New research by archaeologists at the University of York suggests that it is beyond reasonable doubt Neanderthals often misrepresented as furry, primitive caveman hobbling about had a deep seated sense of compassion.

New research by archaeologists at the University of York suggests that it is beyond reasonable doubt Neanderthals often misrepresented as furry, primitive caveman hobbling about had a deep seated sense of compassion.

Dr Penny Spikins, Andy Needham and Holly Rutherford from the universitys Department of Archaeology examined the archaeological record in search for evidence for compassionate acts in early humans. These illustrate the way emotions began to emerge in our ancestors six million years ago,which developed into the idea of ‘compassion’ we know today.

We have traditionally paid a lot of attention to how early humans thought about each other, but it may well be time to pay rather more attention to whether or not they ‘cared’, said Dr Spikins.

From Hominity to Humanity

Nowadays, ‘compassion’ which literally means ‘to suffer together’ is considered a great virtue by numerous philosophies and all the major religious traditions. But when did start to grow a desire to soother others’ distress? In the study ‘From hominity to humanity: Compassion from the earliest archaic to modern humans’, the researchers took on the unique challenge of charting key stages in the evolutionearly human’s emotional motivation to help others. They proposea four stage model for the development of human compassion:

Stage 1 – It begins six million years ago when the common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees experienced the first awakenings of an empathy for others and motivation to help them, perhaps with a gesture of comfort or moving a branch to allow them to pass.

Stage 2 – The second stage from 1.8 million years ago sees compassion in Homo erectus beginning to be regulated as an emotion integrated with rational thought. Care of sick individuals represented an extensive compassionate investment while the emergence of special treatment of the dead suggested grief at the loss of a loved one and a desire to soothe others feelings.

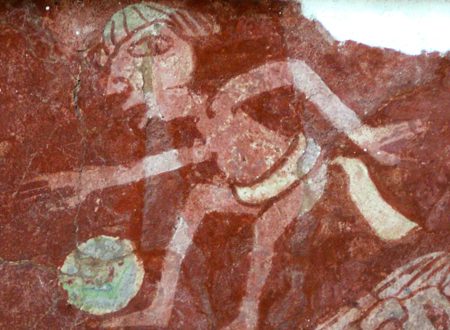

Stage 3 – In Europe between around 500,000 and 40,000 years ago, early humans such as Homo heidelbergensis and Neanderthals developed deep-seated commitments to the welfare of others illustrated by a long adolescence and a dependence on hunting together.

There is evidence of the routine care of the injured or infirm over extended periods. These include the remains of a child with a congenital brain abnormality who was not abandoned but lived until five or six years old millennia later, the Spartans would have acted differently. A Neanderthal with a withered arm, deformed feet and blindness in one eye must have been cared for, perhaps for as long as twenty years.

Stage 4 – In modern humans starting 120,000 years ago, compassion was extended to strangers, animals, objects and abstract concepts.

Dr Penny Spikins, lead author of the study, said that new research developments, such as neuro-imaging, have enabled archaeologists to attempt a scientific explanation of what were once intangible feelings of ancient humans and that the research was only the first step in a much needed prehistoric archaeology of compassion.

Compassion is perhaps the most fundamental human emotion. It binds us together and can inspire us but it is also fragile and elusive, said Dr Spikins.

This apparent fragility makes addressing the evidence for the development of compassion in our most ancient ancestors a unique challenge, yet the archaeological record has an important story to tell about the prehistory of compassion.

Dr Spikins will give a free lecture, ‘Neanderthals in love: What can archaeology tell us about the feelings of ancient humans’, about the research at the University of York on Tuesday 19 October.

‘From hominity to humanity: Compassion from the earliest archaic to modern humans’ by Dr Penny Spikins, Andy Needham and Holly Rutherford is published in the journal Time and Mind. The study is also available as a book, ‘The Prehistory of Compassion’, available for purchase online.