With Bettany Hughes’ documentary ‘Atlantis: The Evidence’ set to première on BBC Two, what better way to prepare than to explore the Aegean Bronze Age treasures of the British Museum? If the Minoan civilisation was indeed home to the Atlantis legend, what better way to get to know the Atlanteans than through what they left behind? And, lets face it, visiting London’s most famous museum is far easier than getting a permit to dig beneath the sphinx. 😉

Though not that many items excavated by Arthur Evans can be found at the British Museum – I probably should have visited the Ashmolean for that, or Knossos? – they still have an amazing collection of Cycladic, Minoan and Mycenaean artefacts. This is my top 10 from Room 12a ‘The Minoans’.

01. Minoan Bull Leaper

Bull-leaping is frequently depicted in Minoan art on murals as well as statues, leading scholars to believe it was an important part of ritual activity. Although the difficult and dangerous leaps shown are not always possible, it is likely the bulls were restrained or even tamed. Depictions of bulls being captured, tethered and led have been found. The frequent depictions make it probable Minoans were skilled in the sport, but the likelihood that jumps were presented with some artistic freedom should be kept in mind.

The acrobat is supported upon the sculpture by his hair trailing unto the bull’s forehead, as well as the jumper’s feet. His arms end in stumps: it is not clear if this was intentional or if it was a casting fault. Due to a lack of tin in Minoan bronze, the alloy did not flow well. This is also responsible for the statue’s bubbly surface.

The Minoan Bull Leaper – part of ‘A History of the World in 100 Objects’ – is dated to 1700 to 1450BC, and thought to be from Crete. It is the British Museum’s most famous Minoan treasure, but there are many more worth mentioning.

02. Spedos Figure of a Woman from Syros

A quick jump back in time brings us to this female figurine, dated between 2700 and 2400 BC and said to be from Syros. Syros was part of the Cycladic civilization and early Bronze Age Aegean culture, dating from 3000 to 2000BC.

The Cycladic period is best known for the flat female figures carved from the islands’ pure white marble hundreds of years before, to the south, the Minoan culture was born.

What is so special about this figurine (besides that it is totally gorgeous) is that it is not made from marble – perhaps because it was produced on one of the few islands where marble is not found – but from compacted volcanic ash, most likely from the island of Thera.

Sadly the figurines were much wanted, and many of the statues are without provenance or their discovery sites looted. This lack of context means we’ll most likely never find out their exact meaning. Regardless of this they are absolutely stunning, and would not be out of place if given a home in Tate Modern.

By the end of the Cycladic period, Cycladic and Minoan civilisations converged, bringing me back to my Top 10.

03. Minoan Tablet inscribed with Linear B

This clay tablet inscribed with the Linear B script was discovered at Knossos by Sir Arthur Evans, and is dated between 1450 and 1375 BC. It records quantities of oil offered to various deities.

From the three scripts that survive from Minoan Crete, Linear B is the only one deciphered.

Linear B was used to write an early form of Greek, whereas the other two – hieroglyphic and Linear A – presumably represented the native Cretan language.

All of the tablets recovered so far (more can be found at the Ashmolean) describe how resources were managed at the Minoan palace. No historical, literary or even religious texts have been recovered, which leads scholars to believe writing had a very limited application in the Greek Bronze Age.

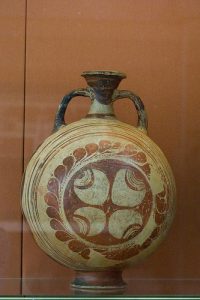

04. Minoan Pottery

The British Museum has an impressive collection of Minoan pottery. I admit I’m not much of a pottery fan, but there are Minoan tea cups (well… they look like tea cups) that would look just as at home at Buckingham Palace and the palace of Knossos.

But the most beautiful piece must be this vase.

It was found at Maroni (Cyprus) and is dated between 1400 and 1350 BC. It has a lovely wheel-shaped motive, covered with leaf patterns, and its colours match the whole ‘autumn’ idea (or that was how I interpreted it) quite well.

The vase created by throwing two bowl-shaped halves separately and then joining them together, after which the neck and handles were added.

05. Gold Plaques (Aigina Treasure)

The Aigina Treasure is named after the island on which it was found, but seems largely to be of Minoan Cretan workmanship, made perhaps between 1850 and 1550 BC.

It may have belonged to the member of a Minoan family (or families) living on the island, and could have been buried with them.

These 54 gold plaques (sorry I didn’t manage to capture them all in one photograph) were made to form an almost identical series. Each of the rosettes is pierced to be sewn onto fabric, and they probably decorated a dress or shroud.

