At its peak during the 2nd century AD, Roman London (Londinium) had a population of up to 60,000 people and represented a thriving urban centre. But as the Roman Empire declined over the next 300 years, so too did the city. In 410, Britain was cut loose from the Empire altogether, and with it London. Troops and officials departed, and the city was left to fend for itself.

At its peak during the 2nd century AD, Roman London (Londinium) had a population of up to 60,000 people and represented a thriving urban centre. But as the Roman Empire declined over the next 300 years, so too did the city. In 410, Britain was cut loose from the Empire altogether, and with it London. Troops and officials departed, and the city was left to fend for itself.

Exactly what happened during the immediately ensuing phase in London’s history – which is referred to as the Sub-Roman period, and lasted from approximately 450 until 600 AD – is mysterious. A small enclave of wealthy families is believed to have continued to inhabit villas to the southeast of the Roman city into the 5th century. But by the end of the 5th century, they – along with almost everyone else – had left. London was abandoned.

Situated on a broad and deep river, surrounded by flat terrain and bountiful wetlands, the city’s strategic location remained undeniable, and it wasn’t long before a new phase in London’s history began, as the Anglo-Saxons became the dominant force in post-Roman Britain. They ushered in a new and turbulent era in the future British capital’s history, one that would last over 600 years, until the Norman Conquest in 1066, and turns it prove prosperous and violent, as the city prospered as a trading hub but struggled to resist the bloodthirsty attentions of Viking raiders.

Who Were the Anglo-Saxons?

All kinds of foreign invaders sought to fill the power vacuum left by the retreating Romans – Picts and the Scots threatened from the north and west, while Germanic tribes encroached from the south. In 449 AD, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle – our key source of information on the Anglo-Saxon era, compiled in the 9th century from the writings of early historians such as Gildas and the Venerable Bede – the Britonic warlord Vortigern is said to have invited Germanic mercenaries to help defend his lands.

Must-know Facts About Anglo-Saxon London:

- 410 – Romans leave Britain and London

- C. 550 – Anglo-Saxons have become the dominant force in post-Roman England, and begin building their own city on the Thames, Lundenwic

- 842 – The “great slaughter”, London sacked for the first time by Viking raiders

- 865-871 – The Great Heathen Army invades England and captures London

- 878 – King Alfred the Great defeats the Danes at the Battle of Ethandun, and retakes London

- 886-896 – Old Roman Londinium re-settled and reinforced by Anglo-Saxons

- 1013-1014 – Danes lay siege to and eventually capture London, causing Æthelred the Unready to flee to Normandy

- 1014-1016 – Æthelred returns and recaptures London, pulling down London Bridge in the process, but the Danes hit back and become rulers of England

- 1066 – Edward the Confessor dies childless, sparking a chain of events that leads to the Norman Conquest and the end of Anglo-Saxon rule

These mercenaries revolted, however, and soon drove the Britons out, before establishing themselves as the dominant regional power. It’s not certain whether the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is true, but the story does provide some telling clues as to how and why Germanic peoples in the fifth and sixth centuries came to settle and take control over just one area among many in the south and east of what would become known as England.

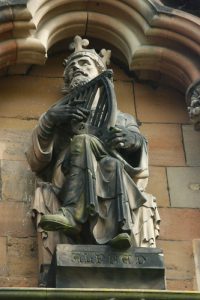

These invading tribes included the Saxons, Franks and Frisians of German-Dutch extraction, the Southern-Danish Angles and the Northern-Danish Jutes. Their rapid immigration was driven by a shortage of good farmland in their native territories. Eventually, all of these tribes would blur together into one people whose name emerges in records during the time of King Alfred the Great, who reigned from 871 to 899. He frequently used the title “rex Anglorum Saxonum” – which basically means “king of the English Saxons”. The language spoken by the Anglo-Saxons was called Englisc, and the lands they inhabited became known as England.

Under the Anglo-Saxons, England became divided into a dense and complex array of petty kingdoms, all of which jostled for power and status over the centuries. For a long time scholars believed there were seven main polities, known as the Heptarchy – Northumbria, Merica, Kent, East Anglia, Essex, Sussex and Wessex. However, this idea has fallen out of favour, since there appears to in fact have been many more petty kingdoms scattered across the country in this era, including Hwicce, Magonsaete, Kingdom of Lindsey and Middle Anglia, to name but a few.

The London area technically fell within the boundaries of the East Saxons, although its importance wasn’t lost on the kings of other territories, including the rulers of Kent, Mercia and Wessex, who each took the city into their direct control at different stages. Under the shifting influence of these power blocs, a brand new city was established on the Thames, and quickly prospered.

