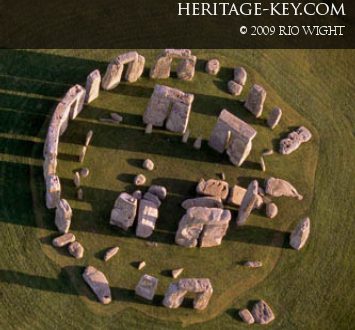

The Riverside Project is the largest archaeological investigation ever carried out at Stonehenge. Its basic hypothesis is simple: that Stonehenge was a monument to the deceased, while the nearby Woodhenge and other timber circles in its vicinity were monuments to those still alive. The River Avon was the sacred connection between the two, “a kind of Styx,” comments Mike Parker Pearson, a professor in the Department of Archaeology at Sheffield University and director of the Riverside Project. “It was a river linking the living and the dead.”

The success of the initiative – which first broke ground in 2003 and will return for another season of fieldwork at the site this August and September – has amazed even the most optimistic of team-members and observers. Not only has their hypothesis held firm (a rare thing for any archaeological investigation) but many new and remarkable lines of inquiry have been launched and some fascinating and unexpected discoveries made – discoveries that have forced a re-evaluation of hitherto sacred beliefs about the monument.

The success of the initiative – which first broke ground in 2003 and will return for another season of fieldwork at the site this August and September – has amazed even the most optimistic of team-members and observers. Not only has their hypothesis held firm (a rare thing for any archaeological investigation) but many new and remarkable lines of inquiry have been launched and some fascinating and unexpected discoveries made – discoveries that have forced a re-evaluation of hitherto sacred beliefs about the monument.

“Although people think the Stonehenge World Heritage site has been very fully researched, and we know everything there is to know, we’ve really just exposed the levels of our ignorance,” Parker Pearson remarks. He gave Heritage Key an insight into the Riverside Project’s findings to date, and a few clues as to what lies ahead in the search for answers to some of archaeology’s biggest questions.

Beginnings

The first shovelful of soil being dug up and cast aside is the symbolic starting point of any archaeological dig, but it tends to obscure the sheer amount of preparatory work that needs to be done beforehand. Stonehenge is a world-famous site with a particular degree of emotional and historical resonance, so the Riverside Project – a collaboration between five UK universities – had an especially long and complex build up process to negotiate.

“In reality the project began as early as 1998,” explains Parker Pearson, “That was when the original hypothesis to go out and explore and see if some of the predictions that we’d made would hold water. 2002 was the point at which I realised that no one else was going to go ahead and check out our model. So I realised I was going to have to go out and do it myself.”

He spoke to various colleagues, developed a team and began the delicate process of negotiations – with landowners, the National Trust, English Heritage and various other organisations – necessary to obtain permission and funding. “We just started off with a few very small grants. We applied for a big grant, but it was turned down because our project was deemed too speculative.” What the Riverside Project needed was a big discovery. They were about to get one – but it would be bigger than they could have dreamed.

Hitting the Archaeological Jackpot

Durrington Walls is located two miles north east of Stonehenge, in the parish of Durrington, by Woodhenge. Its Neolithic significance had been hinted at but never fully proven, until 2003, when in their first season of fieldwork the Riverside Project located what would turn out to be the remains of an extensive settlement. In the 3rd century BC it had housed perhaps thousands of people – most likely the same ones that built Stonehenge during that phase.

“Up until that moment I think if somebody had said to me ‘you’ll find well-preserved house-floors in the Wessex chalk lands,’ I would have laughed out loud,” says Parker Pearson, “because the chalk lands are very unforgiving to ephemeral remains like that – one ploughing and they’re completely destroyed. We just happened to chance upon one area that was perfectly undisturbed – it hadn’t been ploughed in pre-history or in more recent times.”

One of the main tenets of the Riverside Project’s hypothesis had been proven – namely that a sizeable site of life and living once existed upstream from Stonehenge. Additionally, the remains turned out to have fascinating parallels with buildings, dating from the same period, located hundreds of miles north at Skara Brae in Orkney, Scotland. “Finding all the houses I think was a really major landmark,” Parker Pearson continues, “it was the point at which we could say: ‘look, we’ve really found something, and it’s not just any old thing – it’s really extraordinary.’”

The project was rolled out and enlarged to the point where during digs, as many as 160 people might be on the ground at any given time, with scores more providing support behind the scenes.

More Discoveries

More Discoveries

The physical link between Durrington Walls and Stonehenge was discovered in 2005 in the form of the Avenue, a three kilometre processional causeway between Stonehenge and the River Avon, which flows past Durrington Walls. Their good fortune was slightly less spectacular this time, however. “We put the trench in the wrong place in 2004, and missed it,” Parker Pearson explains, with a laugh. “Then we found it the year after.”