06. Large Gold Earring with Cute Little Owls (Aigina Treasure)

The workmanship of the Aigina Treasure shows a high degree of skill and sophistication. Perhaps this points to an origin for some of the jewellery on Crete itself, or perhaps it was produced on Aigina by an immigrant Cretan craftsman.

The workmanship of the Aigina Treasure shows a high degree of skill and sophistication. Perhaps this points to an origin for some of the jewellery on Crete itself, or perhaps it was produced on Aigina by an immigrant Cretan craftsman.

Large earrings are often shown in Minoan art, but the two pairs of large gold Aigina Treasure earrings are the largest and most elaborate examples discovered so far.

Within a hoop formed by a two-headed snake are hounds and monkeys, while pendant discs and (terribly cute) owls hang from the hoop.

Whoever wore them must have gone for the ‘dramatic’ effect rather that usability.

07. ‘Master of Animals’ Pendant (Aigina Treasure)

Most of the semi-precious stones used in the Aigina Treasure jewellery occur in the Aegean area, but amethyst probably came from Egypt, and lapis lazuli was imported from Afghanistan via a long trade route.

Minoan stylistic elements dominate the treasure, but foreign influences can be seen: the nature god on this pendant, although Minoan in dress, stands among Egyptian lotus flowers.

The male figure on this pendant wears a Minoan kilt, a tall head-dress, bracelets and earrings. He strikes the pose of the ‘Master of Animals’, in which a central figure flanked by animals demonstrates control over them. The curved and rigged elements surrounding the birds derive from stylised bull’s horns.

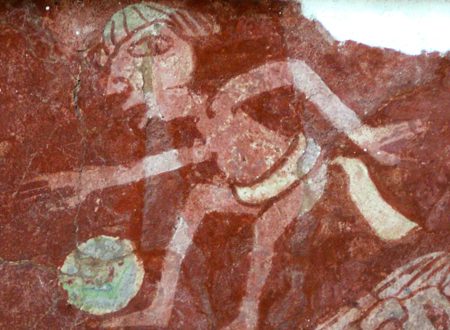

08. Minoan Terracotta Coffin or Larnax

Minoan burials were placed in tombs, and were frequently made in coffins – either shaped like bathtubs (also on display at the British Museum) or chests.

The coffins were often elaborately painted with scenes that seem specifically chosen for their funerary significance. Sometimes the burial was accompanied by rich grave offerings.

09. Petrie’s Silver Pendant from Egypt

This unique silver piece of jewellery, dated to about 1800-1700BC, was acquired by Flinders Petrie in Egypt and is on loan from the Petrie Museum. The closest parallel is a golden pendant discovered at Tell el-Daba (Avaris), showing two confronted dogs. This ‘Avaris pendant’ has been identified as Minoan, partly on the basis of its comparison with the ‘Master of Animals’ pendant from the Aigina treasure.

The animals on the silver pendant are falcon-headed winged griffins wearing symmetrical c-spiral head-dresses. Both of them stand on stylised papyrus boats similar to the Avaris and Aigina pendants. Technically all three are alike, with an upper plate of sheet metal worked in relief backed by a plain sheet.

The relationship of these three pendants requires further study, and maybe more can be discovered about them, but they certainly seems to connect Pharaonic Egypt and Minoan Crete.

Another artefact on display that makes one ponder this connection is an Egyptian Late Middle Kingdom (about 1800BC) glazed steatite scarab with gold inlay and inscription in an unknown script. This unusually fine scarab seems to be of Egyptian workmanship, but the script is not. Two of the signs on the scarab are also found in Linear A (though it needs to be said, other scripts certainly existed in the eastern Mediterranean at this time.) The inscription on the scarab remains a mystery.

10. Bronze Bull

Let’s end this Top 10 how it started, with a Minoan bronze bull. Yet I somehow fear this animal figurine (found on Crete and dated to 1300-1200BC) will never leap from the shadow of his larger counterpart.

If you liked this Top 10, there’s way more on display at the British Museum, from the Minoan, Cycladic and Mycenaean cultures that are worth checking out, but often ignored in favour of their more ‘Spartan‘ or ‘democratic‘ follow-ups.

The documentary ‘Atlantis: The Evidence’ with historian Bettany Hughes airs this Wednesday – 2nd of June 2010 – on BBC Two. Are you convinced the Minoans inspired Plato’s account of Atlantis? Let us know! And guess what? As the Minoan – and later Mycenaean – civilisations exchanged goods and ideas with Egyptians, maybe those pyramidiots putting Atlantis’ secrets under the sphinx aren’t that far off? 😉