In 1972, the intact tomb of a noble lady of the Han dynasty was discovered at Mawangdui in the eastern outskirts of Changsha, China. Although eclipsed by the discovery of the life-sized terracotta warriors of Qin Shi Huang-di two years later, the Mawangdui tomb is still considered one of the most important archaeological discoveries of the 20th century and provided important insight into the lifestyle of the rich and famous of early Western Han society. The tomb was filled with food offerings and household items that Xin Zhui, the wife of the Chancellor or “Marquis” of the state of Changsha, a fief containing 700 households, would need to continue a luxurious lifestyle in the afterlife. Now, an exhibition in the Santa Barbara Museum of Art is blowing open one of the most scandalous eras – and one of the most ruthless women – of the Han empire.

Her astoundingly well-preserved corpse enabled researchers to conduct one of the most complete autopsies ever performed on an ancient corpse, revealing a startlingly human portrait of a lady of leisure:

“Plagued by a series of parasites and suffering from coronary thrombosis and arteriosclerosis, the obese noblewoman was further incapable of normal locomotion, the result of acute back pain initiated by a fused spinal disc (exposed via X-rays). Clogged arteries culminated in a profoundly damaged heart, ironically paralleling the contemporary health crisis of mass obesity fueled by economic plentitude, caloric overindulgence and lack of exercise. Gallstones further taxed Xin Zhui’s badly overburdened physiology; one of these abnormal masses of biliary calculus, according to expert medical consensus, lodged in her bile duct, aggravating an already precarious circulatory condition, and likely induced a colossal heart attack.” – The Last Feast of Lady Dai by Julie Rauer, Asianart.com

She had a fashionable wardrobe of some of the finest silk ever found still intact – one burial robe a delicate gossamer weighing only 49 grams.

Like most cultured ladies of the period she probably loved music, and her grave goods contained several musical instruments including a 25-stringed se and a 22-pipe yu. She was well groomed, evidenced by her lacquered cosmetic case with delicate combs, brushes and a bronze mirror. But, feasting and entertainments aside, what was life really like for a noblewoman in the Han imperial court?

Strong Women

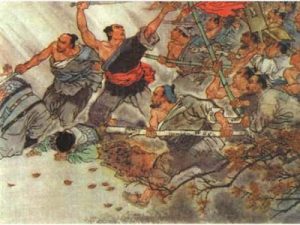

Virtuous, supportive wives were admired and held up as exemplars of behavior in ancient Chinese society, but women went far beyond the expected roles of marital relationships – leading rebellions, serving as political consultants, recording history, becoming revered teachers, commanding armies and even making or breaking the next emperor.

The impact of women’s contributions was never more evident than during the Han Dynasty – China’s Golden Age. Strong women were a a force to be reckoned with from the very beginning of the empire.

The first emperor, Liu Bang (Emperor Han Gaozu), was born a simple peasant, one of only two Chinese emperors (the other the founder of the Ming dynasty) from humble origins. As he and his followers battled the forces of the Qin, he encountered a vigorous female officer named Huang Guigu, who led Qin forces in northern China. “Lady Sima”, as she was officially called, studied military tactics at night, practiced military formations during the day, was strong enough to draw a stout bow and was revered for her talent at reading the stars. Recognizing her value, Liu Bang issued an imperial decree after his victory which gave Huang Guigu 300 catties of gold and jade to demonstrate his respect for her.

Although there is no record of Liu Bang commissioning Huang Guigu to command some of his own battalions, he actively recruited former Qin officials for positions in his new government. The burdens of administration of such a large empire must have seemed daunting. It is reported that he wrote the following poem at a wine party he gave in his

hometown after putting down an armed rebellion in 195 BC:

Song of the Great Wind

A great wind rises,

Clouds fly and scatter;

With power over the four seas,

I return to my homeland;

Where shall I get brave warriors

to safeguard the four qrarters?

(Tr.Ronald C. Miao)

Sleeping With the Enemy

Little did he realize at the time that his most formidable female adversary would end up being his own wife, the Empress Lü Zhi.

Lü Zhi was a daughter of a Qin magistrate for the county of Danfu. When Liu Bang was still but a roving rebel and visited Danfu, he was recognized by Lü Zhi’s father as a talented leader. Lü Wen predicted the young rebel would become a great man, so he granted Liu Bang the hand of his daughter in marriage. Lü Zhi bore the future emperor a daughter then, in 210 BC, a son. But, Lü Zhi spent the years during her husband’s conquest of the Qin empire in relative isolation with her father-in-law in Pei where her husband had grown up.

