Iraq has had – shall we say – a colourful recent history. Wars with Iran, Kuwait, the US and the US again; insurrections, intifadas, genocide and rebellion have left a land which, while rich in natural resources, is one of the most shattered civilizations on the planet. Most would blame Saddam Hussein and his egotistical bigotry for Iraq’s current plight; others point the finger at the remnants of the Cold War, which left Iraq fighting an impossible proxy conflict with their Iranian neighbours – arming Saddam’s bloodthirsty Ba’athists in the process. Yet whatever your stance on the country’s twisted fate and economic desperation, there can be no doubting its wealth of history, heritage and millions of treasures, which unlock the secrets of the cradle of civilization. So what are Iraq’s Mesopotamian showpieces, and how have they been looked after by their modern descendents?

The National Museum, Baghdad

Baghdad’s foremost exhibitor of ancient treasures has been the focus of some guttural debate since the US-led coalition blasted their way into the capital. Before leaving for the dusty battlefields of the Middle East, American soldiers even issued a set of pictured playing cards, emblazoned with the images of Iraq’s greatest national treasures, to accustom them to both their heritage, and its importance.

Though the American army assured both concerned Iraqi citizens and the worldwide archaeological fraternity, widespread looting has taken place. Many stolen items have reportedly been sold on the black market to buyers in the Middle East and the subcontinent. The marines who first captured Baghdad have been highly criticised for doing nothing to stop such obvious acts of opportunism; they countered they had in fact been fired upon by Iraqi soldiers inside the building, using the museum as a sort of cultural shield. Donny George, the then-Director General of Iraq’s state board of antiquities, emphasised the professionalism of thieves, saying, “The people who came in here knew what they wanted. These were not random looters.” He presented glass-cutters to cement his case, and claimed near-perfect replica artefacts, almost identical to the real things, were left alone.

US Army officials, such as Lieutenant Colonel Eric Schwartz, maintained that forces had done their best to preserve the museum’s treasures. However the museum’s deputy director proved to be one of the army’s most vocal critics, arguing the Americans paid no attention whatsoever to the building during the first few days of Baghdad’s downfall: “The Americans were supposed to protect the museum. If they had just one tank and two soldiers nothing like this would have happened.” Since the first looting, the US deployed FBI agents in a bid to claw back some of the museum’s most vital objects. There was even an amnesty given to any Iraqis who brought back looted artefacts. And many items later resurfaced in places as far flung as Switzerland, Jordan and Japan. A few were even found being auctioned off on eBay. Yet many of the treasures are feared to have been lost forever, and, despite Iraqi guards being sent to keep a watchful eye over the closed museum’s remaining items, looting still continued for months after the first marine set foot in Baghdad on the 9th April, 2003.

But that’s not all: in the process of safeguarding the museum and searching for its lost treasures, Dr John Curtis, head of the ancient Near East department at the British Museum, claims troops and agents have disturbed vital archaeological material: “Archaeological sites are being destroyed in order to find these objects,” he argues. “In the process of that looting, very important archaeological evidence gets lost. And it’s this evidence that can tell us a great deal about the civilisation.” Dr Curtis argues the looting has created its own vicious circle – troops leave museum, museum gets looted; troops guard museum, loot disappears; troops search for artefacts, archaeological data is destroyed – and so on until, on the 23rd February 2009, the National Museum reopened to a fanfare of press and feverish optimism. Except that half its fabled possessions had vanished long into the desert sun. And, as British Museum director Neil MacGregor humbly observed, “A catastrophe has befallen the cultural heritage of Iraq.”

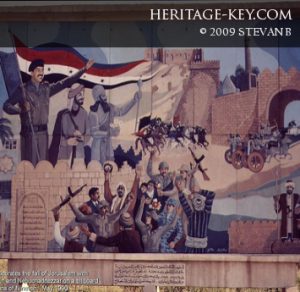

Some Iraqis still revere Saddam as a saviour who tried to bring prosperity to their ailing nation. They even believe his claims that he was the incarnation of the great Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar. Yet most of them would struggle to see the link, were they to see what he did to some of Nebuchadnezzar’s greatest achievements in his beloved Babylon. The list is almost comprehensive: in the bid to assume his supposed forefather’s identity, Saddam defiled the remains of almost everything Nebuchadnezzar has given his city. First up in his vaulted circus was the royal palace.

