A couple of weeks ago I was lucky enough to take part in the scanning of a female mummy from ancient Egypt, and to take photos to document the experience. This young girl was only around 25 at the age of death, and survived in relative peace for thousands of years. In the last century, however, she’s been used as a bargaining tool by the Germans, survived attacks by torpedos and fires, and even suffered physical traumas. I discovered that the scientific analysis of a young mummy can show us a lot about the life in ancient Egypt, but tell us even more about her afterlife, in our custody.

A couple of weeks ago I was lucky enough to take part in the scanning of a female mummy from ancient Egypt, and to take photos to document the experience. This young girl was only around 25 at the age of death, and survived in relative peace for thousands of years. In the last century, however, she’s been used as a bargaining tool by the Germans, survived attacks by torpedos and fires, and even suffered physical traumas. I discovered that the scientific analysis of a young mummy can show us a lot about the life in ancient Egypt, but tell us even more about her afterlife, in our custody.

Swaps With Germany

The mummy in question was brought to Porto after some exchanging of merchandise between Portugal and Germany in the years following the First World War. The cargo of the ship Cheruskia consisted of pieces found by German excavations from 1903 to 1914 in Assur by Walter Andrae, an eminent German Assyriologist of the early 20th century. As part of an agreement made with Great Britain, Portugal imprisoned 70 German ships anchored at Portuguese ports in 1916. But Germany declared war on Portugal on March 9th. Cheruskia was seized at Lisbon by Portuguese authorities in April 1916, and, while interned at Lisbon, renamed Leixes. But the ship wasn’t safe yet – after the war, in 1918,it was torpedoed by the German submarine U-155 south of Newfoundland.

It stayed at Lisbons docks, in the Tagus river, for some years, and its cargo was sent to Portos Faculty of Letters to be identified and studied by a team of French Assyriologists. The valuable Assur artefacts were returned to Germany after they insisted on their repatriation. Some Egyptian Artefacts were given to Portugal as a gift in exchange. The documents read: ‘Offered to Portugal in 1926 by German authorities in exchange for the spoil brought from Assur by the Germans that was imprisoned by Porto University’.

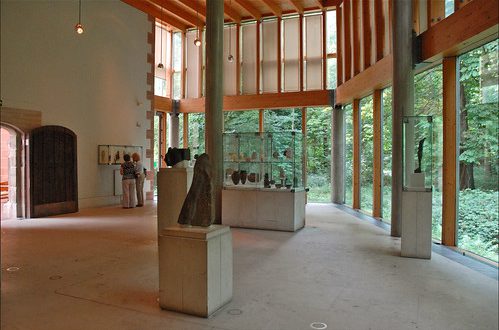

These Egyptian artefacts came as part of a mixed bag of ancient objects from Berlin’s collection. They went to Portos Faculty of Letters where they stayed until 1928, when they were passed on to the Faculty of Sciences. The collection was transferred to Museum Mendes Corra where it stayed from 1940 onwards. In 1996, the Natural History Museum of the Sciences in Porto integrated the Egyptian Collection displayed at the Mendes Corra Archaeology and Pre-History Room. This collection has been housed in the Faculty of Sciences Museum since 1996, but the Museum suffered a fire, and so the collection is now stored to be exhibited at what will be the new Mendes Correa Anthropology Museum in 2011.

The total of 102 pieces was listed in 1996, sponsored by Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, but nothing – catalogue or study report – was ever published. Two mummies came with this gift collection, and they are dated probably from the Late Period or Ptolemaic Period; a male mummy, completely wrapped (scanned and analyzed in November 2007 with some evaluation still in progress) and a female mummy, completely unwrapped – this is the mummy that I got the chance to see.

State of the Mummy

So how did our mummy fare throughout this?Well, remarkably well, in general, but one particular part of the mummy was showing excessive wear and tear – her teeth. This presented a dilemma – she appeared to have the constitution of a young adult, but the teeth of somebody at least ten years older.

Teeth are one of the most reliable sources of information regarding the determination of age-at-death, along with the pubic symphysis, the midline cartilaginous joint uniting the superior rami of the left and right illiacs. In this case doubt had arisen between the members of the team at the hospital, as the teeth showed extensive abrasive texture and couldn’t be indicative of the real age.

The abrasion in teeth of ancient Egyptians was caused primarily by their diet; bread and other food was prepared in open air and caught sand particles. This made chewing very hard and besides caries, periodontal disease and premature tooth loss, it also made many ancient Egyptians suffer from temporomandibular disfunction (this articulation connects the skull to the mandible allowing the mouth to open and close).

Infections like gengivitis and rotten teeth were common, but this one only missed a couple of teeth or so, so she was in pretty good shape for an ancient Egyptian.

The accuracy of these scans is very high and we can get proof of her exact real age from her teeth. In fact, all we need is one tooth – or even just a bit of a root. Scientists use a process called ‘dentin translucency’ to determine the age of the mummy from the teeth. This involves microscopic examination of the root’s dentin. A proposal to do this test was indicated by an odontologist present at the scanning. Let’s hope this project gets the funding to do all the tests needed…

The mummy also showed signs of stress marks on the atlas, and we discussed whether she might have carried weights on her head.

Evidence of Trauma

Our mummy did have evidence of trauma in the 5th and 6th cervical vertebrae, and three lumbar vertebrae show trauma resulting from the impact of different objects (one perforating object and another cutting one). These didn’t seem to have killed our sturdy young lady, and were probably inflicted after her death. Any of the following might have caused the injury:

- An apprentice mummification professional, not really sure where to pierce, maybe tryied to cut the kidneys out of the body

- Tomb robbers looking for jewellry in the thoracic/pelvic areas tryied to extract the amulets and gemstones, piercing the body and causing the damage seen on the vertebrae.

- The body was mishandled some way while still in Egypt, perhaps while changing sarcophagi, or moving from the tomb to the market/seller/warehouse

- The body was damaged in Germany while moving the mummy – she has no case and I believe she arrived in Portugal in a simple wood box; maybe the one she is still in.

This is an ongoing project but I know everyone is curious about Egyptian mummies’ mysteries and the paradoxes science unveils today with the help of new technologies. Looking at a single mummy in detail like this helps us to see that they are human and, like us, subject to trauma, accidents, disease, and aging. But they are all beautiful. At least to me.