The oldest museum in the world, opens its doors to the public after a mammoth five-year revamp tomorrow. And the curators of Oxford’s famous Ashmolean will be hoping a new 61million building will help visitors enjoy and understand an envious collection of artefacts from the cradle of civilisation onwards.

The collection certainly has an esteemed pedigree, having been added to by archaeological greats like Arthur Evans, discoverer of the Palace of Knossos in Crete. So on the eve of one of its biggest days, what are the Ashmolean’s best objects?

1. The Jericho Skull

This skull, from 7,000 BC Jericho – one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities on the planet – embodies (or enheads) everything great about the mystery and macabre of early civilisation. This particular example was discovered in 1953, after which others have been found as far flung as the Ukraine. Were they the world’s first portraits?

The morbidity of its cowrie shell-inlaid eyes certainly hum with the dark fascination early cultures had for turning death into art. After all, this guy was walking, talking and living just the same as you and I once.

2. King Scorpion’s Macehead

The Ashmolean is home to the largest pre-Dynastic Egyptian collection outside Egypt itself, so no surprise the empire’s earliest leaders are accounted for well. This intricate piece is one of the era’s most important objects, effectively bringing into existence King Scorpion, for whom there is no other material evidence. The item’s ostensible use was as the bludgeoning attachment for a mace. Yet this one is so big it would probably need two men – kings or not – to cause a decent amount of damage.

Made from limestone, it was found in 1897/98 by Brit explorers James E. Quibell and Frederick W. Green in Hierakonopolis. Some experts believe that Scorpion, thought to have ruled around 3,200 BC, and his successor Narmer (owner of the renowned Narmer Palette) were one and the same; others that this was a gift from Narmer to Scorpion. It’d probably take you too long to gather enough evidence for yourself, so just enjoy the macehead. Oh, and did I mention this was the inspiration for the film The Scorpion King, starring The Rock? Avoid the temptation to smash it to pieces on your next visit.

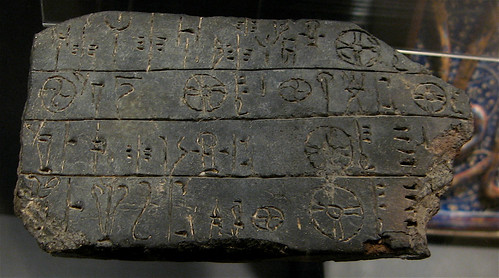

3. Mycenaean Linear B Tablets

A bit of a cheat picking multiple artefacts, but it’s my list so there. Not only could you spend all day staring at these pre-Hellenistic masterpieces, they’re also incredibly important in deciphering the Minoan culture and their Linear B language.

Discovered by Arthur Evans on one of his many missions to Crete at the turn of the 20th century, these formed the basis for his long-running efforts to decode the earliest writing of an almost mythical Bronze Age nation, which would go on to spawn one of the world’s greatest cultures.

4. Alfred Jewel

This amazing 9th century AD Saxon ornament was first discovered in 1693, just ten years after the Ashmolean was built. Thus it is one of the museum’s longest-standing objects, and still one of its most spectacular. It is fashioned from gold with quartz crystal and the cloisonn enamel image of a man, and was found in the Somerset town of North Petherton, the site of a once-great monastery founded by King Arthur.

The ornamentis inscribed with the words ‘Alfred Ordered Me Made’ – so there’s no mistaking who it belongs to. Bit better than the labels sewn into your school clothes, eh?

5. Fired Clay Hippopotamus

It may look innocuous enough, but this small hippo is one of the Ashmolean’s showcase pre-Dynastic Egyptian artefacts. Though they may not have carried divine qualities at the time (around 3,500 BC) hippos went on to become the hippo fertility goddess Taweret – ‘The Great One’ – in later dynasties.

They would definitely have been respected, mind – they’re still the deadliest animal in Africa today. Found in Hu, Upper Egypt, this model was found at the end of a grave; implying hippos helped early Egyptians reach their version of the afterlife over 5,000 years ago.