Heritage Key was recently introduced to Dr Ray Howell – a reader of history and historical archaeology at University of Wales, Newport and Director of South Wales Centre for Historical and Interdisciplinary Research (SWCHIR) – through the short film Reclaiming King Arthur.

Heritage Key was recently introduced to Dr Ray Howell – a reader of history and historical archaeology at University of Wales, Newport and Director of South Wales Centre for Historical and Interdisciplinary Research (SWCHIR) – through the short film Reclaiming King Arthur.

Filmed in association with University of Wales’ Institute of Digital Learning (IDL), it examined the Gwent roots of the legendary British monarch of round table fame – both the real figure, who may have been a 5th or 6th century local warlord, and the mythical Arthur championed in countless folk tales.

Dr Howell’s latest area of research is the Silures, a warlike tribe of south Wales who put up a fierce resistance to the Roman invasion of Britain, yet remain an obscure bunch in the grand scheme of British history. His acclaimed book on the topic – Searching for the Silures, an Iron Age tribe in South-east Wales – first published in 2006, is set for a reprint in 2010. Dr Howell has also been assisting in an effort by the IDL to create Second Life virtual reconstructions of Welsh heritage sites, including the Newport Ship and Newport Castle.

In a wide-ranging chat with Heritage Key, he discusses academically sound methods of harnessing the legend of King Arthur as a tourist attraction in Gwent, the latest on his Silures research, and the possible Welsh origins of Stonehenge.

HK: Explain a little of the background of Reclaiming King Arthur, and the context in which it was made?

RH: For several years there’s been a growing school of thought that it would sensible in and around Caerleon to make more of the tourist potential of Arthur. But that raises all sorts of its own problems, simply because – as the film suggests – the historical Arthur is a very shadowy concept. The video was a direct response to the question that’s been going around Caerleon for the last couple of years: should more be made of this Arthurian connection, and if so, how are we going to do it? The video is just an attempt to say “well, look, here’s a way to do it.”

The point I was trying to make is that there are at least two – or depending on how you want to define them, umpteen – King Arthurs. There’s the historical Arthur in the sense of the 5th or 6th century warlord, assuming there was such a person, and there probably was. But we’re on much safer ground when we look at the later sort of embodiment of Arthur, the legend of Arthur. That’s got very good Gwent roots, and Caerleon roots.

HK: What is that attracts you to studying King Arthur?

RH: Let me be perfectly candid – my main interest is less Arthur focused and more early medieval focused. What I try to stress to students is: this period that so many people call the Dark Ages, for a whole variety of reasons we’re not going to call it that. It’s not a dark age in the sense that we can’t get at it through historical evidence, nor was it a dark age in terms of decline of literacy and a decline of society, particularly in western Britain. You do have disruption and cultural change, religious change and all sorts of things in the east. But in the west that doesn’t happen so much, so it’s that early medieval period I’m quite interested in.

HK: So you’re comfortable with the legend of King Arthur being used for tourist reasons then, as long as people have an understanding of its wider historical context within the early Medieval period?

RH: Sure, and legend in history is important. You can see cases where legend, and what people call the historical myth, is really more important in terms of shaping what happens in history than anything else. So yeah, it’s a perfectly legitimate sort of area upon which to pick up.

One of the things I’m looking at now is things like landscape change. I’ve got a feeling that there’s quite a lot of tribal continuity when we come to that early Medieval period – you know, when we start getting into that Arthurian zone, I think there’s still a lot of tribal tradition left in this part of the world. So that’s something else I’ve been working on, and will continue to work on for the next six months or so.

HK: Are new media learning tools something you’re eager to look into using further?

RH: Yes, it’s something that we’re really eager to try to get into. I think it’s really great. Reclaiming King Arthur was a co-production by two research centres, mine SWCHIR – which sounds like it should be a good Welsh word, but it isn’t (laughs) – and IDL. The idea is really sort of pushing the parameters of digital media. We’re really keen on combining the two things, and applying digital technology to history.