Stonehenge’s role as a monument to the dead was proven with the discovery of multiple sets of human remains, 60 so far in total, most of them in the Aubrey Holes. Many of these bones had actually been dug up before in the 1920s, but then replaced, because they weren’t considered to be of great significance. “Unfortunately they’re all mixed together, but we’ll eventually be able to single out the different individuals, look at them, get radiocarbon dates, and get a trajectory of mortality through the history of Stonehenge. We already know that they were buried throughout the monument’s use from the 3rd millennium, 3000 BC, to about 2300 BC.”

Advanced results of research on the bones suggests that all of the deceased were male, almost all of them adults, and most likely all of them pretty important. Further research on their remains, as well as on the bones of animals found in the area, will give an idea as to how far and wide Stonehenge’s power extended. “We’ll be able to work out where these people were living before they ended up at Stonehenge,” the professor adds. “That’s going to be very interesting to understanding the catchment area – where people were coming from to help build Stonehenge and take part in the ceremonies.”

What Next?

All kinds of additional finds have been made by the Riverside Project that, while not strictly core to their goals, are welcome bonuses nonetheless. “Not only have we characterised and dated a lot of sites within the world heritage site that simply weren’t dated, we’ve found new ones, that nobody had any idea were there,” says Parker Pearson. “Important ones, like the stone dressing area right outside of Stonehenge where they shaped the sarsens before they put them up. That’s a massive site. It had not even been thought of until we found it last summer.”

The next season of fieldwork will concentrate on the site of a whole other henge altogether, found at the point where the Avenue meets the River Avon. It may be the hub of the connection between Stonehenge and Durrington Walls. “We’ve been speculating from the start that that stretch of the River Avon is very important – it has to be the central point around which everything else revolved. We excavated at the end of the Avenue, because we wanted to see where the Avenue met the river. Last year to our surprise we found another henge. That points to the interface with the river being very important. Se we’re going to wait and see what we find.”

After that, the focus will be on lab work, and extracting and analysing every last bit of data picked up during fieldwork. They’d love to go out and start digging up other sites of interest, such as a spot in Avesbury 20 miles north of Stonehenge which they believe may have been the source of the monument’s huge sarsen stones. Yet Parker Pearson stresses that the team can’t get carried away with themselves. “What we’ve located is a possible quarry source. There’s a field project just waiting to be started, but obviously it’s a case of finishing what we’re on now – getting all of the scientific reports written and all of the detailed results out in the public domain before we kick off on a new project.”

Towards a New Paradigm

Towards a New Paradigm

Even if the Riverside Project is able to renew its funding and continue its research for a long time to come, professor Parker Pearson is resigned to the fact that answers to certain questions will never be established. “One thing everybody wants to know is how they got the sarsens to Stonehenge,” he says. “That’s a question we’re never going to be able to answer, unless we have video footage of them lashing the stones to cradles and dragging them along. And we’re never going to know who all these men were who were buried at Stonehenge.”

In a general sense though at least, he sees the Riverside Project as helping to push Stonehenge research into a new, third phase. “We’ve been through two paradigmatic possibilities so far,” he explains. “The first was that Stonehenge is a sun temple – that idea stretches back 300 years. The next was from the 1960s, as the world entered the space age, when people became convinced that it was an astronomical observatory – that’s still a very strong hypothesis in a lot of peoples’ minds. I think we’re moving on now to looking at how astronomy was harnessed for social goals at the time.”

What does he mean by that? “Rather than seeing Stonehenge in the old hypothesis of being an astronomical observatory,” Parker Pearson explains, “it’s now just one of a number of monuments – wood and stone – from that period around 2500 BC when the architecture is all about the feasting, the gatherings that took place at that time of year. So it’s applied astronomy.”

They Came From… Manitoba

There are many more outlandish theories about Stonehenge out there too of course, and Parker Pearson knows all about them. He gets, as he puts it, “bombarded” with emails from amateur theoreticians every time one of the Riverside Project’s new discoveries makes the news.

“There are all sorts of weird and wonderful possibilities that people think of,” he says. “A lot of them of course don’t work, because they may not have the depth of archaeological knowledge. Some of them are really charming; some of them potentially have possibilities. I think it’s interesting to see how Stonehenge really works on peoples’ imaginations.”

And no matter how wild they might be, the Riverside Project chief reckons it’s always healthy for people to get their Stonehenge theories out there into the open. “The more people debate them the better,” he insists, “even if it’s a farmer from Manitoba telling me that Stonehenge is built to repair the undercarriage of an alien spacecraft damaged in an alien star war.”

“I think that’s the great think about any subject we study,” Professor Parker Pearson adds, “whether it’s astronomy or archaeology. People are fascinated because it’s something that takes us out of our everyday boring lives and shows us other worlds, other possibilities of how people might have lived. That’s what’s really exciting.”