As the Director of the Stonehenge Riverside Project, Mike Parker-Pearson recently found himself at the centre of one of the decade’s most exciting and significant discoveries – Bluestonehenge (or Bluehenge in early reports). But this new ‘mini Stonehenge’ is part of a much broader understanding of the area being built up by the Stonehenge Riverside Project as they try to put together a history of the area rather than focusing on individual monuments in isolation. In an illuminating lecture at Wiltshire Heritage Museum, Parker-Pearson revealed some surprising theories about the construction and meaning of the henges.

As the Director of the Stonehenge Riverside Project, Mike Parker-Pearson recently found himself at the centre of one of the decade’s most exciting and significant discoveries – Bluestonehenge (or Bluehenge in early reports). But this new ‘mini Stonehenge’ is part of a much broader understanding of the area being built up by the Stonehenge Riverside Project as they try to put together a history of the area rather than focusing on individual monuments in isolation. In an illuminating lecture at Wiltshire Heritage Museum, Parker-Pearson revealed some surprising theories about the construction and meaning of the henges.

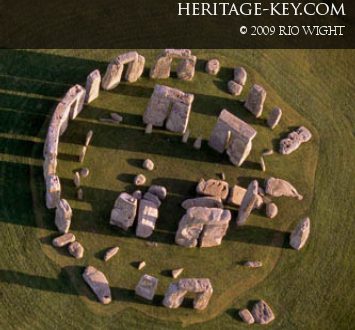

The Stonehenge Riverside Project is investigating the development of the Stonehenge landscape in Neolithic and Bronze Age Britain, and has already uncovered the site of Durrington Walls. The excavations are being carried out by 55 archaeologists from Sheffield, Manchester, Bournemouth, Bristol, Preston and Birmingham Universities under the directorship of Mike Parker-Pearson, from Sheffield University. This lecture was held at the Wiltshire Heritage Museum, Library and Gallery, for the Wiltshire Archaeological & Natural History Society (WANHS), founded in Devizes in 1853.

The focus of the excavations in 2008 and 2009 was on locating the ends of the Avenue leading away from Stonehenge. The edge closest to Stonehenge has been identified on the far side of the A344 next to the heel-stone, in the form of two parallel ditches approximately 20-22 metres wide. When this area was excavated two environmental archaeologists on the team pointed out that these ditches were in fact natural gullies dating back to the ice-age. These natural features were in perfect alignment with the solstice which were then utilised by the builders of Stonehenge as the location of the Avenue.

It was whilst Parker-Pearson and his team were excavating near the River Avon to locate the other end of the Avenue that they stuck archaeological gold in the form of the new Bluestonehenge. Initially they discovered the end of the Avenue, which at this point was narrower than the end at Stonehenge, measuring only 18 metres across. The Avenue itself is not a straight path running from Stonehenge to Bluestonehenge – it has a dogleg bend in it. Parker-Pearson attributes this to the topography of the area, believing that the construction of the Avenue was guided by the contours of the land.

It was whilst Parker-Pearson and his team were excavating near the River Avon to locate the other end of the Avenue that they stuck archaeological gold in the form of the new Bluestonehenge. Initially they discovered the end of the Avenue, which at this point was narrower than the end at Stonehenge, measuring only 18 metres across. The Avenue itself is not a straight path running from Stonehenge to Bluestonehenge – it has a dogleg bend in it. Parker-Pearson attributes this to the topography of the area, believing that the construction of the Avenue was guided by the contours of the land.

Further along the Avenue, by the river, there are a series of post-holes indicating that this part at least was lined with wooden posts, although at the Stonehenge end these post-holes are absent. A radar survey carried out by the Dutch firm GT Frontline on the land beside the River Avon showed the circular outline of the ‘new’ henge. Initially it was obscured by the Medieval earthworks, which created a lot of background on the scan. With hindsight, the henge was clear to see.

