he was buried in the Valley of the Kings, on the west bank of the Nile near Luxor (ancient Thebes). His tomb…

-

The first century BC Roman poet Catallus has been making the headlines this week more than 2,000 years after he penned his erotic body of work known as the Carmina. One poem from the Carmina, Catallus 16, begins with the explicit line Pedicabo ego vos et irrumabo – literally translated by The Guardian (who go on to question the BBC’s reluctance to offer a translation and send the reader to check out the full text on wikipedia instead) as “I will bugger you and stuff your gobs.” These Latin words were written in an email by a London business man,…

-

In the small town of Casola di Napoli, about three miles south of the archaeological site of Pompeii, sheer chance has brought to light an archaeological discovery as well as some unanswered questions. A lorry driver was manoeuvring his van when he managed to cause some subsidence in part of a car park between two residential buildings. A hole opened in the ground revealing a stone arch and some walls. Experts believe the structure revealed is a Roman domus built maybe 2,000 year ago when the area just east of Stabiae would have been largely agricultural and dotted with country…