Dr. David Silverman is delighted at the thought that visitors to Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs, one of two King Tut exhibitions touring North America right now, would come away as I did – with an itching interest in Akhenaten, who was almost certainly King Tuts father.

Dr. David Silverman is delighted at the thought that visitors to Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs, one of two King Tut exhibitions touring North America right now, would come away as I did – with an itching interest in Akhenaten, who was almost certainly King Tuts father.

Hes also enthused at the idea that viewing the vast exhibition at the Discovery Time Square Exposition, with 130 significant objects from King Tuts tomb and the 100 years preceding the boy kings life, will spur people to go take a look at King Tuts funerary urns up at the Met, or the other fascinating Ancient Egyptian things on display at the Brooklyn Museum.

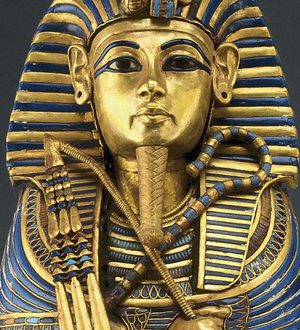

What he’s less enthused about, however, is the fact that people keep on complaining about the conspicuously absent golden death mask, and the almost-identical golden image that is used in all the posters. Somewhat wearily, he speaks to Heritage Key about the controversies surrounding the exhibition of the year in New York.

Pulling in the Non-museum Crowd

What Silverman would really love is to attract people who never normally go to museums, but are spurred into action by the broad appeal of Tutankhamun. He knows very well how powerful that appeal is, having curated the U.S. leg of the blockbusting Treasures of Tutankhamun exhibition in 1977.

I want to approach the audience that doesnt come to museums, said Dr. Silverman. He explained that, so far, audience surveys for the two exhibitions (the other one is Tutankhamun The Golden King & the Great Pharaohs), both arranged by Arts & Entertainment International in conjunction with National Geographic, show that around half of those visiting are not the museum-going sort at all.

I want to approach the audience that doesnt come to museums, said Dr. Silverman. He explained that, so far, audience surveys for the two exhibitions (the other one is Tutankhamun The Golden King & the Great Pharaohs), both arranged by Arts & Entertainment International in conjunction with National Geographic, show that around half of those visiting are not the museum-going sort at all.

Part of the success in pulling the non-museum crowd may well be about the fact that the exhibition is housed in the glitzy commercial space of the Discovery Exposition, which opened last year in the old New York Times building that gave the square its name years ago, where New York is at its trashiest and most overpriced. The space is huge, which gives a marvelous opportunity to spread out the material into a true adventure of discovery as you walk through a maze of room after room. It also has very little of the Shhh! feel of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, forty blocks away on the edge of Central Park.

Not that the exhibition isnt an awe-inspiring show its just that it doesnt feel like the grown-ups have taken all the fun out of it. Its an opportunity to approach a museum-like exhibition thats not in a museum, Silverman explained. That, in turn, he hopes, makes it an attractive jumping off point for delving deeper into whats on show to the public in other, more initially intimidating institutions.

New York’s Other Exhibition Venue

Still, the location of this exhibition has stirred some controversy, not least by Zahi Hawass, the outspoken Secretary General of the Supreme Council of Antiquities in Egypt and minder of King Tuts treasures, who, at the press preview of Golden Age exhibition last week, staged a humiliating little dig at his partners in the exhibitions by demanding an explanation, as if he didnt already know, as to why the exhibition was not on show at the Met (which housed the 1977 King Tut show).

The answer, of course, was money. The Met declined to meet Hawasss ambitious demands for profit-sharing (he is fervent about raising money for the huge new Grand Egyptian Museum at Giza, and rightly so).

Silverman wishes people would focus on the exhibition more than questions of venue. Im a very practical person, Silverman said. I think about the amount of space, the number of artifacts, and what will allow people to see and read as much as possible. The bigger the space, the more chances there are to do that. In 1979, the King Tut exhibition in Seattle ended up in a convention center, not the Art Museum, and that worked out just fine, he points out.

The Fuss Over the Absent Death Mask

Silverman is also dismayed by the attention being given to the absence of King Tuts famous golden mask. Although I understand that the mask has now been declared too delicate to travel, and that there is much to be said for encouraging people to visit Egypt if they really want to experience the full range of Ancient Egyptian treasures, I asked Silverman why he didnt at least put in a little explanation about what the mask was and why it wasnt there.

When I write about an exhibition, I write about whats in the exhibition, he explained, rather wearily. In any exhibition, theres always something you cant have, he continued, citing the wooden torso he used on the cover of his first book, Masterpieces of Tutankhamun, as something that can no longer travel and is a wonderful piece you cant see without going to Egypt.

Silverman suggests that anybody who knows the material would know the image being used on all the posters for the current exhibitions was from a smaller coffinette holding King Tuts liver, and not mistake it for the golden mask (I have to say, I disagree here; even I was fooled.) Besides, he said, in the 1970s, the Chicago Field Museum used a reversed imaged of the coffinette to advertise King Tut. Nobody asked: Why did they use that, he protested.

Next up: Denver

All in all, King Tut is bound to produce a range of strong emotions, which is, of course, part of his appeal. I simply allow the artifacts to tell the story, explained Silverman, adding that the items were chosen by the Supreme Council of Antiquities before he came on board in any case. He realized there was a great opportunity, through Tutankhamun and The Golden Age of the Pharaohs, to talk about the most important part of the 18th Dynasty of Ancient Egypt, because the items included the Boy King and about 100 years before his reign, including great grandmothers.

So King Tut is back and this time hes brought his family! he enthused. The other exhibition, Tutankhamun The Golden King and the Great Pharaohs, which is just moving from Toronto to Denver, gives a broader idea of what life was like in Ancient Egypt. What was palace life like, what was the religion? he said. That exhibition also focuses on the myriad uses of Egyptian gold the ready supply of which is what really shaped and powered the civilization, in many ways. Not a bad way to introduce the general public to the wonder of 2,500 years of history.

If you’re not satisfied by the coffinettes and want to see King Tut’s golden death mask in full 3-D glory, visit King Tut Virtual. There are no crowds, no entry fee, and no embarrassing comments about how you should be at the Met!