Finally, in 207 BC, the greatness foreseen by Lü Zhi’s father came to pass – the Qin dynasty fell and Liu Bang became the Prince (sometimes translated as “king”) of Han. However, he shared power with a brilliant but ruthless rebel general named Xiang Yu who, it is speculated, kept Lü Zhi, her children and her father-in-law as virtual hostages to derail any future of ambitions of his one-time rebel colleague.

In 205 BC, despite of the fact that his family were “under the protection” of Xiang Yu, Liu attacked his rival’s capital, Pengcheng, while the general was off campaigning against the nearby state of Qi. Xiang quickly withdrew from the Qi campaign and counter-attacked, nearly annihilating Liu’s forces and recapturing Pengcheng. In the aftermath, as Liu tried to retreat back to his own territory, he marched through Pei and tried to rescue his father, wife, and children. However, the young family became separated in the confusion. Although Liu rescued his children, his father and his wife were captured by Xiang’s forces and held thereafter as literal hostages, along with one of Liu’s officials, Shen Yiji. (Shen Yiji would became openly romantically involved with Lü Zhi after Liu Bang’s death).

General Xiang eventually released the trio under the terms of a truce with Liu Bang. But, with his family now safe, Liu broke the truce and decisively defeated Xiang Yu in 203 BC. Liu finally claimed the title of Emperor and named Lü Zhi as empress, designating their son, Liu Ying as crown prince, a seemingly happy ending.

But Liu still had to pacify other areas of the empire, so he spent years away from his family on campaign. While he was away, he put Empress Lü and the crown prince in charge of his new capital Chang’an and gave them the authority to make key decisions for the surrounding area, assisted by his long time supporter and new prime minister, Xiao He, and Zhang Liang, one of his military strategists.

Empress Lü proved to be an able administrator but soon her advisors saw that she had learned some hard lessons from Xiang Yu during her captivity.

In 196 BC, the emperor left the capital to put down a rebellion led by the Marquis of Yangxia. The new empress ordered the torture and execution of two former generals in her husband’s army based on rumors of their collusion in the rebellion.

Splitting Heirs

Now, it would appear that Empress Lü was acting to protect her husband’s position but could there have been more to it than just that? During this time, the emperor had become enamored with one of his concubines, Consort Qi, “The Benign”. Lady Qi bore him a son and, as the child grew older, the emperor thought the boy resembled him more than his firstborn with Empress Lü. Had the emperor began to wonder about an affair between his empress and his officer, Shen Yiji, imprisoned with her several years before?

In 199 BC the emperor appointed his new son to the rank of Prince of Zhao. Rumors began to spread through the palace that the emperor planned to replace the crown prince, who the emperor found to be weak and not at all like himself, with his new son, Prince Ruyi. So, could the Empress have been planning to appear to be actively protecting her husband’s interests while in fact diverting attention away from her own plans to usurp the throne?

The emperor summoned the crown prince and asked him to take command of a contingent of the army that was slated to engage enemy troops in a particularly hazardous battle. Empress Lü, fearing for her son’s safety prevented him from leaving for the battlefield. Instead, the emperor led the army himself and was gravely wounded. (The sources don’t mention “friendly fire” but the timing of the event raises suspicion).

When the emperor sucuumbed to his wounds and the crown prince was named Emperor Hui, Then Dowager Empress Lü imprisoned Lady Qi without her son’s knowledge and sent for the 12-year-old Prince Ruyi.

Now the young Emperor Hui felt kindly toward his half brother and feared that his mother might attempt an assassination of the young prince. So Emperor Hui intercepted his half-brother at Bashang then joined him on the trip to the palace where they kept each other company for several months. One morning, the emperor planned to go hunting but could not get his little brother to get up so early in the morning. Thinking the boy would be safe because he had now been at the palace for several months and no harm had come to him, the emperor left the palace. Upon hearing that her son was off hunting, the Empress summoned an assassin who forced the boy to drink a poisoned wine. The empress then ordered torturers to go to the prison where Lady Qi was kept and cut off her arms and legs, then deafen and blind her. The Lady Qi was then cast into a filthy pit.

Dangerous Empress Dowager Lü

When the emperor returned from his hunting trip, he learned that his brother was dead. His mother then took him to the prison and showed him a mud smeared mutilated creature that she called “Human Pig”. At first the emperor did not recognize Lady Qi but when it finally dawned on him who the poor unfortunate creature was, he was horrified. He subsequently withdrew from court affairs and spent the rest of his days drinking and womanizing.