Lundenwic: “A Market for Many Peoples Coming by Land and Sea”

The Anglo-Saxons didn’t move into the Roman remains, but instead established their own city – Lundenwic – one mile (1.6 kilometres) west and upriver of Londinium (which came to be known as Lundenburh or “London Fort”). Lundenwic began life as a small trading-settlement as early as mid-6th century, in roughly the same spot where the Strand and Charing Cross exist today. By the early 9th century it had expanded into a city of approximately 600,000 square metres, with boundaries roughly equivalent to those of London’s modern West End.

The wealth and relative sophistication of Lundenwic isn’t to be underestimated. Excavations by archaeologists during the renovation of the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden in the 1990s found evidence to suggest the city was very well-organised. It has to be, as a major industrial trading hub (“wic” was an Anglo-Saxon word for “trading town”, so Lundenwic literally meant “London trading town”) with a large harbour that connected it directly with other major English and continental towns and cities.

The wealth and relative sophistication of Lundenwic isn’t to be underestimated. Excavations by archaeologists during the renovation of the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden in the 1990s found evidence to suggest the city was very well-organised. It has to be, as a major industrial trading hub (“wic” was an Anglo-Saxon word for “trading town”, so Lundenwic literally meant “London trading town”) with a large harbour that connected it directly with other major English and continental towns and cities.

A grid system of well maintained roads – resurfaced at least ten times in 200 years – were unearthed. Artefacts found in the ruins included pottery and millstones originating from France and Germany – proof of extensive foreign trade. Coinage was minted in the city for the first time since the departure of the Romans, and a cash economy – which also seems to have made use of Roman money as a peripheral, low-value currency – appears to have operated. Excavations of an Anglo-Saxon cemetery in 2008 revealed some of the city’s residents to haven been relatively wealthy individuals of middle to high class, who were able to afford jewellery and other luxury goods, as well as expensive funerals.

Bede wrote in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle of Lundenwic being “a market for many peoples coming by land and sea.” At its peak in the late 8th century, the city’s population may have been as high as 10,000 people. Clearly, this was a large, well-to-do and cosmopolitan place by the standards of the time. Sadly, this meant it didn’t go unnoticed by outsiders, and the peace was soon shattered under the hammer of murderous raiders from the north.

“The Great Slaughter”

Viking incursions into the British Isles began with raids against monasteries in Scotland and the north of England in the late 8th century. By the early part of the 9th century, Scandinavian pirates – attacking directly from Denmark, Sweden and Norway – had started to venture further and further south in search of blood and treasure. They soon began to wreak havoc on Lundenwic, which at that time was effectively an open and undefended site (remains of a system of log ramparts, palisades and ditches dating from the period have been discovered along one side of the city by archaeologists, but these defenses evidently proved little protection).

The first Viking assault on London – referred to by one chronicler as the “great slaughter” – occurred in 842. Houses were burned, men killed and women raped. Not satisfied with their orgy of terror, the Vikings returned to inflict further suffering on Lundenwic in 851 in a raid that is said to have involved as many as 350 ships. By then, the city was close to deserted, its inhabitants scattered to the countryside in fear.

A full-scale Viking invasion of England was launched in 865, as The Great Heathen Army – a Danish force thousands strong, one of the greatest Viking armies ever assembled – landed in East Anglia, having already terrorised the continent. Led by Halfdan Ragnarsson – a ruler so cruel even his own troops hated him – and Ivar the Boneless, a warrior known as a “berserker” for his habit of descending into a trance-like fury in battle, the force successively conquered three of the four main kingdoms of England at that time – Northumberland, East Anglia and Merica – leaving a trail of misery and destruction in its wake.

The whole of England was in danger of falling. By 871 the Viking horde was on the outskirts of Lundenwic, and may even have occupied the city altogether. They didn’t stay for long, though – one of the most famous kings in Anglo-Saxon history made sure of that.

Alfred the Great

In 1871 King Alfred became ruler of the southern kingdom of Wessex – the only Anglo-Saxon kingdom to at that time remain independent from the invading Danes. We know lots about Alfred, because the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle was created during his reign. Indeed, the Chronicle was probably composed on his orders, in a bid to revive learning and encourage the use of English as a written language, not to mention record for posterity the undoubted achievements of the only British monarch to attain the suffix “the Great”.

In 1871 King Alfred became ruler of the southern kingdom of Wessex – the only Anglo-Saxon kingdom to at that time remain independent from the invading Danes. We know lots about Alfred, because the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle was created during his reign. Indeed, the Chronicle was probably composed on his orders, in a bid to revive learning and encourage the use of English as a written language, not to mention record for posterity the undoubted achievements of the only British monarch to attain the suffix “the Great”.

Born in born in 849 at Wantage, Oxfordshire he was the youngest son of King Æthelwulf of Wessex. His love of learning was legendary – one popular story about the young Alfred (probably not true, but revealing at least as to the mythology history has built around him) has it that he won a volume of poetry as a prize from his mother, by becoming the first of her five children to memorise the book in its entirety.

