It was announced last week that the hotly disputed Lewis Chessmen are to be reunited for the first time in 150 years, when a number of the bulk of pieces held by the British Museum in London arrive for a tour of Scotland, the country where they were discovered, throughout 2010 and 2011. They aren’t the only historical artefacts of Scottish origin that the Scots stake a fierce claim to, or have had to fight to get back.

It was announced last week that the hotly disputed Lewis Chessmen are to be reunited for the first time in 150 years, when a number of the bulk of pieces held by the British Museum in London arrive for a tour of Scotland, the country where they were discovered, throughout 2010 and 2011. They aren’t the only historical artefacts of Scottish origin that the Scots stake a fierce claim to, or have had to fight to get back.

Calls for repatriation have been made over all from the Safe Conduct letter – written by the King of France and taken from William Wallace when he was captured by the English in 1305 – to the remains of Mary Queen of Scots (currently buried at Westminster Abbey) and the remarkable Cladh Hallan Mummies. Most of the items are or were held by the Scots’ next-door neighbours the English, a nation with whom the Scots have shared a close, fraught and frequently violent history over the centuries. Others artefacts are in further-flung countries, including France and Germany.

1. Lewis Chessmen

The National Museum of Scotland owns 11 of these 93 beautifully hand-carved ivory chess pieces, found on the Isle of Lewis in 1831. The other 82 are kept by the British Museum in London, which bought them from a Scottish merchant not long after their discovery. Calls by the Scottish ruling part, the SNP, for the Chessmen’s repatriation has seen them become a national political issue. They’ll finally return to Scotland next year, but only in the short term.

2. The Cladh Hallan Mummies

These remarkable mummified Bronze Age bodies were found in 2001 – by an archaeological team from Sheffield University, led by Mike Parker Pearson – buried under the floor of a prehistoric house at Cladh Hallan on the Hebridean Island of South Uist. Dating from around 3,200 years ago, they predate Tutankhamun, and represent the first proof that ancient Britons made mummies of their kings and queens just like the Egyptians did. Yet, since being quietly whisked away to a research laboratory in Sheffield, they haven’t been seen in Scotland again since. Under provisions of the Treasure Trove Act they should be granted to a Scottish museum.

3. Chronicle of the Kings of Alba

A short chronicle with a long history, this unique document – a list of Scotland’s first royal family, the 12 kings of the House of Alpin – is 1,000 years old, and has been described as the “birth certificate of Scotland,” since it contains the first ever mention of Albanium – a Latinised version of the Gaelic name for Scotland. Since the 17th century, it’s been in the hands of the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris, the national library of France. A campaign for the Chronicles of the Kings of Alba’s repatriation was launched by Scottish politicians and historians in 2008.

4. The Safe Conduct

This letter, known as the Safe Conduct, was written by King Philip IV of France, and intended to ensure safe passage for legendary Scottish revolutionary William Wallace (of Braveheart fame) while on his way to visit the Pope. It was taken from Wallace when he was captured (then later hung, drawn and quartered) by the English, at Robroyston near Glasgow in 1305. Currently the letter is held in the British National Archives in Surrey; earlier this year, a Member of the Scottish Parliament, Christine Grahame, lodged a motion calling for its return north.

5. Stone of Scone

Better known as the Stone of Destiny, this 153-kilo hunk of red sandstone – used since at least the 9th century AD during the coronation of Scottish, English and British monarchs – was taken from Scone near Perth in 1296 by Edward I, and kept at Westminster for six centuries. It was famously stolen by Scottish students in 1950 and returned north, before being recovered and taken back to London. In 1996, the stone was officially repatriated (it sits at Edinburgh Castle today), but the English reserve the right to reclaim it for future coronation ceremonies.

6. The Cutty Sark

The grand old merchant clipper the Cutty Sark – the last ever clipper ship constructed for use as a merchant vessel – was built and launched at Dumbarton on the River Clyde in 1869. Since 1954 she’s sat in a custom-built dry-dock in Greenwich London, and has since been converted into a popular museum ship. Scottish voices have called for the ship to be returned to her home port. They have a good case, but the Cutty Sark is not going anywhere anytime soon: gutted by a fire in 2007, she’s presently undergoing major restoration work.

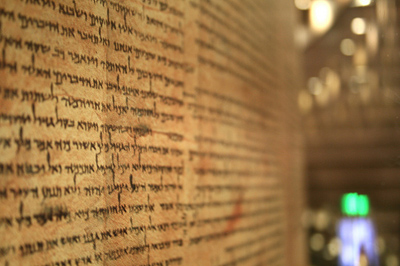

7. The Book of Deer

This 10th century Latin Gospel Book from Old Deer in Aberdeenshire contains perhaps the earliest surviving Gaelic literature from Scotland, and may also be the oldest surviving manuscript produced in Scotland. At present, it’s held in the library of the University of Cambridge. There has been a long-term campaign for its return to Scotland.

8. Mary Queen of Scots

The remains of Mary I – the romantic and tragic Queen of Scots, who was imprisoned and eventually had her head chopped off at the order of Queen Elizabeth I – are currently interred at Westminster Abbey in London. In 2008, Christine Grahame – the same MSP who requested the return of the Safe Conduct letter – presented a motion to the Scottish parliament demanding repatriation of Mary’s body, and its re-burial at Falkland Palace in Fife, a popular Stuart retreat.

9. Hilton of Cadboll Stone

This magnificent carved Pictish stone, discovered at Hilton of Cadboll in Easter Ross, Scotland, was taken from a nearby chapel to Invergordon Castle in the 19th century, then later donated to the British Museum, provoking a public outcry. It was eventually returned to the National Museum of Scotland however, where it remains today. A missing lower portion of the stone was found by archaeologists in 2001, and put on display at Hilton of Cadboll village hall.

10. The Lübeck Letter

The second of two items in this list pertaining to Scotland’s legendary freedom fighter William Wallace is the only surviving document issued by Wallace himself. The Lübeck Letter was sent to merchants in Lübeck and Hamburg, Germany, in 1297, informing them that Scottish ports were once again open for trade, in the wake of Scots victory over the English at the Battle of Stirling Bridge. It now resides in the City of Lübeck’s National Archives. In 2009, MSP Murdo Fraser raised a parliamentary motion for the permanent return of the document to Scotland.