He did rally one last time to defend yet another half-brother. In winter of 194 BC, Liu Fei, Prince of Qi, the emperor’s older brother by his father’s mistress Consort Cao, was invited to a feast hosted by Empress Dowager Lü. To honor his brother, the emperor invited him to sit in the most prestigious place at the table. The Empress Dowager was furious and sereptiously ordered her servants to pour a cup of poisoned wine for Prince Fei. As she toasted Prince Fei, the emperor, sensing his brother’s peril, snatched the goblet from him and brought it to his own lips. The Empress Dowager Lü then jumped up and slapped the cup away.

Although his half-brother had escaped death, poor Emperor Hui was still within his mother’s clutches, and she had succession plans for him. In 191 BC, the emperor was forced to marry the daughter of his sister. The marriage proved a childless one but it was alleged that the Empress dowager told her grandaughter, now empress, to adopt eight boys that were to be stolen from women that would be executed afterwards. Modern scholars speculate that these children were actually Emperor Hui’s by some of his concubines since killing the children’s fathers was not mentioned. One of these children became, only briefly, Emperor Qianshao, when his father died in 188 BC.

Four years after Qianshao became emperor, the young man somehow learned that his real mother was not his father’s empress but a woman executed by the empress. He became enraged and and was overhead when he swore revenge. Grand Empress Dowager Lü had the young emperor, probably her own grandson, locked up within the palace and put out reports that the emperor was ill and could not receive visitors. After a time, she claimed he was too ill to rule, had suffered a psychosis and should be deposed and replaced by his brother who would become Emperor Houshao. Grand Empress Dowager Lü then had the former emperor, probably in a drug-induced stupor by then, put quietly to death. Sadly, the young man’s brief reign coupled with allegations of psychosis resulted in his name being frequently omitted from the list of official Han Dynasty emperors, almost as if he had never even existed at all.

Grand Empress Dowager Lü continued her tyranny through her new puppet grandson, Emperor Houshao. She also immediately set about killing her late husband’s relatives and appointing members of her own clan as princes of Han.

But death finally claimed the scheming old woman in 180 BC. Grand Empress Dowager Lü was was returning to the capital after performing a temple sacrifice when “something that looked like a blue dog appeared and bit her in the armpit, then suddenly disappeared. Divination proved it to be the evil spirt of the King of Hao [Prince Ruyi’s] spirit. She grew ill of the wound in her side and shortly died. – Han Shu [History of the Han Dynasty] by Pan Ku, third century AD, (Tr. De Bary, 1960,172).

But her powerful clan still held the Han court in an iron grip. In fact, the wily old woman even attempted to rule from the grave. Her will stipulated that the new emperor would marry the daughter of the Grand Empress Dowager Lü’s nephew. But court officials, led by prime minister Chen Ping and commander in chief of the armed forces, Zhou Bo, rose up and slaughtered the entire Lü clan. Emperor Houshao was deposed, banished to the ministry of palace supplies building and later executed.

The Lady of the House

Lady Dai, buried in the tomb excavated at Mawangdui, lived during these dangerous and tumultous times. As a young woman, she must have been terrified as she witnessed the treacheries of the Han court and had to carefully guard her remarks around other noble ladies. Much is said of her apparent indulgence in food but maybe this was her escape from the emotional tension of her daily life.

Only in her thirties when her husband died, Lady Dai would have been a relatively defenseless widow with a young son at her side by the time the Grand Empress Dowager Lü finally died and the slaughter of the Lü clan began. Fortunately, her husband had been a general during the Qin uprising and subsequent conflict between the Chu and Han states, so he was not related to the Grand Empress Dowager. His wife and son, therefore, escaped the blood bath. Apparently, despite her relatively young age at the time of her husband’s death, she also did not remarry (which was allowed at this time) but lived out her years as a wealthy matron supervising her son’s household (the new Marquis of Dai – the title was inherited for four generations before a misstep resulted in its removal), a dowager of sorts in her own right although hopefully a much kinder, gentler one than Lü Zhi.

An exhibit of over 70 items from Lady Dai’s tomb, including lacquer ware, wood carvings, jade ornaments, bronze sculptures, seals, and silk costumes and textiles excavated are now on display at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art in Santa Barbara, California until December 13, 2009. The exhibit was organized by the China Institute Gallery in collaboration with the Hunan Provincial Museum, and is curated by Chen Jianming, Director of the Hunan Provincial Museum, who also edited the exhibit’s fully illustrated, bilingual catalogue. Although many of the objects are original, the beautifully embellished and lacquered set of nested coffins displayed is a replica. The originals were deemed too fragile for travel and rermain, along with Lady Dai’s corpse, in the permanent collection of the Hunan Provincial Museum.