It’s more than 4,000 years since people have stood around this grave-site unified by such an electrifying sense of awe and anticipation. Here in the tiny hamlet of Forteviot, nestled in a bend of the River Earn in the floor of a lush agricultural valley six miles southwest of Perth, the lid is about to be lifted on what archaeologists hope is a burial cist in one of the biggest Neolithic monuments in Scotland.

It’s more than 4,000 years since people have stood around this grave-site unified by such an electrifying sense of awe and anticipation. Here in the tiny hamlet of Forteviot, nestled in a bend of the River Earn in the floor of a lush agricultural valley six miles southwest of Perth, the lid is about to be lifted on what archaeologists hope is a burial cist in one of the biggest Neolithic monuments in Scotland.

We wait in chorus-line fashion, arrayed along the peak of the spoil-heap at the south edge of the trench cut into the ditch of a 250m-diameter henge. Around 50 archaeology undergraduates, lecturers and volunteer diggers are speculating on what’s underneath a four-tonne sandstone megalith which stunned site directors when it was unearthed in the 2008 three-week excavation season. In the intervening 12 months a lot of anticipation has built up around this stone. Believed to have been quarried locally, the massive five-sided angular block, measuring approximately two metres in diameter and 40 centimetres thick, appeared to have been packed-in stones. Initial theories supposed it to be a standing stone laid down on its side, potentially covering a cist burial cut into the henge.

Today, as a crane operator loops straps around its jutting corners and begins gingerly to raise it, excitable theories range from it being a manhole covering a subterranean supernatural tunnel, from which red light is going to shoot out, to there being a crisp packet wedged beneath it. The reality turns out to be beyond the greatest hopes of the archaeologists.

An Important Pictish Power-Base

First identified as cropmarks by aerial photography in the mid-1970s, the Neolithic ritual complex at Forteviot has been the focus of the SERF (Strathearn Environs and Royal Forteviot) research project, conducted by the Universities of Glasgow and Aberdeen, since 2006. Dr Kenneth Brophy and Prof Steve Driscoll, of Glasgow, and Dr Gordon Noble, of Aberdeen, are co-directors of the site, which has been documented in historical sources as having early Christian and significant medieval connotations as the place where Kenneth MacAlpin, first king of a unified Scotland, died at the “palace” of Forteviot.

Earliest mentions of Forteviot’s significance as an important Pictish power-base include the St Andrews Foundation Legend, 1140-53, which stated that a cross was erected by St Regulus and a basilica, dedicated to St Andrew, by Pictish king Hungus in the 8th or 9th century. It is also referred to in the Pictish king lists and the Chronicles of the Kings of Alba, which state that Cinead, son of Alpin (Kenneth MacAlpin), died “at the palacium of Forteviot” in 858 AD. Extensive documentary research has been carried out for the SERF project by Dr Nick Evans. The valley, bounded by ridges on the east and west, was marked by two impressive Pictish carved stone crosses, one of which, the Dupplin Cross, now stands a few miles along the valley floor in St Serf’s Church in nearby Dunning, while the other was destroyed.

While the excavation of a medieval cemetery and possible high-status enclosure at Forteviot, as well as digging at a hillfort at Green of Invermay and continuing search for evidence of the “palacium,” have been a key objective of the 2009 dig season, it is the lifting of the stone at the henge, situated in a corn field to the rear of Forteviot parish church, which has made national newspaper headlines.

It’s a Cist!

As the huge stone slab wobbles upwards suspended from the crane, with a couple of heart-stopping dunts as the straps slip from its corners, letting it clunk alarmingly back to the ground, the tension among the site directors is palpable. Prostrated on the ground, they peer under the stone, and the word flies out: there’s either a pit burial or a stone-lined cist underneath. As the capstone is laid face-down on the grass outside of the trench, the directors cluster around excitedly, and Dr Brophy yells over to the diggers craning to see from the spoil heap to confirm it’s a cist burial.

Investigation of the contents reveal incredible preservation of organic materials. Initial rumour of skeletal remains – almost unheard of in Scotland due to the acidic nature of the soil which disintegrates them – disappointingly turn out to be untrue. But there is what excavators describe as human residue – “white gunk,” to put it unscientifically. The burial appears to have been laid on a bed of quartz stones, of regular size, still gleaming white inside the cist with its beautiful, incredibly regular stone edging. On top of these has been a bed of birch-bark latticework, upon which the body was laid.

