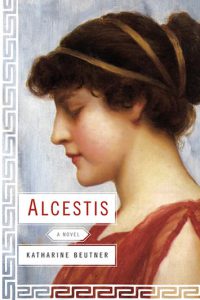

by Katharine Beutner

by Katharine Beutner

Katharine Beutner puts a new twist on the ancient Greek myth of Alcestis, the wife so devoted to her husband she agreed to die for him. In the myth, Apollo persuaded the Fates to allow King Admetus of Pherae to live past the time of his appointed death if someone else would agree to die in his place. When not even the king’s elderly parents would do so, his wife, Alcestis, offered herself. She spent three days in Hades before her mourning husband sent Heracles to the underworld, where he won a wrestling match with Death and was allowed to return Alcestis to the world of the living.

In the Greek conception of the cosmos, Hades was the gloomy and forbidding place where the vast majority of the dead persisted as shades. The dead Achilles is said to have reported that he would rather be a slave among the living than a king in Hades. Beutner describes the vagueness of the dead with eloquent precision. They sway “drunkenly” and whisper “in grass-dry voices.” Alcestis reaches to touch one “and felt a tickle like goose down beneath my fingertips. Eddies of shade spun off of her, tendrils of self dissipating into nothing, and I jerked my hand back, resisting the urge to wipe my fingers on my shift.”

Freud famously mined the Greek myths, a treasure trove of psychological insight, when developing his theory of the Oedipus complex. He might just as easily have named his theory of the death instinct after Alcestis.

Death and Yearning

Anyone versed in psychology might wonder whether a wife agreeing to die in her husband’s place is truly the sign of a happy, healthy marriage. In Beutner’s novel, Alcestis finds more sadness and uncertainty in her marriage than joy. From the beginning, the closeness of the relationship between Admetus and Apollo foreshadows trouble. “There were words in the air unspoken, like the lines of text painted around the borders of murals, writing I didn’t know how to read. Apollo stared back at my husband, and his face reflected like polished bronze: longing and fear, longing and fear.”

But the true roots of Alcestis’s choice lie in her childhood. When her mother dies giving birth to her, death becomes Alcestis’s first and closest companion. In later years, the mother’s attendants recall “the way the girl had opened her tiny mouth to suck in the fouled air as if it could replace her mother’s milk. Perhaps she’d grown used to death then, they’d say. Perhaps she’d been hungry for it all her life.” After a beloved sister dies, Alcestis often slips away to visit her grave, thinking, “if I . . . looked down long enough, perhaps the earth would open and swallow me, pull me down to the underworld like a sea nymph pulling a pretty sailor over the side of a ship.”

Alcestis as Heroine

In the ancient Greek world, royal women lived in seclusion, their lives defined by the choices of their fathers and husbands. “A royal girl must lie like an undiscovered island, quiet and empty, skin clear and pure as miles of open shore just waiting for that first footprint, the rut of the hull in the sand, the press of discovery.” And though Alcestis occasionally voices a protest, her cry of “I did nothing!” rings true. Until she volunteers for death, she is essentially a passive heroine, acted upon rather than acting.

It is in Hades, surrounded by the shades of the dead, where she seems to come truly alive. She searches actively for her sister. She dares to challenge Persephone, the Queen of the Underworld. Persephone has a presence and self-assurance missing in earthly queens, who would never casually command their husbands, “Be silent.” When, after Persephone questions her, Alcestis looks to the god Hades before answering, the goddess responds sharply. “Look at me,” she tells Alcestis. “It is I who ask, not he.” Here, in the upside-down atmosphere of Hades, Alcestis first experiences a passion resembling that of her husband for Apollo.

Alcestis is the most richly imagined character in the novel, with Persephone a close second. Admetus arrives on the scene with an assertiveness and clarity of purpose that vanishes after he marries Alcestis, making one wonder how he worked up the gumption to pursue her so intently and why he wanted to. But Alcestis carries the tale, along with the gods and goddesses who are her real adversaries and foils. This is a beautiful, mourning dream of a novel that, like Alcestis, comes alive when it enters the realm of death.