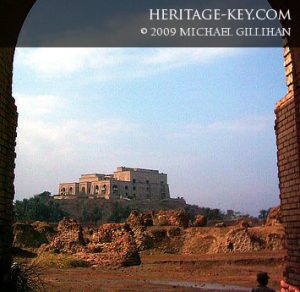

Nebuchadnezzar’s Babylonian seat was a fearsome, 600-room giant which overlooked his flagship metropolis. Never one for modesty, Nebuchadnezzar made his palace the embodiment of opulence; a towering colossus dripping in gold and grand idolatry. Every brick was inscribed with Nebuchadnezzar’s name, covering every corner with pomp and narcissism with phrases such as, ‘I am Nebuchadnezzar, the king of the world.’ Yet by the latter half of the 20th century the palace lay in ruins – a vital porthole through which to examine Babylon’s past. Eager to nurture his personality cult in the wake of the devastating Iran-Iraq War, Saddam built a modern replica of Nebuchadnezzar’s masterpiece – right on top of it. Archaeologists the world over were disgusted and outraged Saddam could desecrate such an important archaeological site; the bricks of Saddam’s new palace began to crumble after just a decade. Startlingly, in an effort to further emulate his forebear, Saddam embossed each of his new bricks with self-aggrandising motifs like, ‘This was built by Saddam Hussein, son of Nebuchadnezzar, to glorify Iraq.’ Not satisfied with one palace, Saddam later built an even bigger neighbouring complex in his own name.

The ancient ruins of the city itself, however, have come in for some of the harshest treatment over the past few decades. Similarly to his palace, Saddam spent billions reconstructing the city with yet more inscribed bricks, and right on top of the original ruins. Again, archaeological evidence had been destroyed, and the antiquarian world gasped in horror. Yet this time, the US Army could hardly spare a breath to gloat at the despot’s destruction. During the 2003 conflict, American soldiers constructed ‘Camp Alpha’ – which comprised, among other things, a helipad – directly on top of ancient Babylon.

US officials defended their actions at first, alleging they had saved the area from widespread looting and destruction with the camp. However, some months later Colonel John Coleman apologised for the camp, originally commissioned by General James T. Convoy. John Curtis fumed at the US Army’s supposed negligence, musing angrily: “the mess will take decades to sort out.” Substantial damage was also reported to the city’s famous Processional Way, leading to its ruins – and Saddam’s scale replica – of Nebuchadnezzar’s Ishtar Gate, one of the Seven Wonders of the World until replaced by the Lighthouse of Alexandria in the 6th century AD.

Elsewhere

Iraq’s wealth of historical monuments, ancient cities and artefacts is vast. To the north there are the ruins of the Assyrian capitals of Nineveh and Nimrud; to the south the great ancient city-states of Uruk and Ur, the latter of which is home to the imposing Great Ziggurat. Saddam again attempted a rebuild of this gargantuan step pyramid, yet the work remains incompleted. All of these sites are under constant threat from rockets, bombs and guerrilla warfare while the fledgling democracy of a ‘liberated’ Iraq still deals with hundreds of thousands of well-funded insurgents.

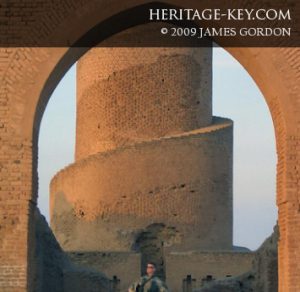

Yet one of the best-loved symbols of Iraq’s Islamic heritage – the Malwiya Minaret of the Great Mosque at Samarra – has taken a beating during the recent war. Samarra has been the site of some of the fiercest resistance to the American army, which led to their using the huge 9th century tower, a sand-hewn helter skelter of Abassid muscle, as an important look-out and sniper post. Inevitably it became the focus of a number of attacks, culminating in a bomb attack on the 1st April 2005 which blasted a hole in the minaret’s summit, sending plumes of brick and clay flowing down its spiral steps. It was a particularly odd attack as, despite the country’s crippling divisions between Sunni and Shi’ite Muslims, the mosque was a revered structure by both. If anything else, it shows that not even the historical sites beloved by both sides of the Iraqi and coalition spectrum are safe from the turgid conflict, which has gripped a true oilfield of Mesopotamian masterpieces. The archaeological world can do little for the treasures of wider Iraq, save for crossing their fingers every morning that another great monument hasn’t bitten the dust.