Using the latest techniques in forensic archaeology, the University of Reading has revealed a new image of multi-cultural Roman Britain. New research demonstrates that 4th century ADYork had individuals of North African descent moving in the highest social circles.

Using the latest techniques in forensic archaeology, the University of Reading has revealed a new image of multi-cultural Roman Britain. New research demonstrates that 4th century ADYork had individuals of North African descent moving in the highest social circles.

The research conducted by the University of Reading’s Department of Archaeology used modern forensic ancestry assessment and isotope (oxygen and strontium) analysis of Romano-British skeletal remains such as the Ivory Bangle Lady’, in conjunction with evidence from grave goods buried with her.

The ancestry assessment suggests a mixture of ‘black’ and ‘white’ ancestral traits, and the isotope signature indicates that she may have come from somewhere slightly warmer than the UK.

Taken together with the evidence of an unusual burial rite and grave goods, the evidence all points to the Ivory Bangle Lady’s high status in Roman York. It seems likely that she is of North African descent, and may have migrated to York from somewhere warmer, possibly the Mediterranean.

Dr Hella Eckardt, Senior Lecturer at the University of Reading, said: “Multi-cultural Britain is not just a phenomenon of more modern times. Analysis of the Ivory Bangle Lady’, and others like her, contradicts common popular assumptions about the makeup of Roman-British populations as well as the view that African immigrants in Roman Britain were of low status, male and likely to have been slaves.”

The research helps paint a picture of a Roman York – or Eboracum as it was known – that was hugely diverse and which included among its population, men, women and children of high status from Romanised North Africa and elsewhere in the Mediterranean.

Eboracum was both an imperial fortress (it was the last base of the famous Ninth Legion) and civilian settlement, and ultimately became the capital of Britannia Inferior. York was also visited by two Emperors, the North-African-born Emperor Septimius Severus, and later Constantius I (both of whom died in York). All these factors provide potential circumstances for immigration to York, and for the foundation of a multicultural and diverse community.

“To date, we have had to rely on evidence of such foreigners in Roman Britain from inscriptions. However, by analysing the facial features of the Ivory Bangle Lady and measuring her skull compared to reference populations, analysing the chemical signature of the food and drink she consumed, as well as evaluating the evidence from the burial site, we are now able to establish a clear profile of her ancestry and social status,” adds Dr Eckardt.

“To date, we have had to rely on evidence of such foreigners in Roman Britain from inscriptions. However, by analysing the facial features of the Ivory Bangle Lady and measuring her skull compared to reference populations, analysing the chemical signature of the food and drink she consumed, as well as evaluating the evidence from the burial site, we are now able to establish a clear profile of her ancestry and social status,” adds Dr Eckardt.

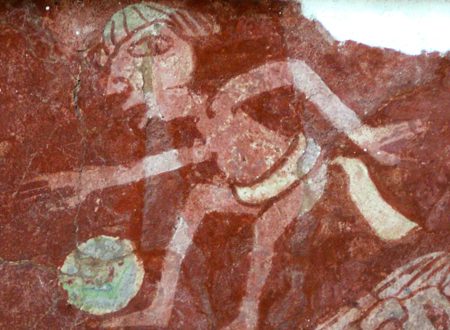

The Ivory Bangle Lady was a high status young woman who was buried in Sycamore Terrace, York. Dated to the second half of the fourth century, her grave contains jet and elephant ivory bracelets, earrings, pendants, beads, a blue glass jug and a glass mirror. The most famous object from this burial is a rectangular openwork mount of bone, possibly from an unrecorded wooden casket, which reads “Hail, sister, may you live in God”, signaling possible Christian beliefs.

The research was funded by the AHRCand conducted by the University of Reading’s Department of Archaeology, working with the Yorkshire Museum‘s collections. The museum will open in August 2010 following a major 2 million refurbishment. The skeleton and grave goods will be part of the museum’s exhibition entitled Roman York: Meet the People of the Empire, which aims to show Roman York in a new, cosmopolitan light, with inhabitants from Africa, Spain, France and every corner of the vast Roman Empire.