One of the things we’re looking at now is Second Life. We’ve got an island and we’re picking up important historical themes for that island. One of the things we’re working on is the Newport Ship – this big late medieval ship that was dug up in Newport a few years ago. It’s out of the ground now, it’s in tanks on an industrial estate, and at some stage the hope is to be able to put it back together, like the Mary Rose. But we don’t have the funds to do that at the moment, so what we are trying to do is put it back together in Second Life. I think that’s really cracking.

Newport Castle is in a bit of state right now, and we want to do a reconstruction of the castle and let that castle become a sort of virtual museum, so the avatar can go into the castle museum and hit on various bits of media that talk about the history of the area. I think that’s cracking too, because quite apart from anything else, that’s the way to go to reach a younger target group. (To try exploring a virtual heritage site, check out Heritage Key’s King Tut Virtual).

HK: When can we expect to see these Second Life reconstructions up online?

RH: Well, it’s fairly early days yet, but we’ve been working with the local council and a group called the Friends of Newport Ship, and it’s coming together. We’ve got a ship and a castle – we’re just tweaking them to make them a much more accurate ship and castle. We’re getting there.

HK: Your current area of research is the Silures – introduce them for us.

RH: Basically, they were the major Iron Age tribe in South East Wales – Gwent Glamorgan. They caused the Romans huge problems – a 25 year guerilla war. In recent years, because of things like the Portable Antiquities Scheme, we’re getting a better idea of their material culture – a little bit of hill fort excavation, the most recent of which we actually did. We did the work on Lodge Hill, which is a big hill fort overlooking Caerleon – that’s the site that featured in the film.

The material culture is showing us all sorts of interesting things. To give you just one example, we’re finding lots of things like lynchpins and territs. Now, the only thing I know you can do with a territ is lead reigns through it, and the lynchpin holds a wheel on an axle, so what we’re seeing clearly is that they were using wheeled vehicles – war chariots I suspect.

Something else that’s interesting – the harness fittings and all that stuff, it’s remarkable the extent to which the decoration of it all of it is covered in red enamel. It’s almost all red, so I’ve suggested that for the Silurians, red may have been the colour of war.

They were quite an enigmatic people. There’s this ferocious resistance, and all sorts of cultural distinctiveness, and yet they haven’t attracted the sort of archaeological and historical evidence that I think they merit. That’s really the sort of reason I’ve taken them on as a subject. What I tried to do in the book is: a) draw all the evidence that we have to date together and say “look, here’s what we know about them,” and b) to also suggest that there’s ways that we could find out more about them.

HK: Is your book, Searching for the Silures, one of the first comprehensive studies of the tribe?

RH: It probably is, yes. And I must admit I sort of felt that when I did it, it would end up being a one-off. But having done it, I don’t think it is. What I’m looking at now is landscape patterns, which might turn out to be another book. I’m looking at hill forts and line of sight between them. I don’t think you can find a hill fort in this part of the world from which you can’t see at least one other hill fort. And they also seem to be clustered, which might be evidence of clans and a clan structure.

We’re playing with some mapping packages and just trying to see what that tells us. Where it could really become interesting is, when I get that Iron Age landscape sorted out, I want to drop the Romano-British landscape on top of it, then the early medieval landscape on top of that, and just see if there’s any sort of continuity. Even if it doesn’t tell us much, there’s a sense in which it is telling us something.

HK: Which sites would you recommend visiting to people who have an interest in learning more about the history of the Silures?

RH: The most obvious things are the hill fort sites. A good visit is Llanmelin, which is near Caerwent, the Roman town. It’s a cracking site.

We’re in Caerleon which was the legionary fortress. The army was here, and we’ve got some good Roman ruins here. About ten miles down the road there was Caerwent, which was the Roman town.

It was also what was known as the “capital of the Silures”. At some stage – probably Hadrianic – the Romans devolved some responsibility for local administration back on the tribe, and the capital from which that was done was Caerwent. There’s some amazing still-standing Roman walls – some of the best in Britain. There’s an excavated basilica forum complex for example.

