Virtual Qumran designer Dr. Robert Cargill is at the forefront of a rapidly evolving discipline. He uses virtual reality as a tool to conduct archaeological research on Qumran, the site where the Dead Sea Scrolls were found in caves. An archaeologist by training, Cargill has taken it upon himself to learn how to create a virtual reality model of a site, a skill most archaeologists haven’t picked up – yet. He generously took some time off from his busy schedule to talk to me about Virtual Qumran and how virtual reality is changing archaeology.

Model Behaviour

Archaeologists, Dr. Cargill points out, have been making models of their sites before computers were even used. Whether sketching them on pen and paper, or using a simple computer illustration system, modelling has long been popular.

The reason is that it allows non-specialists, who don’t understand the minutiae of an archaeological report, the chance to grasp what a site looked like in antiquity.

The problem is that archaeologists will often disagree on the details of how a site looked. Cargill said that what used to happen is that an archaeologist would create a model and then, “another archaeologist would come along and say no, no, no, he’s misinterpreting or she’s misinterpreting this wall. That’s not what it looked like.”

“So they’ll offer a reconstruction but they’ll do it in a different media with a different angle with a different style etc, etc,” he said.

“So what you end up in archaeology with is two different looks in two different publications and there’s really no way to test the two.”

Virtual Reality Solution

A virtual reality models solves this problem. It allows archaeologists to test out different ideas as to what a site looked like.

Archaeologists will usually agree on some aspects of a reconstruction. For the parts that they disagree on they can try out the various ideas. Dr. Cargill refers to the different versions of an archaeological site as “data switches.”

“What we can do in virtual reality is I can create a series of data switches,” says Cargill. “Okay, let’s reconstruct this wall the way archaeologist A said (then) let’s go here on this switch and see how archaeologist B says.”

“Once you put (the interpretation) into greater context (you realize) that certain reconstructions don’t work”

Sometimes flying around in Virtual Reality isn’t even necessary. If architectural information that defies the laws of physics is entered into a model, a re-creation cannot even be done.

“The span of this is too far – it would collapse in reality, things like that.”

Qumran

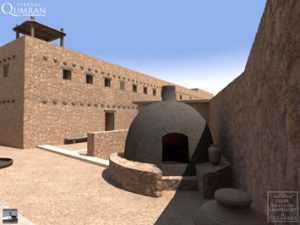

Dr. Cargill, and other members of his team, have done this type of research first-hand in creating Virtual Qumran.

Qumran was first excavated nearly 50 years ago. The archaeologist who first unearthed it, Roland de Vaux, claimed that the site was inhabited by a monastic group called the Essenes. He believed that they followed a strict interpretation of Jewish laws and tradition and wrote the Dead Sea Scrolls.

But, in early 2005, just three weeks into their modelling work, Dr. Cargill’s team realized that de Vaux’s theory couldn’t possibly be true.

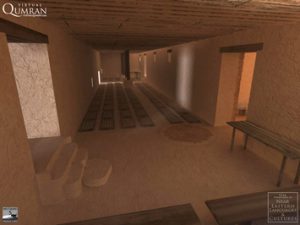

“Certain buildings, the scriptorium (locus 30), the dining room (locus 77), appeared to be additions to a pre-existing structure,” he said. “That isn’t consistent with the theory that those buildings always supported Qumran from the beginning.”

“That’s when we said, ah man maybe we better relook at this… that’s when it became a research project instead of a reconstruction just to show someone else’s theory.”

As the reconstruction went on, new data came in, including a preliminary report from recent Qumran excavators Peleg and Megan. This was incorporated into the model.

Dr. Cargill agrees with the two excavators that the site started off as a military outpost and transitioned to civilian use in the first century B.C. However he disagrees with the idea that Qumran had nothing to do with the writing of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

He was careful to praise the work of Peleg and Megan saying that they are making “great contributions to the archaeology of Qumran,” and that many of their ideas appear to be correct according to the reconstruction.

Computer Says… Scrolls

The Qumran model indicates that civilians moved in after the Hasmonean military left in the first century B.C. They altered the complex, adding rooms that weakened the defensive nature of the site.

“Somebody added these rooms on and they did so in a non-military fashion. It was also a communal fashion,” Dr. Cargill said. “All of the rooms added to Qumran are long rooms, big rooms, not like little rooms.”

Dr. Cargill believes, based off of the original data and its reconstruction, that the site supported a small population, no more than 70 people. They engaged in a number of “self-supporting” tasks including animal husbandry, pottery making and most importantly, writing.

Cargill points out that Qumran had multiple inkwells. “Somebody was writing something at Qumran,” he says – and he thinks this included some of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

He theorizes that the civilians at Qumran did write and copy scrolls. Also, when new people arrived at the settlement they brought their scrolls with them. Over the years these would have piled up into the 900 scrolls we have today.

In 68 AD the Roman army arrived at Qumran. Cargill believes that the inhabitants, getting ready to flee from them, couldn’t take their scrolls with them and decided to put them in caves.

As further evidence Cargill points out that many of the caves, where the scrolls were found, “cannot be gotten through without going through the residence of Qumran.”

Also, the virtual model refutes the idea that Qumran’s main purpose was pottery production. Cargill said that some of the cisterns that Peleg and Megan believe were used to transport potters clay, were actually used for water storage.

There is other evidence, not related to the model, that Cargill cites to support his theory. The Dead Sea Scrolls content is “cohesive” with a similar worldview (ie, the belief in a messianic apocalypse), which reflects the idea that a group of people with similar ideas put them together. He also mentions evidence that the ink from some of the scrolls, came from the Dead Sea area.

New World Model

The method that Cargill has used with Virtual Qumran is unique in that “the excavator is the illustrator.” He says, “One of the things that I’m proud of is that I’ve offered the world, I’ve offered whoever’s interested, a new methodology of doing virtual reconstruction.”

In the past, virtual reconstructions of ancient sites (at least those created for research purposes) have tended to work like this:

The archaeologist, who usually lacks training in computer sciences, will go and excavate a site, recording their findings on CAD, Excel, and good old fashioned pen and paper. When they go to create a virtual reconstruction they will take their work back to a university and hire a technologist to recreate the site. After some back and forth between the archaeologist and the technician a virtual site is created.

“Wouldn’t it be neat if archaeologists knew how to digitally model?” Cargill said. “Instead of recording their data on paper maybe they can record it in a database that allows you to capture not only numbers and values and letter, but also geometry?”

He said that the technology is not as hard to learn as you might think. “I’ve put together a methodology that says excavators can learn how to do this too… It will require some technology training,” he said. “But it shouldn’t require any more so than learning CAD, than learning Adobe Photoshop or learning a new version of some other piece of software.”

Dr. Cargill uses Presagis Creator, which he describes as essentially “a database where you can store text and numbers”, although Maya is also a popular program among archaeological modellers. Google has also recently released Google SketchUp, a free program which he believes will “come to dominate.” With that platform not only can you create models but you can easily put them into Google Earth.

Cargill paints a picture of a new world order for archaeologists, in which virtual reconstructions become a key tool to illustrate, and put to the test, the theories of archaeologists. Virtual Qumran certainly provides an excellent model.