After assisting his brother King Aethelred in beating back the Danes at the Battle of Ashdown in 870, Alfred ascended to the throne (his father had insisted that his sons become king in turn, so that none of them would be forced to rule at a young age) just as the tide of war turned back against the Anglo-Saxons.

Over the next few years, the Danes attacked into Wessex again and again, inflicting defeat after defeat on Alfred’s embattled kingdom, at one stage nearly capturing the king in his winter fortress at Chippenham. He tried to fend them off, if not by military might then with treaties and bribes, but by 878 Alfred was forced to retreat to the marshes of the Somerset Levels and mount a guerilla campaign from Fort Athelney. The Anglo-Saxon reign in England was at its lowest ebb, but still clinging on.

The Battle of Ethandun

A decisive encounter occurred in the spring of 878 at the Battle of Ethandun (or Edington). Emerging from his swamp hideout, Alfred rallied the remaining militia forces of Somerset, Hampshire and Wiltshire at Egbert’s Stone, east of Selwood, who “rejoiced to see him” according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles. His remarkable success in raising an army seemingly from nowhere was testament to his skill in maintaining the loyalty of a network of officials responsible for levying and leading forces, and also his cunning deployment of scouts and messengers.

King Alfred and his army marched to Ethandun (the exact position of which remains unidentified, but is thought to be near modern Westbury in Wiltshire) and on an unknown date between May 6 and 12, clashed with The Great Heathen Army. The Anglo-Saxons were outnumbered, but their tactics were shrewd. Using a technique that must have been passed-down in military learning from the Roman occupation, they locked-shields, “forming a dense shield-wall,” according to the Chronicle.

“Fighting ferociously… and striving long and bravely… at last he [Alfred] gained the victory. He overthrew the Pagans with great slaughter, and smiting the fugitives, he pursued them as far as the fortress.”

“Fighting ferociously… and striving long and bravely… at last he [Alfred] gained the victory. He overthrew the Pagans with great slaughter, and smiting the fugitives, he pursued them as far as the fortress.”

The fortress mentioned ironically enough was Chippenham – where Alfred had narrowly evaded capture the previous winter. The Anglo-Saxons laid siege to the stronghold, forcing the Danes to the brink of starvation. King Guthrum, the Danish leader, was forced to sue for peace. Alfred was wise enough to accept that he didn’t have the strength to eject the Danes from Britain altogether, so he allowed them to hold onto and preside over a territory known as the Danelaw, comprising the Kingdom of Northumbria, the Kingdom of East Anglia, and the lands of the Five Boroughs of Leicester, Nottingham, Derby, Stamford and Lincoln. Another – presumably quite humiliating – condition of the surrender was the Guthrum had convert to Christianity, with Alfred as his sponsor.

With the Vikings defeated, Lundenwic was returned to Anglo-Saxon control. It would become a key stronghold of a newly fortified Anglo-Saxon kingdom, which was now unified under one monarch.

The Revival of Roman London

A period of relative stability and expansion returned to London after the defeat of The Great Heathen Army. Across Anglo-Saxon England, following the devastation of the Danish invasion, Alfred set about turning various important cities into fortified strongholds called “Burhs”. London was one such city.

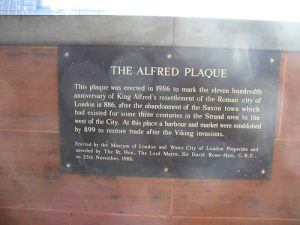

It’s a testimony to Roman engineering that the Anglo-Saxons chose to strengthen the city’s security by retreating to Londinium, the great walls of which still stood firm. By 896, settlement in Roman London was reestablished, and what would centuries later become the modern City of London had effectively been founded. It’s defenses were reinforced with a freshly-cut ditch surrounding the walls, and London Bridge – the old Roman version of which was probably destroyed during the Viking invasion – was rebuilt. On the southern side of the Thames, a new borough was founded called Southwark. Lundenwic, meanwhile, was left practically deserted, and became referred to as Ealdwic or “old settlement,” the etymology of which still survives today in the area of Aldwych.

Alfred handed control London to his son-in-law Ealdorman Aethelred of Mercia in 886; upon Aethelred’s death in 911, London for the first time came under the direct rule of the English kings. The capital of England remained at Winchester, but London became an important political centre for the Anglo-Saxons.

That prominence was mirrored in its burgeoning fortunes. Commerce blossomed once more, and wealth flowed. Modern institutions began to form. Portreeves were appointed – precursors of the county sheriff, responsible for collecting taxes – and the Peace Guild was established, a kind of very early antecedent of the Metropolitan Police, charged with the “repression of theft, the tracing of stolen cattle, and the indemnification of persons robbed,” according to the Anglo-Saxon dictionary.