Excavation work over the last two seasons has uncovered half of the henge; archaeologists believe that the southern edge has been corroded by the river. The henge is constructed in a similar manner to Stonehenge, albeit on a much smaller scale, with a ditch surrounding it and a series of pits in the centre, placed in a circle. These pits were slightly different shapes and sizes, indicating that the stones were erected in stages, by different teams, rather than as a single project planned and exucuted by the same group of people.

The pits have proved to be quite interesting, as not only have they displayed the imprints of heavy stones, which weighed up to four tons each, but also depressions showing how they were dragged from the pits when they were removed as the henge fell into disuse. At the base of each pit a socket was created using flint picked up from the river banks, used to place the large stones into. These stones have been identified as bluestones based on chips of the stone found in the pits and surrounding ditch. These chips suggest that the bluestones were in fact shaped at the site before they were erected and the chips of stone were detritus from this process.

Through examination of the fill in the pits, the archaeological team are trying to date when Bluestonehenge was dismantled. However, it appears the answer to this question could lie at Stonehenge itself. When examining the final stage of building at Stonehenge, in the horseshoe of bluestones in the centre of Stonehenge, stone 68 is shaped like a kidney bean at the base, which matches the imprint of one of the pits at Bluestonehenge almost perfectly. Although further examination is necessary, it looks as if Bluestonehenge was dismantled and stones redeployed in the final building stage of Stonehenge. Rudimentary dating so far indicates this was approximately 2200 BCE.

The bluestones from Bluestonehenge, as at Stonehenge, originate in Wales, at the quarry at Carn Goedog which shows the closest match to the stone type. These stones, weighing four tons each, were transported over 240 miles to the site of the henges. It is often stated that transportation was via river wherever possible although Parker-Pearson has his doubts. He believes these stones were used for a ritualistic purpose, and that having them dragged across the land by hundreds of men would connote a higher status than if they had taken the easy route by water.

The bluestones from Bluestonehenge, as at Stonehenge, originate in Wales, at the quarry at Carn Goedog which shows the closest match to the stone type. These stones, weighing four tons each, were transported over 240 miles to the site of the henges. It is often stated that transportation was via river wherever possible although Parker-Pearson has his doubts. He believes these stones were used for a ritualistic purpose, and that having them dragged across the land by hundreds of men would connote a higher status than if they had taken the easy route by water.

He also believes that the Welsh connection is important and possibly the key to interpreting the purpose of Stonehenge and the surrounding area. Stonehenge and by default Bluestonehenge seem undoubtedly connected with ancestor worship, and the discovery of over 60 cremation burials at Stonehenge, and large amounts of charcoal at Bluestonehenge, indicating it could be the cremation site itself, supports this.

The cremations at Stonehenge were in fact a part of the structure of the standing stones, as a number of the Aubrey holes were packed with cremated bones, holding the standing bluestones in place. Being part of the structure itself may have been an important element of the henge complex, and Parker-Pearson believes the people who built Stonehenge may have been of Welsh origin, who may have colonised the area. Constructing the henges with the bluestone was perhaps a means of honouring their Welsh ancestors.

Parker-Pearson drew a parallel to the henge at Llandygai near Bangor, which is of similar size to Bluestonehenge but follows the structural design of Stonehenge, and shows further links between Salisbury Plain and Wales. In order to prove this theory Parker-Pearson needs to identify the origins of the people buried at Stonehenge. Fortunately, teeth have been discovered from the cremations which can be used for this purpose. A further pit burial at Coneybury comprises the remains of a ritual feast of eight cows, a number of pigs, roe, deer, and beaver, and he is hoping the study of these teeth and bones may show Welsh origins for the fauna as well.

The work at Bluestonehenge and the wider context of the Salisbury Plain is only in its infancy for Parker-Pearson and his team as there is still a great deal left to discover. In the near future the main aims of the archaeological team is to take the faunal, floral and lithic evidence from the site in order to create a chronology of events before tackling the age-old question of what it all means.