Within the burial there is a copper object, a copper dagger with a leather sheath, fragments of a wooden bowl, and a wooden and leather bag or container at what is believed to have been the end of the grave where the head was. At this end, the interior slab has carvings of axes on it, while the huge capstone itself has a unique carving of what seems to be a spiral plus an axe – something never before found in this part of Perthshire.

Removed the following day by specialist conservators from Historic Scotland, the organic and metal materials will be X-rayed and examined in the laboratory to find out more about them, while phosphate samples from the soil have been meticulously taken and will reveal much more detail not only about the interior of the grave, but also the wider landscape in which this burial, which has preliminarily been dated to 2200-2100 BC, was laid out.

Perthshire’s Agamemnon

As they work beneath a gazebo brought in to cover the cist, Dr Brophy and Dr Noble explain that the Early Bronze Age burial is around 500 years later than the henge monument, which measured 250 metres diameter, with a ditch six metres deep and two or three metres wide, encircled on the exterior by massive timber posts, possibly up to one metre thick, and a palisade, making it the largest enclosed space in Neolithic Scotland and on a par in terms of size and significance with Avebury, in southwest England. “In fact it would have been even more impressive than Avebury,” asserts Dr Brophy.

It’s later re-use seems to indicate that this location in prehistoric Forteviot was adapted for a different sort of purpose, while retaining its ritual significance over a long period of time. “A lot of effort has been taken to build this, which could equate to a high-status person being buried here, someone who has warranted this effort,” says Dr Noble. “It wouldn’t have been easy to move that four-tonne capstone.”

Dr Brophy adds: “They have some kind of high status. Whether that is negative or positive we can’t know, but something has picked them out for this.”

While there is no body, the real treasure of this grave, according to Dr Noble, is its impressive array of organic preservation. “It gives us insight into things other than those that normally survive, such as flint and metal objects, and will tell us a lot about what was going on in this period that we haven’t known before.”

But while the grave has been in the limelight this summer, with newspaper headline writers proclaiming the “hero” and “power-lord” as they gaze upon the face of Perthshire’s very own Agamemnon, Dr Brophy points out that the other work going on is no less vital to understanding this enormously complicated site and what made it so special to people over a span of 3,000 years.

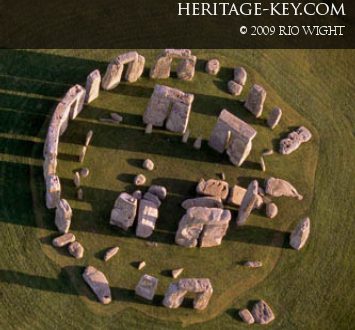

“The burial is really visual, it’s really easy to understand something about this type of archaeology, whereas some of the other things we are doing on site, because it’s cropmark archaeology, it’s a lot harder to understand unless you’re trained in archaeology to know what you’re seeing under the soil,” he says. “This monument would have dwarfed Stonehenge. There are pits inside it, and this summer we’re working on a mini-henge at one edge of it, trying to understand whether there were certain groups that had privileged access to certain areas. At some later stage the ditch was dramatically enlarged to perhaps 10 metres deep and three metres wide, then later again filled in with rubble you can see everywhere on the site. One of the objectives of this season is to understand these later phases, and the cist burial is part of that.”

Dr Noble concurs: “The cist burial is visually accessible to people, it gives a sense of what people were doing in the past. It’s the grave of an individual; that’s something most people can relate to, losing someone in their family.”

More Important Than Stonehenge?

Nobody who is on-site for the lifting of the stone underestimates its significance. The excitement as we take the tools back at the end of the day is palpable; we are all too aware that we’ve been part of an important find that will make the textbooks in years to come. “This is a once-in-a-career find,” one of the site supervisors acknowledges. “If this henge was built of stone, rather than earth and timber, it would be a place that pagans and hippies would worship – it would be more important than Stonehenge. Because it’s timber, which no longer exists, and a ditch and bank that you can no longer see, it’s hard to get people to understand how important and how massive a site this is.”