But there was more turmoil to come, as the Danes – with whom a fragile peace had barely held for long – returned to take the jewel in the English crown for a second time.

King Æthelred the Unready and the Second Danish Conquest

King Æthelred II is another Anglo-Saxon king whose name is remembered with a suffix, albeit a much less generous one than the Alfred’s – “the Unready”. Strictly speaking it was actually “The Unread” – a play on his name, meaning “without good advice” (Æthelred’s counsel was notoriously poor) – but over the centuries the meaning has become twisted.

King Æthelred II is another Anglo-Saxon king whose name is remembered with a suffix, albeit a much less generous one than the Alfred’s – “the Unready”. Strictly speaking it was actually “The Unread” – a play on his name, meaning “without good advice” (Æthelred’s counsel was notoriously poor) – but over the centuries the meaning has become twisted.

His reign is remembered as being weak – Æthelred failed to encourage loyalty in his men, and believed he could buy off the growing threat of the Danes with tributes. He paid mercenaries to defend English lands when he could have better invested the money in building a strong army. Sensing this weakness, Vikings began raiding into Anglo-Saxon lands again in the 980s, led by King Sweyn Forkbeard of Denmark. In 1014 Æthelred was forced to flee England for Normandy.

The first Danish attack on London came in 994. It was unsuccessful, but many more raids followed, culminating in a long siege from 1013-1014 (it was this that prompted Æthelred, who favoured the city as his capital, to take flight). The city was isolated, in a country that was now completely controlled by the Danes. But Æthelred returned in the spring of 1014, backed by his ally King Olaf of Norway, and together they drove their common enemy out of England.

A Norse saga from the period tells a famous tale of Æthelred’s recapture of London. The English and Norwegian forces attacked on boats up the Thames, so the Danes lined London Bridge to pelt them with spears and other missiles as they approached. Æthelred’s army defended itself by stripping the roofs of houses to use as shields. They were able to get close enough to the bridge to attach lines to its piers, then row so powerfully away from the fragile structure that it came crashing down into the river. The nursery rhyme London Bridge Is Falling Down is said to originate from this incident.

The triumph was short-lived. By the time of Æthelred’s death in 1016, much of England had been re-conquered by King Sweyn Forkbeard’s successor Cnut (or Canute), who recommenced attacks on London. Æthelred’s son Edmund Ironside led a valiant resistance against the Danes, but was finally defeated at the Battle of Ashingdon in Essex on October 18, 1016. He was forced to cede all territories north of the Thames to the Danish king, including London.

The Norman Conquest and the End of Anglo-Saxon London

After Edmund Ironside’s death in November 1016 (apparently of natural causes, although some legends have it that he was assassinated) King Cnut (or Canute) became ruler of all of England, as well as Denmark and Norway. He ruled very well – since most Viking raiders were under his control, he was able to cease violence against London and England, and allow the resumption of trade and prosperity. But he also made the mistake of devolving a lot of power to noblemen or “earls” (which originates from the Danish word “jarl”), setting in motion a chain of events that would herald the end of the Anglo-Saxon period in England, and usher in a new dawn for the country.

After Cnut’s death, and the short reigns of two further Danish kings – Harold Harefoot and Harthacanute – the Anglo-Saxon line was restored when Æthelred the Unready’s son by Emma of Normandy, Edward the Confessor, took the throne in 1042. Edward would prove the last effective Anglo-Saxon King of England.

After Cnut’s death, and the short reigns of two further Danish kings – Harold Harefoot and Harthacanute – the Anglo-Saxon line was restored when Æthelred the Unready’s son by Emma of Normandy, Edward the Confessor, took the throne in 1042. Edward would prove the last effective Anglo-Saxon King of England.

He too allowed English nobles, such as Earl Godwin of Wessex, to increase in strength. When Edward died, childless, in 1066, no heir was apparent. The late king’s cousin, Duke William of Normandy, claimed the throne but the Witenagemot – essentially the English Royal Council – met in London and choose Godwin’s son and Edward’s brother-in-law Harold Godwinson as the next king. William was incensed, and immediately launched an invasion that culminated in the Battle of Hastings, Harold’s death and the Norman Conquest of England.

London was never actually defeated by William – after his victory at Hastings, he marched on the city and captured Southwark, but was prevented from crossing London Bridge. The city later surrendered, and William rewarded Londoners by granting them a special charter in 1075, allowing London a unique degree of autonomy within Norman England, paving the way for its growth into an economic and political powerhouse. With the carrot came the stick, though, and he also built a number of castles near the city to keep it subdued, among them the Tower of London.

With Anglo-Saxon rule over, a wholesale cultural and political transformation began, based on systems and ideas imported from the continent. London was on its way towards becoming the modern capital of the unified England and Britain it represents today.