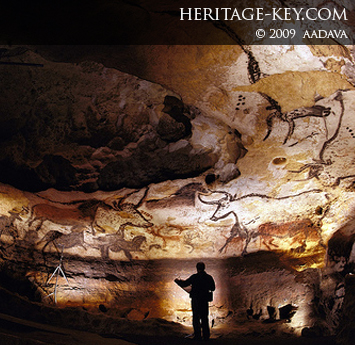

There’s no doubting the natural durability of cave and rock art – in many cases ancient paintings, carvings and sculptures have resisted tens of thousands of years of the withering effects of history and the elements to still be around to reveal their splendor today.

Yet, that’s not to say that their continued survival is guaranteed, particularly as many sites become more and more popular as tourist attractions and therefore increasingly subject to human wear and tear. Other examples simply don’t have the protection they need and are at the mercy of vandals and robbers, while some are threatened by modern development projects. Here we examine some of the ongoing efforts to preserve famous and important cave and rock art sites around the world.

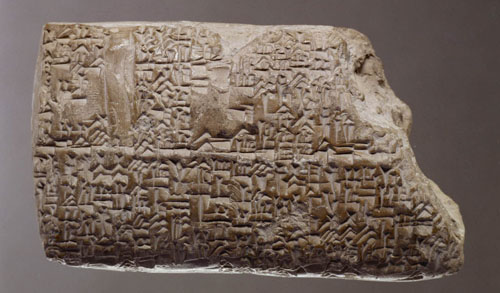

A Delicate Balance

Some cave paintings have survived the ravishes of millennia – while others have faded into dust – by the finest of margins. Lascaux Cave in France is one such example, and proof of the part human folly can play in undoing such a delicate balance.

After being discovered accidentally by teenagers in 1940, the spectacular, colourful images of giant bulls and horses at Lascaux quickly became a major tourist attraction, visited by up to 1,700 people a day. However, its caretakers realised that the tense equilibrium in the cave’s climate, which had kept the images intact for tens of thousands of years, was being interrupted by so many people passing through, and so it was closed in 1963. When it reopened, entry was strictly limited; after 1983 most visitors had to settle for Lascaux II, a modern facsimile.

After 2000 the cave became beset with a fungus, variously blamed on a new air conditioning system, the use of high-powered lights, and the presence of too many visitors. The fungus had to be painstakingly removed by hand; currently only a few scientific experts are allowed to work inside the cave, and just for a few days a month. There are fears that the images at Lascaux may have already been damaged beyond repair.

Other notable European sites have at least been able to learn from Lascaux’s mistakes. Altamira Cave in Spain, the so called “Sistine Chapel of the Paleolithic”, shut down in 1979 after tourist numbers of almost 180,000 a year endangered its existence. The attraction reopened in 1982 with a limit of 8,000 annual visitors; today that number has shrunk so drastically that the waiting list to enter the cave is three years long. A replica of part of the cave built nearby and opened in 2001 – and smaller replicas at the National Archaeological Museum of Spain in Madrid and the Deutsche Museum in Munich – are as close as most visitors can now hope to get to Altamira’s wonders.

Many other cave art sites in France, such as Niaux, Gargas and Pech Merle, have been forced by what happened at Lascaux to closely monitor their conditions too, not to mention drastically limit access. At Chauvet cave, custodians are taking no chances with its 30,000-years-old-plus paintings, discovered in 1994. Only researchers can enter, and that seems unlikely to change.

The Fight To Preserve African Rock Art

The example of Lascaux is sad, but at least its wonders – like all such European examples – have well organised experts looking out for them. Africa’s cave and rock art, including literally tens of thousands of examples, are hopelessly exposed. The few sites that are protected are in serious danger because the host countries can’t afford to enforce the laws or provide the necessary safeguards. Sun, wind, rain, termite trails and wasp nests are fading and eroding the thin pigment. Population growth, urban sprawl and the lure of tourism are taking a more rapid toll.

More alarming still is the deliberate damage done to many sites. Vandals and souvenir hunters ignorant of the art’s significance and value break parts off, scrape away the pigment and scratch their initials into millennia-old paintings and carvings. Amateur photographers throw water and other drinks on the art to make the colors more vivid, and sometimes even urinate on them. Some collectors steal whole chunks of images (by the hundreds in North African countries such as Morocco), while roving bands of armed guerrillas use them for target practice.

Experts and organizations have rallied round in a bid to try and protect some of these African treasures. Former president of the International Committee on Rock Art Jean Clottes, speaking to Time magazine, warned that they will “disappear forever in less than 50 years, if things continue at their current pace.”

The Getty trust runs the Southern African Rock Art Project, which aims to “arrange annual workshops and training courses to build capacity among staff in national parks and provincial nature reserves in all Southern African countries.” The Bradshaw Foundation too has been highly active in its endeavor to promote the preservation of African rock art.

Some progress has undoubtedly been made, with a number of important rock art sites in Africa now granted official UNESCO World Heritage Site status. Just one example of a successful preservation project is the Dabous Giraffes, two neolithic petroglyphs at the top of a lonely rocky outcrop in the middle of the Sahara desert in Niger which are among the finest examples of ancient rock art in the world. Under the Bradshaw Foundation, extensive work has been carried out involving making a mould of the carvings and then casting them in a resistant material.

The Battle Over Burrup

The Battle Over Burrup

Damage and threats to important ancient rock and cave art sites is not always strictly haphazard. In the case of the Burrup Peninsula in Australia, it’s practically state-sponsored.

The area, known as Murujuga by natives, contains one of the oldest and most extensive collections of aboriginal rock art anywhere in the world. Some of it is believed to have survived for 30,000 years or more (almost twice as long as Lascaux). Yet, claims have been made that since 1963, 24.4 percent of the rock art on Murujuga has been destroyed to make way for industrial development, and much more may go yet.

The preservation of the Murujuga monument has been called for since 1969; in 2002 the International Federation of Rock Art Organizations (IFRAO) commenced a campaign to preserve the remaining monuments. Bowing to this pressure, in 2007 the Australian federal government placed 99% of the islands in the Dampier archipelago, of which the Burrup is a part, on the National Heritage list – an impressive victory for the preservation campaigners. Yet, the remaining 1% is leased to Australia’s second biggest oil and gas producer, which is building a processing plant for its offshore natural gas reserve there and in the process will destroy or relocate thousands of examples of rock art. It’s a controversy that threatens to run and run.

A World Rock Art Museum?

Rock art expert Clottes, writing in the Getty Institute newsletter in 2006, singled out a number of sites around the world for praise in their efforts in preserving rock and cave art, yet making sure it remains accessible. They include Serra da Capivara National Park in northeastern Brazil, which is entirely fenced with guards monitoring its entrances, Kakadu National Park in northern Australia, some of which’s best sites are monitored by rangers, and Alta in northern Norway, where thousands of petroglyphs are within the bounds of a specially built museum.

He went on to call for better protection for rock art generally, to “eliminate or at least significantly diminish the impact of natural and human destructions.” He also called for the “safeguarding of knowledge of the art in case the worst should come to pass,” and the foundation of a World Rock Art Museum, which would function as a hi-tech centre for public viewing, a facility for training researchers, managers, rangers, and guides, a growing archive for the future and a fountain of information on how to collect and store data.

“Taken collectively,” Clottes concluded, “the above measures could advance preservation of rock art while raising the awareness of one of the most spectacular cultural achievements of humankind.”