About exactly a mile north of Caerwent, on the hill above it, is the Llanmelin hillfort, which is one of the Silurian hill forts. So it’s dead easy if people fancy a day trip – do the Roman town and then do the hill fort. And you can very much the same thing with Caerleon and Lodge Hill – a town and then the hill fort up above. The two things can easily be done in one day, so I’d recommend doing them both.

HK: In a much more general sense, do you think that ancient Welsh history has perhaps become unfairly marginalized and obscured in the grander scheme of ancient British history?

RH: I think that’s probably true. It’s much less true within Wales itself, recently. But once you got from Wales itself, it probably is the case. In terms of widening awareness, it’s Wales we want to start with, and certainly that’s improving. I’ve done a lot with undergraduates, and I’ve got a number of PhD students who have concentrated on Welsh related subjects. I think our understanding of early Welsh history is improving, but I imagine that what you get outside of Wales is probably pretty shadowy.

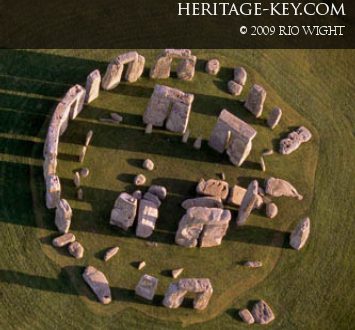

HK: What are your thoughts on the theory that Stonehenge was built by the Welsh?

RH: It’s an interesting theory, and you do have the bluestones that clearly came from west Wales – I don’t hear any question about that. How they got there is something that people will argue about at great length. But at the very least there’s that Welsh connection, and there could be more.

One of the things that people find so difficult with studies in prehistory – and even aspects of the early medieval period – is that so often, the answer to the question is “we don’t know.” You’ve got to get your head round that, and accept that there’s a hell of a lot we don’t know. We’re dealing in balance of probabilities at best – I don’t mind that, I find that quite interesting. But some people find that difficult.

I do know that we’re beginning to understand Stonehenge itself a lot better than we did previously. There have been recent excavations by Mike Parker Pearson, and a colleague of mine was involved as well – Josh Pollard. I wouldn’t hazard an opinion until I’d talked to them. But I do want to find out what they discovered this summer.

HK: Are there any other ancient sites in Britain that perhaps have hidden Welsh origins?

RH: One of the first things you have to do in these early periods is ask: how are we defining Welsh? Linguistically there were parts of Britain which were basically Welsh speaking for a very long time – the old north of England and southern Scotland for example. You just have to look at some of the place names to think “crikey, there are obvious language links here.”

Then there’s the early Welsh language poem Y Gododdin – which describes something that happened in the old north, and actually has an interesting Arthurian reference in it. It’s one of these marshal epics, and at one stage this poet is describing a war leader and extolling this chap’s virtue.

Now that is interesting, because the gutting of black ravens – obviously he’s killed a lot of people, which the poet sees as a good thing. The way it translates, he’s saying basically “he gutted black ravens on the wall of the fort – but it wasn’t Arthur.”

What the poet’s telling us is: this chap was good at what he did, he was a war leader and he was good at killing people – but he wasn’t Arthur, mind. It’s a throwaway line, because the poet is clearly assuming that everybody knows who Arthur is. That’s a very early Welsh language poem, and it’s set in the old north. So there are all sorts of things that you can play with if you want to go down that line.

HK: Can we expect to see you in any more films soon?

RH: Well, I don’t know. I quite like that sort of thing, but the stuff I was doing this summer to camera, I was just doing because I’m cheap! We might – I’d love to do something on the Silures.

HK: But you’re not angling going to become the new David Starkey or Simon Schama?

RH: No no! I do the odd bit of television – I did a Time Team recently, that was interesting. But I don’t have a wide audience outside of Wales. It’s still very much a sideline – I’m not aiming for a new career!