The media preview for Fakes and Forgeries: Yesterday and Today was held today. It will be opening at the Royal Ontario Museum, in Toronto Canada, this Saturday. It’s a much smaller exhibition than the King Tut and Dead Sea Scrolls shows that have hit Toronto recently, and will potentially be dwarved by the very large China show that may or may not include the Terracotta Warriors this June. But Fakes and Forgeries offers some strong lessons about the world of fakes and the experts who try to out them.

The media preview for Fakes and Forgeries: Yesterday and Today was held today. It will be opening at the Royal Ontario Museum, in Toronto Canada, this Saturday. It’s a much smaller exhibition than the King Tut and Dead Sea Scrolls shows that have hit Toronto recently, and will potentially be dwarved by the very large China show that may or may not include the Terracotta Warriors this June. But Fakes and Forgeries offers some strong lessons about the world of fakes and the experts who try to out them.

How the ancient section of the exhibit works is that there are stations for China, Egypt and Mexico as well as a catch-all table that includes Greek wares.

You see fake artefacts and real ones. After being given some background information you pick out which ones that are fakes and which are real. Opening a slot at the bottom you find your answer.

I knew some of the answers in advance since I had access to a media kit.However -I have to admit -I didnt do that much better than 50:50 with the remaining ones. But, I was far from the only one who got fooled by the fakes.

I spent some time at the Zapotec tables and watched a few guests guess that the urn in the shape of Cocijo, the Zapotec god of rain, was real (it isnt).

Which brings me to the first lesson that this exhibit teaches us-

Even a Museum Full of Experts Cannot Always Spot Fakes

We like to think that with a PhD, and lots of drive, we can always spot fake artefacts with our bare eyes. We also like to think that a museum full of experts can never be wrong. But that is simply not the case.

We like to think that with a PhD, and lots of drive, we can always spot fake artefacts with our bare eyes. We also like to think that a museum full of experts can never be wrong. But that is simply not the case.

The experts had quite a bit of trouble with the Zapotec artefacts themselves. In case you dont know know about these people, the Zapotec culture dates from 500 BC until present andis based in Mexico.

Exhibit curator Paul Denis told Heritage Key in an interview a month back that out of the hundreds of ancient Zapotec artefacts the Royal Ontario Museum has, about half of them are fake.

And no, those Zapotec artefacts were not donated to the museum by unwary tourists. Charles Trick Currelly, an archaeologist and one of the founders of the museum, purchased many of them on a trip to Mexico.

He thought that he could spot the fakes, but he was wrong.

Its just reaching too far, Denis said.

It took some time for the museum to out the artefacts. In fact it wasnt until the advent of Thermoluminescence (TL) dating that they could tell for sure which were which.

Lesson Two While Some Forgers are Brilliant Others are Comically Bad

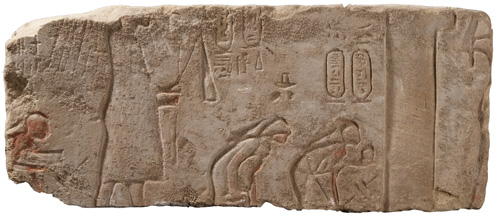

Take a look at the picture of the pharaoh below. This clumsy fake is so bad its hard to imagine it passing muster at a flea market. A crude and contrived representation the museum said in their literature Ill sure say!

Then there is a rathercomic attempt to imitate a Zhou Period period belt hook. The forger created an ornately decorated hook that was nearly a meter long. Unless the Ancient Chinese had some massive obesity problems it would have been of no use.

On another funny (but not ancient) note a 1954 attempt to fake bank notes in Canada was foiled, in part, because the forgers couldnt get the Queens hair style quite right. Its not clear if the forger was ever brought to court but, if he or she was, it must have been quite a trial.

Now, Heres the one Serious Criticism That I Have

There is a third lesson which I would have liked to have seen. That is that the most impressive artefacts in a collection, the ones that appear in history books and as the centrepiece of major exhibits, can just as easily be faked. Prestige offers no immunity. The high-profile speculation around the bust of Hatshepsut and, especially, the Nefertiti bust, have proved how difficult it really is to tell replica artefacts from the real thing.

There is a third lesson which I would have liked to have seen. That is that the most impressive artefacts in a collection, the ones that appear in history books and as the centrepiece of major exhibits, can just as easily be faked. Prestige offers no immunity. The high-profile speculation around the bust of Hatshepsut and, especially, the Nefertiti bust, have proved how difficult it really is to tell replica artefacts from the real thing.

About 10 years back there was a major controversy when it was suggested that Our Lady of Sports an iconic Minoan statue of a female in theRoyal Ontario Museum’s collection is a fake. Again, it was acquired on Crete by Charles Currelly whom, as youve already seen, wasnt exactly the best in the world when it came to spotting fakes.

After some media buzz about whether the artefact is real, the statue was pulled. The conclusion eventually reached is that it is indeed fake. It seems that some of the workers with Sir Arthur Evans were doing a brisk side business faking artefacts.

It was a bad hit for the museum.

The statue had been on display in Toronto for nearly 70 years. Evans himself had written about it. He even featured a picture of it at a London exhibition at the Royal Academy of Art in the 1930s.

I remember going to the ROM when I was a teenager and staring at the statue it was simply beautiful a great example of Minoan art (or so I thought). I was disappointed when I heard that it likely was not real and I developed just a little bit more caution when it came to looking at artefacts in a museum collection.

So today, when I went to Fakes and Forgeries, I was a bit disappointed that the statue was not part of the exhibit. Speaking to Dr. Dan Rahimi, Vice President for Gallery Development, he said that the exhibit will be travelling after its Toronto showing and that the fake Minoan statue is too fragile to bring along.

It seems the forgers even got the fragility right…not bad for a fake.

What do you think – can replicas be as good, and even better (in preservation terms) than the real thing? Tell us what you think in our special HK survey, and see what others have to say about the issue.